This is apparently Staten Island's only Polish restaurant.

That's JFK Airport's air traffic control tower depicted on the sign. JFK is more than 20 miles away by car, so I was surprised to see a restaurant here named after one of its terminals. But it turns out that LOT, Poland's national airline, operates out of JFK's Terminal 1, so I'd imagine that's where the name came from. (O'Hare in Chicago is LOT's only other US destination.)

At the dead end of Quincy Avenue, I followed a little trace of a trail a few hundred feet into the woods, and this is where it led me.

The Vietnam Wall Experience (a.k.a. the Dignity Memorial Vietnam Wall) is a traveling three-quarter-scale model of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. It's currently "temporarily retired" at Fort Benning, Georgia, but prior to that it was exhibited all over the country. It came to Staten Island in May 2003, and it seems that a time capsule was left here to commemorate its visit. I'm not sure what the capsule contains, but perhaps, like a capsule that was buried in Tucson after the wall visited in 2005, it's filled with "memorabilia that was left at the wall".

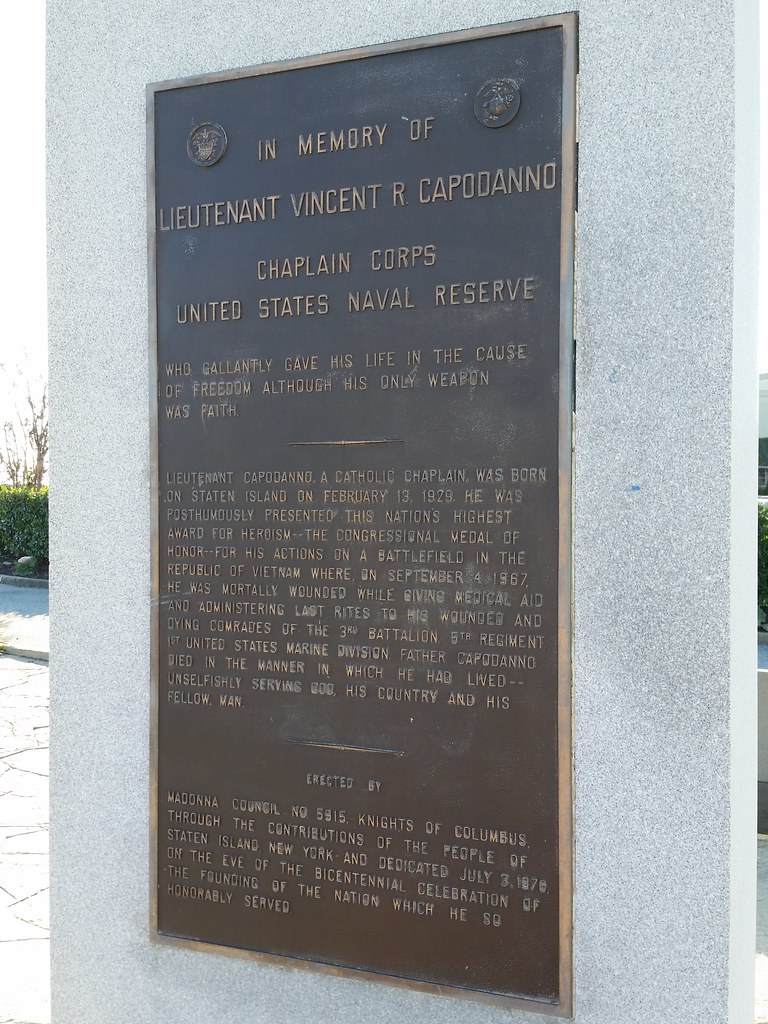

This memorial honoring Father Capodanno stands next to the Vietnam Wall Experience time capsule on Father Capodanno Boulevard. Father Cap was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for

conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Chaplain of the 3d Battalion, in connection with operations against enemy forces. In response to reports that the 2d Platoon of M Company was in danger of being overrun by a massed enemy assaulting force, Lt. Capodanno left the relative safety of the company command post and ran through an open area raked with fire, directly to the beleaguered platoon. Disregarding the intense enemy small-arms, automatic-weapons, and mortar fire, he moved about the battlefield administering last rites to the dying and giving medical aid to the wounded. When an exploding mortar round inflicted painful multiple wounds to his arms and legs, and severed a portion of his right hand, he steadfastly refused all medical aid. Instead, he directed the corpsmen to help their wounded comrades and, with calm vigor, continued to move about the battlefield as he provided encouragement by voice and example to the valiant marines. Upon encountering a wounded corpsman in the direct line of fire of an enemy machine gunner positioned approximately 15 yards away, Lt. Capodanno rushed a daring attempt to aid and assist the mortally wounded corpsman. At that instant, only inches from his goal, he was struck down by a burst of machine gun fire. By his heroic conduct on the battlefield, and his inspiring example, Lt. Capodanno upheld the finest traditions of the U.S. Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life in the cause of freedom.

Looks like this middle section of the roof has long been collecting water — and presumably some windblown organic matter as well. Perhaps the phragmites seeds were also blown in on the wind, or maybe they were carried here by birds looking to take a nice bath in the accumulated roof water.

In Loving Memory of Anthony D. Paino

What's a Bluebelt?

The Staten Island Bluebelt is an award winning, ecologically sound and cost-effective stormwater management for approximately one third of Staten Island’s land area. The program preserves natural drainage corridors, called Bluebelts, including streams, ponds, and other wetland areas. Preservation of these wetland systems allows them to perform their functions of conveying, storing, and filtering stormwater. In addition, the Bluebelts provide important community open spaces and diverse wildlife habitats. The Bluebelt program saves tens of millions of dollars in infrastructure costs when compared to providing conventional storm sewers for the same land area. This program demonstrates how wetland preservation can be economically prudent and environmentally responsible.The Adopt-A-Bluebelt program "offers local community groups, companies and individuals an opportunity to enhance Staten Island's open spaces by acting as Sponsors who adopt parts of the Bluebelt." Many sections of Bluebelt have been adopted by families in honor of lost loved ones, and since much Bluebelt land is swampy and inaccessible, the roadside Adopt-A-Bluebelt memorials, while having nothing to do with stormwater management, are often the Bluebelts' most publicly visible features.

This appears to be another roadside memorial, presumably for a child. Up above the bear on the pole are a cross and a package of toy cars, as well as a bar code label that reads "BLUE BEAR" (close-up).

Adjacent to the South Beach Psychiatric Center, Ocean Breeze Park is well within the range of the Staten Island turkeys. (I took this photo right at the edge of the park the other day.) I also saw numerous turkey tracks on the park's dirt paths today.

On July 21, 2010, the day ground was broken on this massive, 135,000-square-foot track and field facility in Ocean Breeze Park that has ended up costing $93 million, the city put out a press release saying "the $70 million . . . Ocean Breeze Track and Field Complex is anticipated to complete its construction by the end of 2012." Whoops. But it will open one of these days, really! (Also, "is anticipated to complete its construction" is a bizarre phrase that almost seems like it was presciently designed to hold no one but the facility itself accountable when construction inevitably dragged on longer than "anticipated".)

Fun fact: There was a period of time during the fall of 2012 when the building's acoustic baffling panels hadn't yet been enclosed inside the structure and were driving neighbors crazy with the loud, strange sounds they made in certain wind conditions: "high celestial harmonies . . . like [a] battalion of crickets armed with sopranino recorders . . . like 100,000 people with unlimited air in their lungs blowing through Coke bottles".

at the South Beach Psychiatric Center. When I was looking up what a group of turkeys is called, I discovered some great names, many archaic or obsolete, for groups of other types of birds as well, including:

- A bouquet of pheasants

- A charm of finches

- A deceit of lapwings

- A descent of woodpeckers

- An exaltation of larks

- A murmuration of starlings

- A murder of crows

- An ostentation of peacocks

- A parliament of owls

- A siege of herons

- An unkindness of ravens

This recreational pier, "outfitted with fishing rod holders, bait cleaning tables and customized fish cleaning stations", opened in 2003.

The centerpiece of the Midland Beach entrance plaza, this sculpture is teeming with marine life. If you look closely, you can find "striped bass, fluke, flounder, lobsters, crabs, sea stars, and mud snails", not to mention a squid and an octopus. (And speaking of life, you can see the double-helix structure of DNA evoked by the wavy bench canopies and pathway railings behind the sculpture.) Not surprisingly, work began on this animal extravaganza during Henry Stern's tenure as parks commissioner.

The signs outside the Little House in the Gully, which had been pushing for a state buyout of the Bowl (this low-lying section of Ocean Breeze that was hammered by Hurricane Sandy), have been updated to express gratitude for the state's buyout offer. You can see two more of the new signs here.

The treed island at left is Hoffman Island and the smaller (and more distant) one at right, which you might need to zoom in to see, is Swinburne Island. (The built-up land at far left is part of Coney Island.)

Construction on these two artificial islands began in the mid-1860s. They were built to serve as quarantines after two previous such facilities on Staten Island were burned down by angry neighbors. Isolated from the rest of the city, the islands proved to be more palatable locations for detaining the sick.

The Swinburne quarantine closed in 1928 and the island has been abandoned ever since, except for a stint as a control center for underwater mines during World War II. Starting in 1931, Hoffman Island saw a few different uses: it was home to a parrot quarantine, a picnic ground, and a merchant marine training school before being abandoned in 1947. The islands have been part of Gateway National Recreation Area since 1972, although they are off limits to the public.

A response to Hurricane Sandy: "You Can Take Our Homes But You Can't Take Our Hearts"

Named after a graffiti tag seen on subway cars around the time of its creation in 1982, this colossal piece by Bill Barrett can be found on the steps of New Dorp High School. According to an NY Times art critic, it is "one of the most successful public sculptures in the city", and it is supposedly popular enough at the school that its likeness was once put on the football team's helmets.

Our Lady of Lourdes is, I would have to imagine, the only Catholic church in NYC that is owned by the city, and certainly the only one that stands inside a public park. How did the Parks Department come to be the landlord of an active house of worship? Well...

The church was erected here in New Dorp Beach around 1924 to serve the area's bungalow-dwelling population. Between 1958 and 1962, to make way for a shorefront parkway that Robert Moses wanted to build, the city used eminent domain to acquire all the properties in New Dorp Beach east of Cedar Grove Avenue (map). With the exception of the church, all the buildings that stood there — including dozens of bungalows and an old hospital — were demolished, only to have the parkway plan never come to fruition (aerial photos: 1951, 2012). The condemned land is now city parkland, leaving Our Lady of Lourdes in the odd position of having to rent its own building back from the city, and leaving the city in the odd position of owning an active church.

Hurricane Sandy's massive storm tide ravaged many nearby houses in New Dorp Beach, but the church's chapel, standing well above street level at the top of the steps, was untouched by the rising waters. The ground floor, however, was ruined, forcing the city-funded senior center located there to close. The center is still shuttered today and will be for some time, but the city now has plans in the works for its reconstruction.

This is the former site of the Cedar Grove Beach Club, a collection of cottages mostly built between 1907 and 1924 that was Staten Island's final beach bungalow colony and the city's final beachfront bungalow colony (with a few exceptions, the houses stood in a single line right on the beach).

Between 1958 and 1962, all the private property along the waterfront in this area was acquired by the city via eminent domain to make way for a proposed shorefront parkway that never ended up getting built. Most of the buildings on the condemned land were demolished, including, as we've learned, dozens of bungalows in neighboring New Dorp Beach, but the Cedar Grove bungalows were left intact. Having become city property, they were then rented back to the former owners, who continued spending their summers here. 22 of the houses had to be leveled after sustaining heavy damage during a nor'easter in 1992, but the other 42 remained as a seasonal getaway.

After the summer of 2010, the city ended its rental agreement with the residents, intending to bulldoze most of the buildings and open up better public access to the beach. The bungalows left standing, as many as seven of them, would be transformed into various park facilities. The two houses you see above are the only ones that ended up being spared (as evidenced by pre-Sandy aerial photos), and it appears that they are now going to be demolished as well because of damage from Hurricane Sandy. So long, Cedar Grove.

The old parachute drying tower (left) and Elm Tree Lighthouse at Miller Field

The narrow roadways in the surviving inland section of New Dorp Beach reflect the neighborhood's origins as a bungalow colony (Street View).

The house that once stood here was demolished after being wrecked by Hurricane Sandy. The owners of this property, Sheila and Dominic Traina, also lost other buildings in the neighborhood, including their own home at 67 Cedar Grove Avenue. A mini-controversy ensued when Allstate used footage of their destroyed house in a back-patting post-Sandy commercial even as the insurance company was denying the Trainas what they believed to be fair compensation for their losses. After the wreckage of the house was cleared, the flag-painting Staten Island artist Scott LoBaido installed a sculpture on the lot entitled Waiting, which "symbolize[d] the frustrating world of Island survivors of the storm. After lives lost, homes damaged or demolished, possessions ruined, most find themselves in a bureaucratic limbo, waiting for help that never seems to arrive."

This marshside beacon (bird's eye view) serves as the front range light for the Swash Channel in Lower New York Bay. (The rear range light is located farther inland and at a higher elevation. When the two lights are aligned from a ship's point of view, that means the ship is correctly lined up with the channel and can safely proceed through it. Here's an example of what two aligned range lights look like.) The Elm Tree Lighthouse (which we saw earlier today) and the New Dorp Lighthouse served as the front and rear range lights, respectively, for the channel until 1964, when the tower pictured above became the new front light and the stately Staten Island Lighthouse, which was already in use as the rear light for the heavily trafficked Ambrose Channel, had a second light added to it so it could also function as the rear light for the Swash Channel.

Welcome to the LoBraico family theater. Just pull up to the curb and tune your radio to 88.1 FM. Now playing: The Polar Express.

For three blocks, this little drainage channel takes the place of Adelaide Avenue, severing Medina Street and Tarrytown Avenue in the process.