Back in the 1980s, the rector of St. Bart's led a divisive and controversial attempt to secure the church's finances with the construction of a towering glass skyscraper on the site of its community house (the brick and stone building extending from the right side of the church). His plan was strongly opposed not only by preservationists (including, once again, Jackie Kennedy Onassis), but by many parishioners as well.

When the skyscraper scheme met its official demise in 1991 at the hands of the Supreme Court, the church seemed to be on its last legs, with dwindling attendance and a shrinking endowment. But a new rector took the reins in 1994, introducing a "theology of radical welcome" and gradually bringing people back to the church. By the time he retired early last year, the congregation had grown from 150 to almost 3,400. (He also had his own ideas for making some money off the community house: he opened a restaurant inside it, with a warm-weather outdoor dining area, visible above, on the church's terrace.)

Factlet of the day: St. Bart's has the largest organ in NYC!

This triple portal at St. Bartholomew's was originally part of a prior incarnation of the church several blocks away.

In the foreground: the men-only Racquet and Tennis Club, "home to some of the most arcane sports in the world". Rising behind it: Park Avenue Plaza, whose developers bought the club's air rights for $5 million in the late 1970s after "perhaps the biggest game of real estate 'chicken' ever played in New York." The biggest, sure, but certainly not the most hilarious.

is the name of this bronze replica of Scabby the Rat currently on view at Lever House. The courtyard in which the rat sits is private property, but it's open to the public at all times, with one exception. "In a practice going back to 1953 and a custom that can be traced to Anglo-Saxon England", the courtyard is closed for part of one day each year to provide the owners with a solid legal defense against any potential claims of adverse possession, even though it now "seems inconceivable that Park Avenue passers-by could ever make a claim that they are the actual owners of Lever House’s courtyard."

Ever since I watched Coming to America as a kid, the Waldorf has been synonymous in my mind with luxury. So I was quite surprised when I moved to New York and saw how dirty its facade was. I assumed this must be an old joke around here, this fancy hotel with the gross-looking exterior, but no one ever seemed to know what I was talking about when I brought it up. Even online I could only find one mention, on some weird website, about this "pitiful sight".

Well, as you can see, the building has finally been given a thorough cleaning. Surely, I thought, this would be big enough news to merit at least a passing mention on a blog somewhere. But there's nothing! The whole internet is silent about it.

Until now.

With Summer Streets still in full swing, I'm looking down at the Yellow River of 42nd Street from the Park Avenue Viaduct.

During the last few decades of his life, the visionary inventor, who at one point had a laboratory located down the block at 8 West 40th Street, came here to Bryant Park on a regular basis to feed his beloved pigeons.

In his words:

Sometimes I feel that by not marrying I made too great a sacrifice to my work . . . so I have decided to lavish all the affection of a man no longer young on the feathery tribe. I am satisfied if anything I do will live for posterity. But to care for those homeless, hungry or sick birds is the delight of my life. It is my only means of playing.and:

I have been feeding pigeons, thousands of them for years. But there was one, a beautiful bird, pure white with light grey tips on its wings; that one was different. It was a female. I had only to wish and call her and she would come flying to me.

I loved that pigeon as a man loves a [woman], and she loved me. As long as I had her, there was a purpose to my life.

The Timeshare Backyard has bitten the dust; the lot has been sold to a developer.

A halfhearted attempt to pass as a classic NYC taxicab

Something I never knew before I started this walk: there are approximately 500 gazillion fig trees in New York City. In some parts of the outer boroughs, I'll see a dozen or more each day. This particular fig is of the Brown Turkey variety, but you can find other types growing in the city as well.

While we think of figs as individual fruits, they're actually inside-out inflorescences — each of those fleshy little strands is actually a tiny flower! But how on earth do these flowers get pollinated? As we learned earlier, figs have an amazing relationship with a very small, specialized kind of wasp:

A female wasp of this type is able to crawl inside a fig through a tiny opening opposite the stem. Once inside, she lays her eggs, and in the process transfers pollen from the fig in which she was born. The larvae feed on the individual flowers in which they are growing until they reach maturity, at which point the males and females mate. The males then chew tunnels leading out of the fig and subsequently die, and the females (bearing pollen from the fig's flowers) escape through these tunnels and seek out new figs in which they can lay eggs of their own.Things get a bit more complicated — and interesting — with gynodioecious species (whose ranks include the figs typically grown in the US); you can learn more about them here if you are so inclined.

I should also note that the fig cultivars generally found in NYC, like the Brown Turkey, are parthenocarpic, which means they produce sterile fruit that does not require pollination — or wasps — to develop. (California's Calimyrna figs, on the other hand, must be pollinated for the fruit to mature. This has resulted in a strange-looking annual ritual in which paper bags are stapled to thousands of acres of fig trees.)

(Sound/look familiar?)

I'm not sure when the squat brick addition in the front was built, but the more elaborate structure rising behind it, currently home to a dance studio, deli, and kids' party center, was erected in 1901 as a public school. After the school closed in 1945, the building became a factory for the Marimac Novelty Company.

I think these massive steel braces are going to be (or maybe already have been) used for trench shoring during the installation of new sewer and water lines in the area.

This cemetery ("one of the nation's most important black burial grounds") and its associated church were established around 1850 by residents of Sandy Ground, a community of free blacks dating back to the late 1820s. By the 1850s, many African-American oystermen and their families had moved to the area from Maryland, driven north by a series of racial laws enacted by the state that made it difficult for them to do business there. They were attracted to Sandy Ground because of its proximity to the renowned oyster beds of Prince's Bay, just a couple of miles to the south.

Oystering became the central industry of Sandy Ground, and the village thrived for several decades before gradually falling into decline after heavy pollution and outbreaks of typhoid led to the closing of Staten Island's oyster beds in 1916. Fires in 1930 and 1963 further decimated the surviving community, but there are still a handful of families in the area who can trace their lineage back to the original black settlers.

(If you look closely, you can see a deer prancing around the edge of the cemetery.)

Look closely again; you can see two deer this time — a doe and a fawn. There was a third one traipsing about as well, but I can't spot it in this photo.

The society runs a museum and library focused on — you guessed it — the history of Sandy Ground.

Once again, I was doing some unofficial walking and spotted something I missed before. I don't know how on earth I didn't notice this memorial the first time I walked by — it's humongous! And it looks to have made a full recovery since it was vandalized in 2003. You can see the individual sections in more detail here.

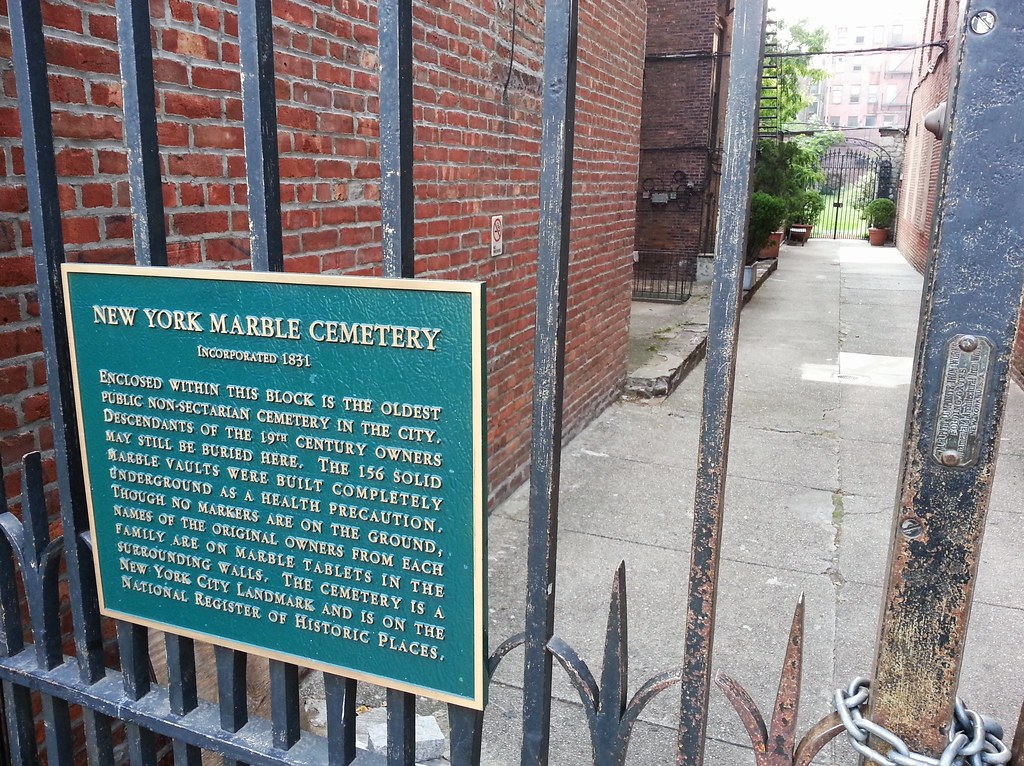

Founded in 1830, the New York Marble Cemetery is the oldest non-sectarian cemetery in the city. It's entirely enclosed within a block of buildings in the East Village (aerial view), and the only access is through this little alleyway off of 2nd Avenue. The gates are generally locked, but the cemetery is opened to the public occasionally and is also rented out for events, including weddings! (There are no grave markers, just plaques on the walls identifying the families interred here. This makes the place look more like a private courtyard than a graveyard, which probably helps explain its desirability as a party location.)

At the time the cemetery was established, recent outbreaks of yellow fever had led to a prohibition against earthen burials. Consequently, everyone interred here is entombed inside one of 156 subterranean marble vaults — hence the name of the cemetery. (The almost identical-sounding New York City Marble Cemetery, just one block away, is unrelated to this one, but its name also derives from its marble tombs.) No one has been laid to rest here since 1937, but the cemetery still has a policy allowing descendants of the original vault owners to be buried here if they so choose.

Here's what the NY Times had to say about this marine salvage yard, more popularly known as the "ship graveyard" or "boat graveyard", back in 1990:

For decades the Witte Marine Equipment Company, the lone remaining commercial marine-salvage yard in the city, has given mothballed, scuttled, abandoned and wrecked ships of all sizes a final port. Through the years it has become, an "accidental marine museum," as a nautical magazine described it, with one of the world's largest collections of historic ships.There were once some 400 vessels to be found here, resting in the muck along a bend of the Arthur Kill. While there are far fewer today — old man Witte's successors have dismantled many of the boats since his passing in 1980 — the ship graveyard, now owned by the Donjon Marine Company, still makes for quite an impressive sight. This aerial view will help you get a sense of things, and, if you're interested, you can find many more photos of the place here.

To historians like Norman Brouwer, curator of the South Street Seaport Museum, it "is a tableau of the history of shipping in New York."

Once the world's largest landfill; soon(ish — maybe 25 years from now) to be a 2,200-acre park, the second-largest in the city. And there might be goats, too!