The second entrance to the 191st Street station is located on top of the hill, and the only way to get from there to the train platforms is to take an elevator. There are four elevator cars, and one of them has a permanent human operator whose job is, basically, to press the elevator buttons periodically. It may seem silly to pay someone to do that, but there are a lot of people who feel much safer taking a long elevator ride if there's someone there to keep an eye on things.

The pedestrian tunnel connects to the elevator area outside of fare control, so people who are not riding the subway can still use the elevator as an easy (and free) way to get to and from the top of the hill.

Apparently the attendants (there are four other stations where they're employed, all in this hilly part of Upper Manhattan) used to be allowed to decorate their elevators, but the MTA has since cracked down on that freedom of expression.

Those tall apartment buildings in the background are two of the four built over the Trans-Manhattan Expressway.

This older gentleman, while slowly making his way up the hill, reached into his shopping bag and extracted a couple handfuls of unpopped popcorn, which he then tossed to the mob of pigeons currently snacking upon them. It's good to see New York's pigeon feeders branching out from the ever-so-clichéd bread crumbs.

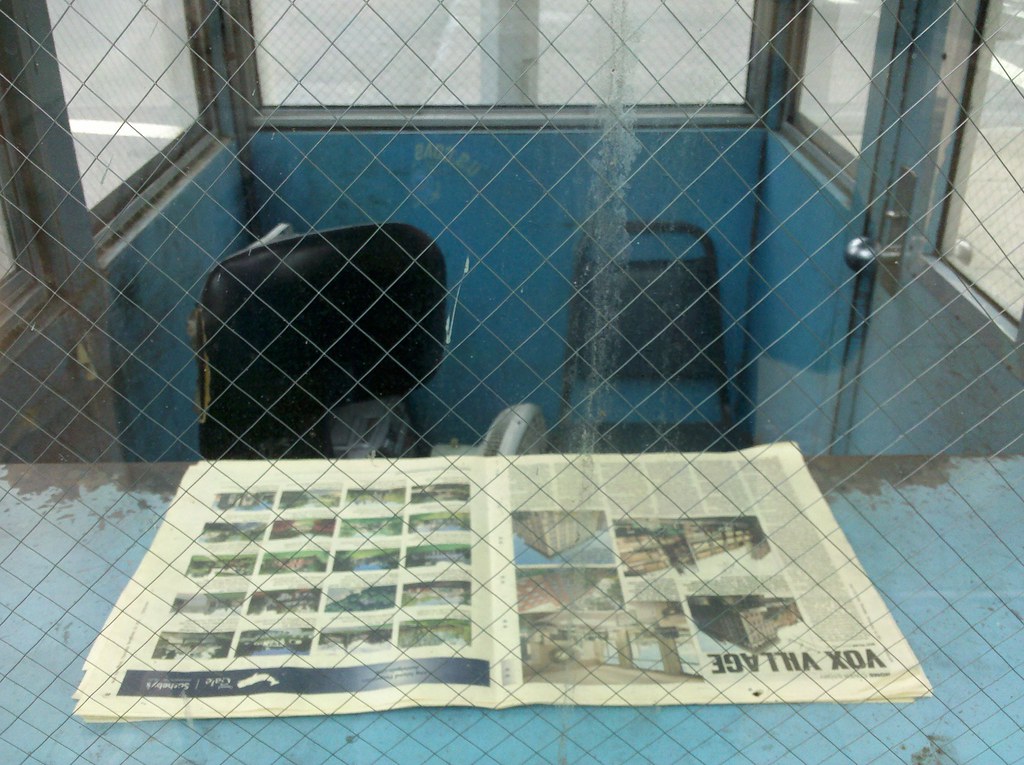

I've seen a few of these little NYPD booths elsewhere in the city, but I must have passed by at least half a dozen (not counting a couple of similar private security shacks) today while walking around Yeshiva University in Washington Heights. I'd guess it's been a while since this one was last used: that copy of the New York Post is from November 10th of last year.

There's no sign indicating what this fenced-in area is, but it has the feel of a memorial garden. Which would be fitting, given the man for whom the surrounding playground is named.

Broadway runs through a steep valley in this part of Manhattan, somewhere out of sight beneath all those barren limbs. You can see the top of the cliff on the other side of the valley, where street level is considerably higher than the roofs of the multi-story buildings one block closer to the camera.

That's the Washington Bridge, mind you; not to be confused with the nearby George Washington Bridge.

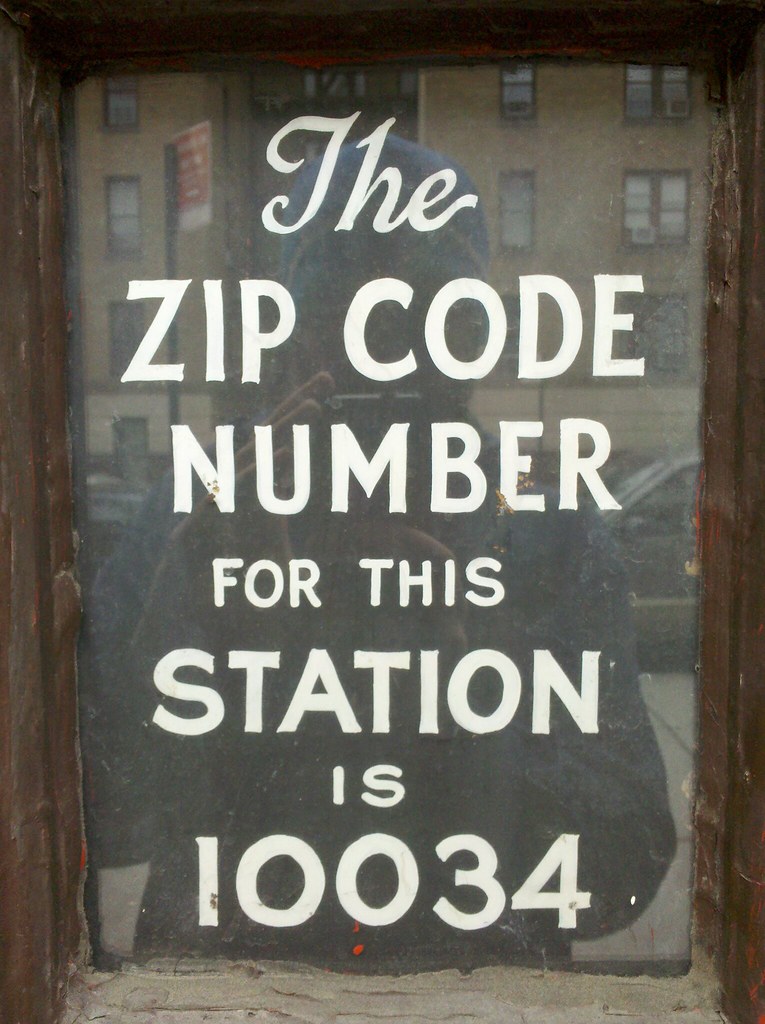

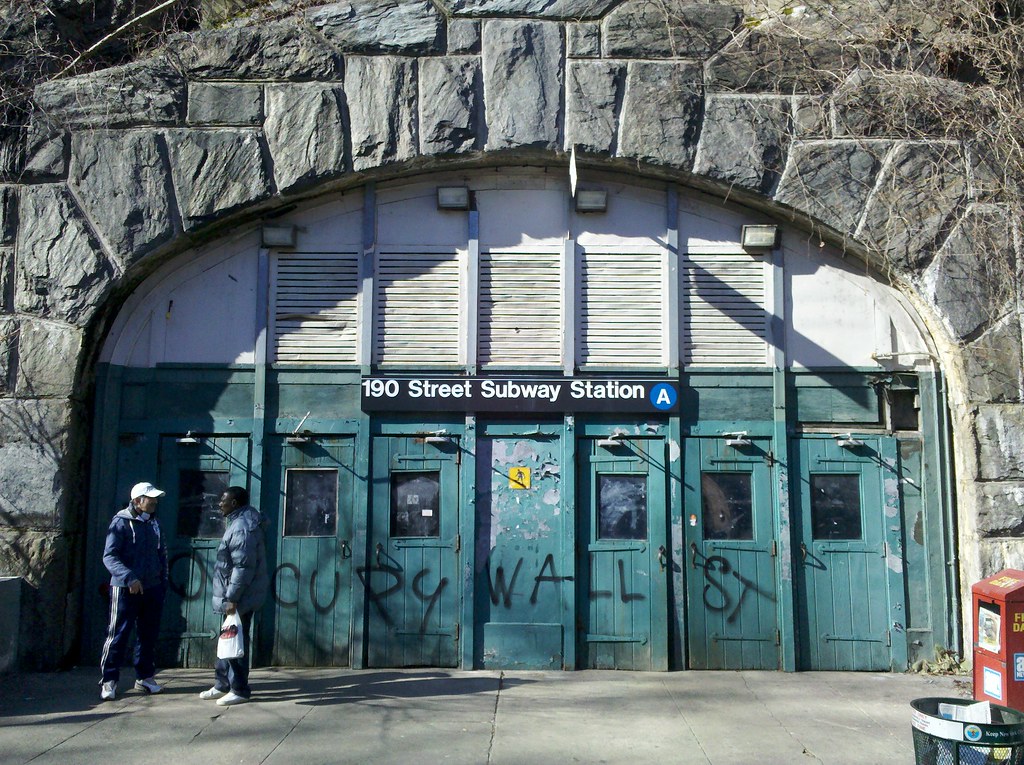

This is the 190th Street A station, where Victor Hess performed his subterranean radiation research.

You can see three of our old acquaintances in this photo. Two are pretty easy to spot; the third (which we haven't actually seen before — we've just seen the same type of thing) is not. Need a hint for Thing No. 3?

Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter II, better known as Reverend Ike, was a charismatic, flamboyant preacher who, during his 1970s heyday, spread his prosperity-based doctrine of the Science of Living to a TV and radio audience of some 2.5 million people, becoming a multimillionaire in the process. In 1969, he purchased the former Loew's 175th Street Theatre, a "delirious masterpiece" built in the "Byzantine-Romanesque-Indo-Hindu-Sino-Moorish-Persian-Eclectic-Rococo-Deco style", and turned it into his headquarters, renaming it the Palace Cathedral. (It's also known as the United Palace Theatre in its more recent role as a part-time music venue.) Rev. Ike passed away in 2009, and his son has since taken the reins of the church. Hopefully I'll find myself back here on a Sunday and will be able to take a peek inside.

This World War I memorial stands in Mitchel Square, across from NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center. There are no typos in the previous sentence.

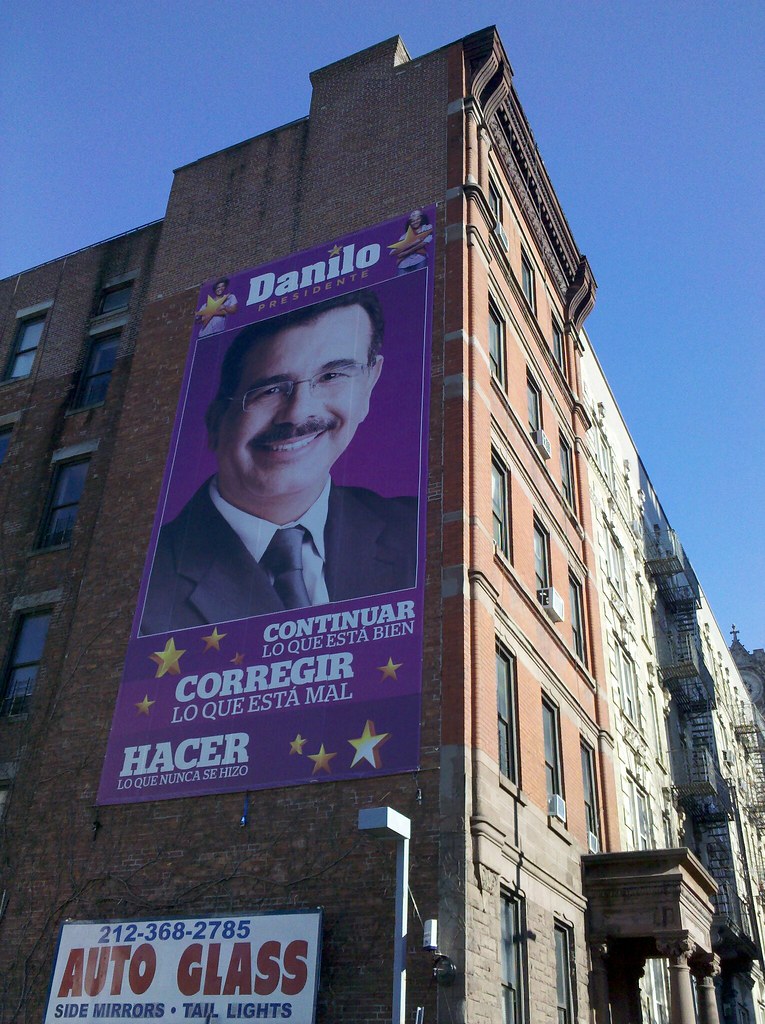

He's running for president of the Dominican Republic. I learned this when I saw his face a hundred times today in Washington Heights and Inwood. There are almost 600,000 Dominicans living in NYC (making them the most populous foreign nationality in the city), and since 2004 they've been able to cast votes for their national elections from polling centers here in New York.

The estate of the famed naturalist and painter lay just across 155th Street from Trinity Church Cemetery, where this monument stands.

Completed in 1848, it's the oldest bridge still standing in NYC (sort of — in order to improve navigation on the Harlem River, five of the original masonry arches were replaced by a single steel arch in 1927). A beautiful, stately structure in its own right, it was but one component of a truly extraordinary engineering project.

There are several plaques like this around Swindler Cove Park providing information on the construction of homes for different types of wild animals, from bats to owls to squirrels.

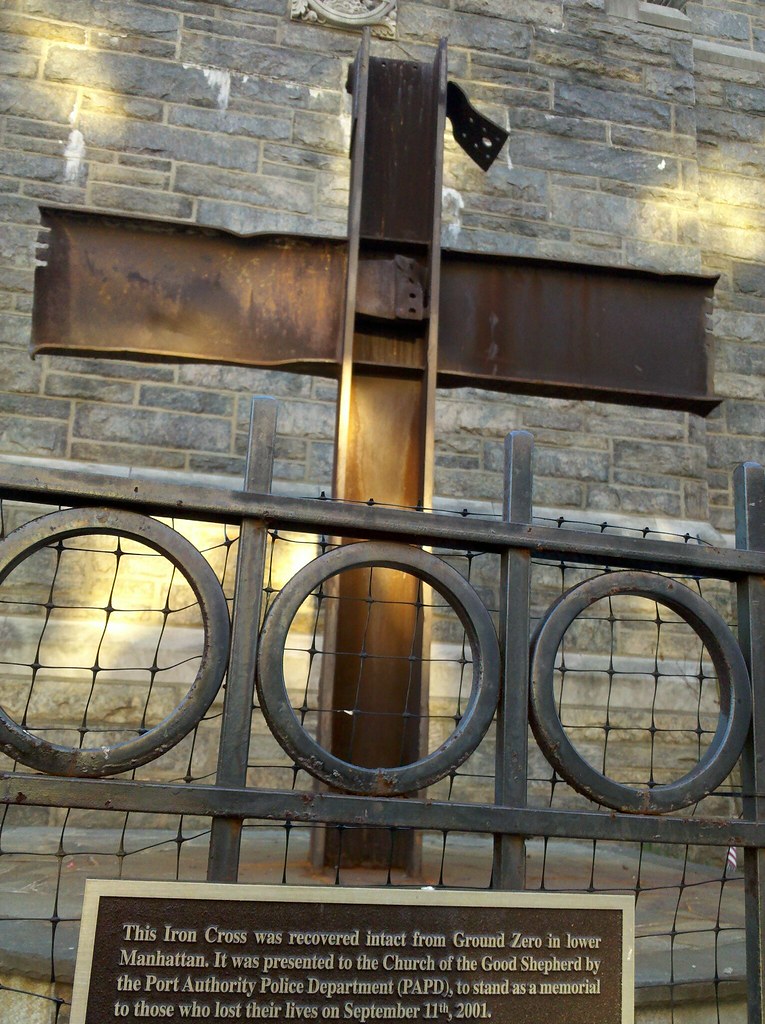

Technical note: There are tons of streets in New York that have been renamed for heroes and victims of 9/11. For the purposes of enumerating 9/11 memorials, and because they have so much in common with one another, I'm going to count all the renamed streets as individual components of one large citywide memorial. Memorial #11 was the first renamed street I noticed, so I'll consider all other renamed streets to be part of #11 as well.

This city seal predates 1915, when a uniform standard was created. It's quite unusual to see the fire department referred to as NYFD instead of FDNY; perhaps that was a more common abbreviation in the days of yore.

The Dyckman family had acquired around 250 acres of farmland here in northern Manhattan by the time of the Revolutionary War. They fled Manhattan when the British forces captured and occupied it in late 1776, and they didn't return until it was back in American hands after the end of the war in 1783. The British had destroyed their home during the war, so the Dyckmans built this farmhouse to take its place.

About a quarter of the British fighting forces in the Revolution were actually German soldiers hired out, often against their will, by their princes. Almost half of these 30,000 troops hailed from the principality of Hesse-Kassel, and so the lot of them became known as Hessians. In 1914, a local amateur archaeologist by the name of Reginald Pelham Bolton discovered a Hessian encampment that had been built on the Dyckman farm during the war. He reconstructed this hut, which would have housed six to eight Hessians, on the grounds of the Dyckman Farmhouse, which was just being restored at that time.

While wandering through Inwood Hill Park today, I came upon a group of people gazing up at a tree. It turns out they were looking at a Great Horned Owl, hidden amongst the leaves of the dead branch hanging down from the tree in the center of the photo. After a sufficient amount of intent staring, I was finally able to see it. (It's in this photo, but it's completely indistinguishable.)

I hung around for a little after everyone else took off, and then started on my way again. A couple of minutes later, I ran into two older Korean men who had heard about the owl and were wondering exactly where it was, so I took them over to the tree and pointed it out to them. One of the men was wearing a fedora and a bright turquoise scarf, which reminded me of something I had seen before...

On a previous walk through Inwood Hill Park, I found some mysterious circles carved into the soil. They contained patterns of different shapes and textures and colors, and were made entirely with materials from the surrounding forest. They were very thoughtfully constructed, and had clearly required a lot of time and effort. A guy (who happened to be Phil Roy) came by walking his dog, and I asked him if he knew what these circles were. He told me all about an older Korean guy, named Young, who comes out to the park every day and works on them. When I got home I searched the internet for information about Young, and stumbled upon an incredible video of him calling a woodpecker and then feeding it in his hand. I was completely transfixed, not just by the beautiful bird, but by something in Young's demeanor, and I watched the video several times.

Ten months later, when I ran into two older Korean gentlemen on a trail in Inwood Hill Park, and I saw a familiar-looking face and hat and scarf, something clicked...

Young gave me a tour of his creations, which number about three times what you see in this picture and the previous one. This piece represents the endless cycle of water flowing to the sea, evaporating, and returning to the earth as rain.

Young retired in 2007, and ever since then he's been coming to the park every day — rain or shine, summer or winter — to work on his "garden" (my term, not his) and spend time walking in the woods. He says he can feel a tremendous power coming from the earth when he is forming these shapes and patterns. To my eye, they are beautiful works of art, but I think to Young they are much more spiritual in nature.

Inwood Hill Park contains the last real forest in Manhattan. The towering trees, rock outcroppings, and isolating topography make it the only place on the island where you can really get a sense of what things were like before the arrival of the Europeans. It's an extraordinary enclave of rooted history in a city that's constantly in flux. Could Young's work exist anywhere else?

The vulnerability of these pieces to the weather and other natural processes is integral to their power, and it also means Young has an ever-changing canvas on which to work. If you're ever in the area, just head down into the valley between the two ridges in the park. Keep walking along the main north-south trail, and you'll find the garden soon enough.