As "The Newspaper of Torah Jewry", Hamodia's slogan is:

A newspaper upstanding enough to bring home [e.g., photos of women — or even their shoes, apparently — are forbidden] and outstanding enough to bring anywhere

From its storefront tenants to its architectural frills, this building is all about appearances.

For a deeper appreciation of this ridiculous name, check out the former occupant of this storefront.

Opened in 1897, this warehouse complex was once much slimmer. It was then expanded in stages, reaching its current size by 1915.

Now the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Harvey Theater, the Majestic "was built in 1904 as a legitimate theater, and spent many years as a movie theater and church before being abandoned in 1968. It was reclaimed by the Brooklyn Academy [in 1987], and reopened [that] October after a seven-month, $5 million renovation that intentionally left plaster exposed, paint crumbling and the theater in a state of studied ruin."

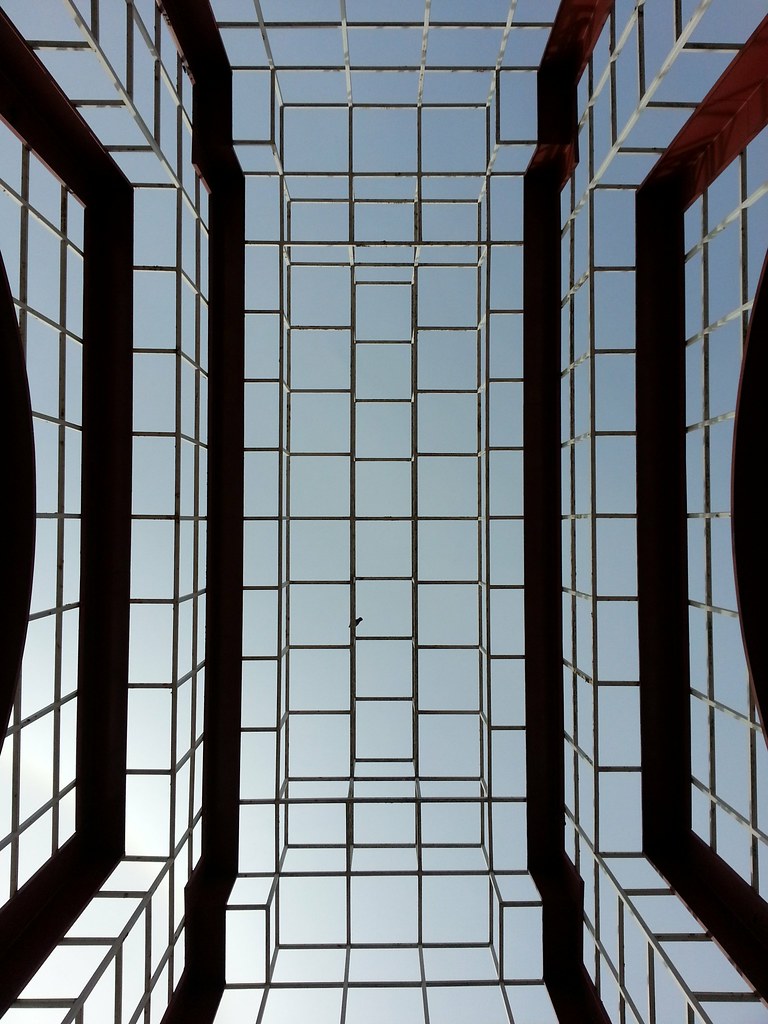

Opened in 1919, this building operated as a theater of one sort or another for almost four decades. After a stint as a bowling alley, it was converted into manufacturing space sometime in the 1960s. Recently renovated, it is now home to BRIC House, "a multidisciplinary arts and media center designed to support artists and engage the public", and UrbanGlass, an organization "committed to furthering the use of glass as a creative medium." You can see some interior photos here.

Opened in 1928, the former Paramount Theatre currently serves as the Arnold and Marie Schwartz Athletic Center at Long Island University's Brooklyn campus. Check out this breathtaking shot of the gymnasium, and then take this fantastic photo tour through the whole building.

This massive sculpture at Long Island University's Brooklyn campus was inspired by the Soldiers' and Sailors' Arch at Grand Army Plaza.

on the grounds of Long Island University's Brooklyn campus

When it was built in 1894, this church had a greater seating capacity than any other in Brooklyn or New York City. (At the time, NYC comprised only Manhattan and part of the Bronx.) It was rebuilt after being devastated by a fire in 1917, and was damaged once again by a blaze in 2010. Short on funds to repair the interior and replace the roof, church officials are now looking for someone to redevelop the site into a mixed-use facility that would still provide a place of worship for the congregation. Ideally, the church would like the existing structure maintained and built on top of rather than demolished, but that may prove unfeasible.

This building was erected in 1903; its predecessor, completed in 1823, was the first Catholic church on Long Island, and became the cathedral of the Diocese of Brooklyn when the diocese was established in 1853. St. James was the sole seat of the bishop for the next 160 years, although its status was downgraded to pro-cathedral from 1896 to 1972 in anticipation of the construction of a colossal cathedral that never ended up being built. Just last year, however, the much larger St. Joseph's in Prospect Heights, capable of hosting the big events that St. James can't, was named co-cathedral of the diocese. (Prior to this designation, major diocesan gatherings were traditionally held at the gigantic Basilica of Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Sunset Park.)

Pope John Paul II visited St. James in 1979, and, according to a plaque on the front of the church, "He walked in our midst, touched our hearts and despite torrential rain, he brought the sun".

Opened in 1848, today's Borough Hall was originally Brooklyn's City Hall, serving in that capacity for the 50 years preceding Brooklyn's incorporation into New York City.

There are numerous bands and cables tied to the columns of Borough Hall. (They're partially visible in the previous photo as well, if you look closely.) At first, I assumed they must be serving some important structural function, but it looks like they're actually just there to hold up big colorful banners from time to time.

The center of Brooklyn's bureaucracy, completed in 1926, is now being partially converted into commercial space. A candy store and a Sephora have already opened here; a yoga studio and a Neiman Marcus are on the way.

This painted sign was recently uncovered when the building next door was demolished. Chandler, whose featured line of pianos was Ivers & Pond, was founded in 1869, and was said to be Brooklyn's oldest piano house when it moved from this location in 1928.

These kitty condos, two of the dozen or so I saw today at the northern end of Morningside Park (there's a third one partially visible higher up on the rocks), provide shelter for the park's sizable feral cat population. They read: "NYC Animal Research Do Not Remove". I called the phone number written on the boxes; the guy who answered told me they're spaying and neutering the cats, trying to find homes for the friendly ones, and putting out these little huts so the wild ones can stay warm through the winter.

West 130th Street between 12th Avenue and Broadway is only the second section of road I've encountered that's been closed not just to cars but also to pedestrians. (The first was East 146th Street/Canal Place in the Bronx.) I'll have to come back and walk it once it reopens, although it's not clear when that will happen. It's already past the date on the sign, and, as you'll see, the street is nowhere close to being open, or even to being recognizable as a street...

This road closure and reconstruction is part of Columbia University's massive and controversial expansion into Manhattanville. The building rising in the back, the first structure to take shape on the new campus, is the Jerome L. Greene Science Center.

Peering west across Columbia's construction site toward the Riverside Drive viaduct

Erected around 1923 as a finishing facility for newly manufactured Studebakers, this building has subsequently served as a milk processing plant and has housed, among other things, a doll factory and part of the American Museum of Natural History's Polynesian antiquities collection. Columbia University has rented space here for over two decades and now plans to incorporate the building into its new Manhattanville campus, making it one of only a few existing buildings within the bounds of the future campus that will still be standing when construction is complete in two decades or so.

Owned by Columbia University since 1949, this 1911 building was originally a milk processing plant operated by Sheffield Farms (whose "Class I gravity milk plant" — one of only two in the country when it opened in 1914 — we saw in the Bronx). Sheffield was later joined in the neighborhood by Borden, which converted the nearby Studebaker building into a milk plant in 1937.

of part of Columbia University's future campus in Manhattanville. Standing atop the Riverside Drive viaduct, we're looking east at the skeleton of the new Jerome L. Greene Science Center, with the elevated 1 train crossing 125th Street in the background at right. 130th Street used to run right down the middle of this scene, and eventually will once again.

Currently used for self-storage, this classically styled edifice was built in the late 1920s as a "furniture warehouse", according to a 1998 NY Times article. "The columns and pilasters mask a cavernous interior, containing over 1,000 storage rooms and vaults, built of thick concrete and steel and dispersed over 14 floors. Roughly half the floors are built below street level, far below the [Riverside Drive] viaduct" (on which I'm standing). This view from down below on the Henry Hudson Parkway makes the actual size of the building a little clearer.

The architect was George S. Kingsley, who "designed several other historically inspired storage warehouses", including the similar Atlas Storage building in Philadelphia and the Egyptian Revival Reebie Storage Warehouse in Chicago. Even given the different architectural standards of that era, it seems kind of odd that such refined designs were employed for these utilitarian structures. The reason for this, I think, is obscured by the vague descriptions of these facilities as "furniture warehouses" or "storage warehouses". What does that mean exactly?

We start to get a better sense when we find out that Mr. Kingsley's architectural specialty was "secure storage for shorebound summer vacationers". And a while back, when passing by the Portovaults of Day & Meyer, Murray & Young, we learned that the well-to-do once "stored seasonally . . . When people went away for the summer, they rolled up their rugs and took their silver and put it in storage." So I'd imagine that the clientele of these former businesses was considerably wealthier than the budget-conscious customers of today's self-storage warehouses. Perhaps the grand, imposing architecture was important for appealing to that snootier demographic.

This building, featuring one of renowned theater architect Thomas Lamb's "most ebullient facades", originally contained the lobby of the 1913 Hamilton Theater. In recent years, it has served as the home of at least two discount retail stores; one of them, Hamilton Palace, was described by a Yelp reviewer as "Target after the apocalypse."

The former theater's 2,500-seat auditorium, located just behind this building, has been unused and decaying for some time. Here's a great photo tour of what the NY Times's Christopher Gray called "one of the most spectacular wrecks in New York City."

Built to house the 22nd Regiment of the Army Corps of Engineers, this armory was completed in 1911, and began hosting track meets shortly thereafter. By the middle of the 20th century, it had become "the cathedral of indoor high school track in the region", with an aging wooden running surface infamous for the generously sized splinters it would embed in the legs of any racer unfortunate enough to trip and fall during competition. (Here are one runner's recollections of those days.)

In the mid-1980s, the city decided to close the track and turn the armory into a vast homeless shelter that at times held up to 1,200 men. The place became notorious for its violence, drugs, and squalor, and was shut down several years later. The track reopened in 1993, this time boasting a new Olympic-style synthetic surface, and has once again become a "runners' mecca". The armory's stature in the world of athletics was given another boost in 2004, when it was dedicated as the new home of the National Track and Field Hall of Fame.

beneath the tangle of ramps leading to and from the George Washington Bridge