Nothing new here: "When neighbors are talking in Midland Beach, they say, 'Which lake do you live on?' "

This former Army airfield, established just after World War I, is now part of Gateway National Recreation Area. Most of the property is currently covered with athletic fields, but the building above, erected in 1920 as a double seaplane hangar, serves as a reminder of the site's aviatic past. At right is the old Elm Tree Lighthouse, a namesake of the original nautical beacon that stood in this area: a large elm tree at the foot of New Dorp Lane that ships used as a navigational landmark. The similar-looking brick pillar is a former parachute drying tower.

I've briefly mentioned Miller Field once before on this blog, by the way, as the site where an airliner hurtled into the ground following a mid-air collision in 1960 — a disaster commonly known as the Park Slope plane crash, named for the residential neighborhood in Brooklyn where the other airliner went down.

There is a group of 13 or so houses standing in Miller Field; they apparently date back to when the site was an Army airfield. Given that they're now located in the middle of a park (Miller Field is part of Gateway National Recreation Area), I was surprised to find that they're still used as residences! One woman standing in front of her house told me that only National Park Service workers and certain other federal employees (and their families) are eligible to live in them. You can see the houses and the neighboring soccer fields in this aerial view.

Standing in a sea of front-yard concrete. This is not the first such scene we've seen, although in this case the little donkey appears to be part of a memorial to a deceased pet dog.

Scott LoBaido continues to redefine the American flag mural.

This postal receptacle is modeled after the Friendship Firehouse in Alexandria, Virginia. Now a museum, the building was once home to the Friendship Fire Company, established in 1774, whose first fire engine was purchased by George Washington.

Mostly hidden in the woods inside Prospect Park, this still-active Quaker burial ground, established in 1849, is older than the park itself, which was built around it beginning in 1866. The 10-acre cemetery contains over 2,000 graves marked with simple headstones like the ones you see above. It is generally off limits to the public, although tours are occasionally given. Even on those tours, however, the location of the grave of the cemetery's most famous resident, Montgomery Clift, is kept a secret.

Peering through the gate at the rather inconspicuous entrance to Friends Cemetery in Prospect Park

Towering in the background is the long-defunct Parachute Jump, an amusement ride relocated to Coney Island from the 1939-40 World's Fair. Just last year, the Parachute Jump's lighting scheme was given a $2 million upgrade — check it out!

In 1916, Nathan Handwerker opened a frankfurter stand here at the corner of Surf and Stillwell Avenues in Coney Island. From that point on, for over 96 years, this flagship Nathan's reportedly opened for business every single day until it was finally forced to close by Hurricane Sandy. (Damage from the storm kept the place shuttered for several months.)

From a previous post about Charles Feltman, the purported inventor of the hot dog:

Feltman died in 1910, but his restaurant stayed in business, and it was a few years later that a young Polish immigrant named Nathan Handwerker found work there slicing rolls. Supposedly with some encouragement and borrowed money from his then-unknown co-workers Eddie Cantor and Jimmy Durante, Nathan opened his own hot dog joint in 1916 at the corner of Surf and Stillwell Avenues, where he and his wife served up frankfurters for just a nickel apiece, half the price his former employer charged.

According to legend (and Nathan's grandson), with some variations from one telling to another, people were initially skeptical about the quality and contents of a wiener that could be sold for a mere five cents. To alleviate these concerns, Nathan hired people to dress as doctors and eat hot dogs in front of his stand, giving the impression that medical professionals considered his food perfectly healthy. Before long, with the arrival of the subway in Coney Island (and with the terminal station located right across the street), the dogs started selling like crazy, and now, almost a century later, Nathan's Famous remains a household name.

Os Gêmeos, identical-twin artists from Brazil, painted this eerily fanciful mural across from the Coney Island subway terminal back in 2005. For a much clearer view, check out this stitched-together image of the entire wall.

That's the Cyclone at left and the Wonder Wheel at right. I wasn't actually walking when I took this photo (don't tell); I was heading home on the Q train at the end of the day.

past the old Troop C Armory on Bedford Avenue in Crown Heights. This and the next few images are from a short unofficial stroll around the neighborhood.

Erected in 1920, this former Studebaker showroom (circa-1942 photo) dates back to the days when this stretch of Bedford Avenue was known as Automobile Row. The building has since been converted into low-income apartments, but some traces of its original occupant still remain, most notably the terra-cotta wheel logos (close-up) at the top of the facade. Perhaps you recall seeing those same logos on an old Studebaker finishing facility up in Manhattanville a couple of months ago.

Like the Studebaker Building that stands across the street, this two-story brick structure was once an automobile showroom. (It looks more showroom-like from the other side.) It later — some sources say 1929 or 1930, but ads from 1932 still list an auto dealer at this address — became the home of Loehmann's, the legendary discount designer women's clothing store started by Frieda Loehmann after her flutist husband's paralyzed lip left the family in need of a stable income.

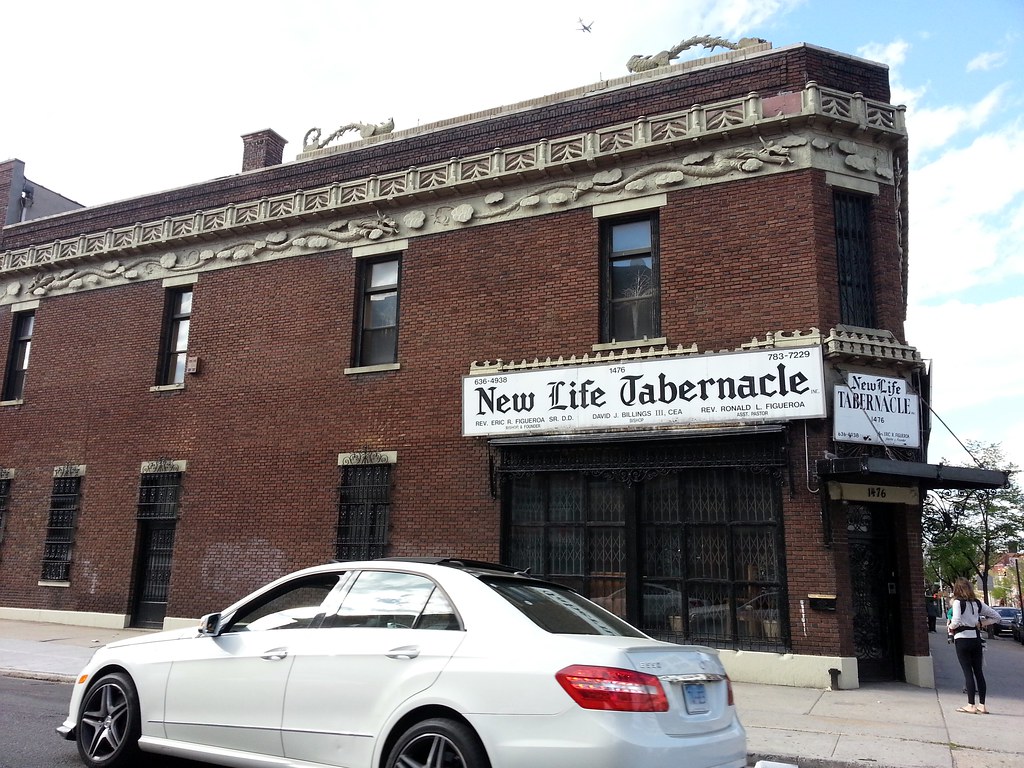

At first glance, the building is nothing to write home about, but then you start to notice a few things, like the dragons flying through the clouds on the frieze. Mrs. Loehmann had a fondness for such over-the-top ornamentation; in fact, the place looked even more outlandish in its heyday — take a peek at what's hidden beneath those church signs. And the interior was a sight to behold as well:

Hundreds of racks of clothes failed to dim the theatrical splendor inside. The decor was compounded of marble floors from Italian palazzos, antique Italian wall paneling, huge Italian marble statues and junk that Mrs. Loehmann couldn't resist from Seventh Avenue showrooms that closed. Her chairs were all covered in old fur coats. She had a leopard sofa with nutria.Not to mention the "chandeliers, dripping prisms, enormous paintings, Venetian columns festooned in gold, lions in iron and lions in marble, huge lanterns and torchieres with figures holding clusters of lights aloft". All of these furnishings were auctioned off in 1962 after Mrs. Loehmann died, but many of them were acquired by a clothier named Martin Kogut who restored much of the decor when he opened his own store in the building. Here are three grainy photos of the interior of his store in 1966, along with other pictures of the building in different eras. As you can see in a couple of those shots, the church that currently occupies the place decided to retain some of the decor.

One might suspect that Mrs. Loehmann intended the lavish furnishings to imbue the shopping experience with an air of refinement, but the actual scene at her store was apparently rather primal, with women aggressively competing to find the best bargains and stripping down in the open to try on the merchandise — there were famously no dressing rooms at Loehmann's. (The Loehmann's stores that recently went out of business were an offshoot of Mrs. Loehmann's standalone establishment, but they also offered communal changing areas.) Here's how a reporter for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle described his trip to Loehmann's with his wife in 1954:

Loehmann's, on Bedford Ave. — with its stained glass peacocks and carved dragons — looks from the outside like the pleasure dome of Kubla Khan. Inside, it has much the same atmosphere as a capsizing ferryboat. . . .

[Women] invade the place daily in ravening hordes to peel non-chalantly before a gallery of gaping husbands and do battle for the prizes hidden away among the dress racks. . . .

In a small arena walled by dress racks, a battalion of frenzied females was stripping off its outer garments and mounting an assault wave on Mrs. Loehmann's wares. Some of the women were practically stripping one another.

A few of the lady shoppers, to the special satisfaction of the spectators' gallery, were wearing two-piece affairs and I even caught a couple of glimpses of black lace.

Speaking of such names, the Bronx is home to tens of thousands of Albanian-Americans. While searching for information on this subject, I came across two interesting articles: 1) a 2001 piece about the dozens of Italian restaurants in the NYC metro area that are actually run by Albanians, and 2) a 1999 story about local Albanians preparing to enlist as volunteers in the Kosovo Liberation Army:

Scores of them, from youths barely out of high school to grizzled men old enough to be their grandfathers, jammed [Frank's Sport Shop on East Tremont Avenue] to buy fatigues, pistol belts, compasses, boots and night-vision binoculars. Duty dictated that they fight for a place some of them had never visited or a country others left decades ago.

The long, curving approach on the Bronx side of the Throgs Neck Bridge