This circa-1864 structure, "one of a few surviving frame houses in Harlem which date from the period in the city's history when Harlem was still a rural village", is said to feature one of New York's earliest mansard roofs, predating by a few years "the mansard mania of 1868 to 1873 [which] swept over New York with a peculiar incandescence, but then went out like a guttering candle." (The roof is referred to as a mansard by many architectural sources more knowledgeable than me, but I don't think that is an accurate description, as the roof does not appear to be hipped.) You can see a couple of old photos of this building, as well as one interior shot, here.

This is the home of Homebase, an organization that works to "[prevent] homelessness throughout Manhattan by helping clients resolve any immediate housing crises that placed them at risk of becoming homeless."

Painted by — no surprise — the Royal Kingbee, whose relationship with the drug store chain now clearly transcends the bounds of the Bronx.

I believe this was once an ad for Dr. Tutt's Liver Pills. Why Dr. Tutt's? Because "constipation is a crime against nature . . . Dr. Tutt's Liver Pills is the remedy . . . Get a box and see how it feels to have your liver and bowels resume their health-giving natural functions."

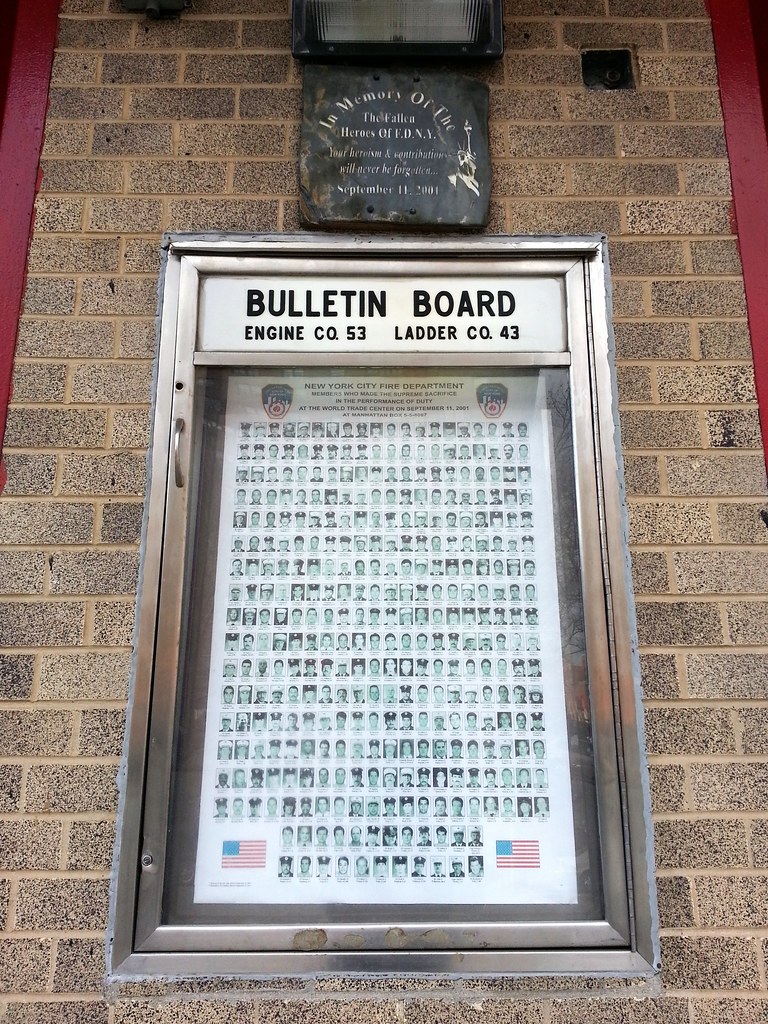

Here's the second part of it. Each of the component pieces of this memorial is identical or at least very similar to something we've seen before, but I think the combination of them all warrants inclusion in the official list as a unique memorial.

Heading south into Metro-North's Park Avenue railroad tunnel is what I believe is a ballast tamper (I'm pretty sure that blue blur on the side reads "Tamper"), followed by some tools and supplies being pushed by a clown car.

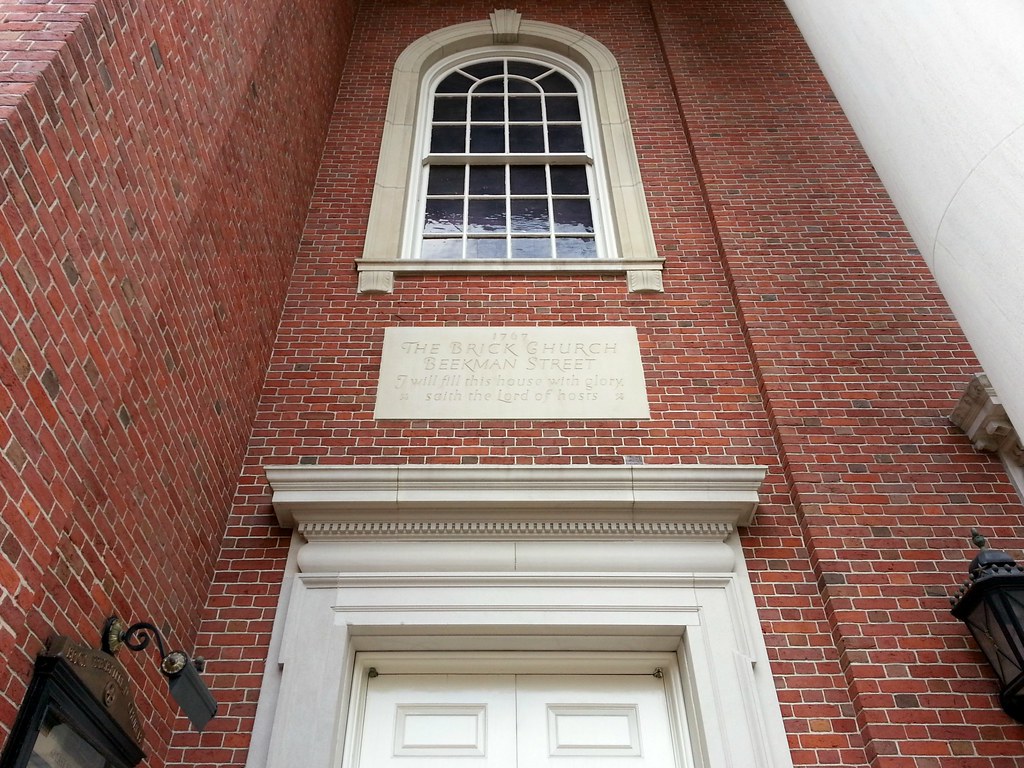

As the text inscribed above the doorway indicates, the first incarnation of this Upper East Side church was built around 1767 down on Beekman Street. That structure served the congregation until 1856, with the exception of several years during the Revolutionary War when the British used it briefly as a prison and then turned it into a hospital. The second Brick Church opened in 1858 on Fifth Avenue and 37th Street, and the present building was dedicated here at Park Avenue and 91st Street in 1940.

Tucked away in a little indentation in the facade is a stone that reads "PVB Livingsto 1767". It is apparently a replica of a foundation stone from the original church building; Peter Van Brugh Livingston was an elder of the congregation who, according to the church, "was instrumental in securing" a perpetual lease for the site on Beekman Street, which a 1909 NY Times article described as "about the finest piece of property the city owned . . . that very choice bit of real estate bounded to-day by Nassau and Beekman Streets and Park Row". (Full disclosure: the Times's headquarters occupied the same site for almost half a century after the church left in 1856.) A history of the church published in 1909, whose release prompted the aforementioned Times article, offers a different opinion, however, saying that "the property in question had in 1765 comparatively little value. . . . [The land] was on the extreme northern edge of the city."

I saw several buildings on Park Avenue today with similar lights; the idea is that a doorman will turn on the bulb when a resident of his building needs a cab at night. (The security camera above the light is unrelated to the taxi-signaling efforts.)

According to a 2003 NY Times article entitled "Futile Beacons of a Bygone Age":

Hundreds of these little lights can still be found in the city's upscale neighborhoods. . . .

An informal poll of more than a dozen doormen on the Upper East and West Sides suggests that the system has long stopped working.

"They just drive on by," said a doorman at a building on 79th Street near York Avenue. "We only do it to make the residents happy." . . .

Andrew Alpern, the author of "Luxury Apartment Houses of Manhattan: An Illustrated History," suggests that these urban fireflies date to the 1940's, or more specifically World War II. As men went off to war, a dearth of doormen ensued.

"Without a doorman to hail the cab for you," Mr. Alpern said, "they may have started putting in these lights so that the elevator man could flip on the taxi light. And that would be the extent of his trying to get a cab for you."

Parked outside the Dutch Girl Cleaners at 1082 Park Avenue, a.k.a. "Sicily in terra cotta"