This is the hood ornament of a Soviet-made 1958 Волга ГАЗ-21 (Volga GAZ-21). Here's a shot of the whole car, and here's one of the dashboard (note the Cyrillic characters).

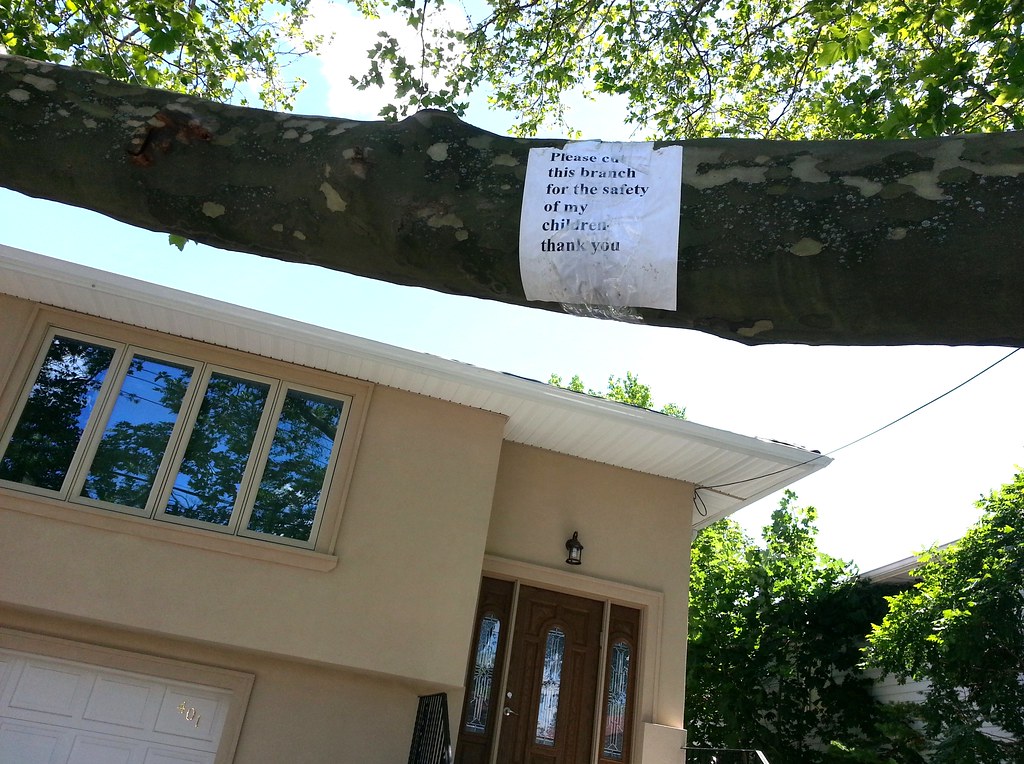

This 7,000-square-foot monstrosity, with its "cruise-ship-meets-mob-mansion" aesthetic, was built by Anthony "Gaspipe" Casso, a former underboss of the Lucchese crime family. (Casso subsequently had the house's architect murdered, fearing the man knew too much about his illegal activities.)

The Turano family (a mother and her two gynecologist sons) later took up residence here, purchasing and extensively renovating the house (hey, somebody had to repair the holes punched in the walls by FBI agents looking for bodies) with a boatload of dirty money from their intimate companion Carl Kruger, a currently imprisoned former state senator who spent much of his time with them here in "the most unconventional of domestic arrangements — at once public and opaque, widely whispered about and poorly understood."

This is the street entrance to the walled-off waterfront patio at the Gaspipe-Turano-Kruger house. You can see an aerial image of the house and patio here.

This is one of a few pedestrian passages that cut across the streets of Mill Basin, some more charming than others.

I think they may have been out of use for a while, but they certainly looked a lot better before Hurricane Sandy hit.

This is a delivery vehicle for the Mill Basin Deli, honoree of New York State Senate Resolution J576-2011.

Just about every component of this mikveh has been visibly sponsored by someone or another.

It'll still be a while before they're ready to eat; last year's fig bonanza reached full force in late August.

This is the self-proclaimed largest affiliate of Hatzoloh/Hatzolah/Hatzalah, the Jewish organization that is itself the largest volunteer ambulance service in the nation (and maybe the world). As was the case with the mikveh a few photos back, this building is laden with dedication plaques — there's one mounted on every single pillar and doorway on the first floor.

Here's what a spam commenter on a site called StreetAdvisor has to say about this dead-end dirt road remnant of an old colonial highway:

Lotts Lane is filled with places to shop and a few places to eat. A busier street than others in the area, Lotts Lane is definitely a good one to consider if you’re thinking of moving to Brooklyn. Mainly because of the wonderful people, accessibility to the metro and buses, and a general neighborhood feel, Lotts Lane is a great place to live, work, or leisure

According to the Parks Department, this house is "one of fourteen remaining Dutch Colonial farmhouses in Kings County. . . . The house remains structurally sound and virtually unchanged from the time Hendrick Lott constructed it in 1800, incorporating a section of the 1720 homestead built by his grandfather, Johannes Lott."

A sign posted nearby says that the grounds are currently being restored "to evoke the Lott family's farmstead landscape . . . [including] a vegetable garden, orchard, hedgerow, windbreak, ornamental plantings, a portion of the farm drive, an outhouse and a wellhouse." You can see the landscape plan here.

According to the Parks Department, the first tide-powered mill in North America was built here on Gerritsen Creek in the mid-1600s by Hugh Gerritsen. It stood on the far side of the creek, and wooden pilings from its dam are still visible at low tide. (I initially thought the pilings in this photo were remnants of the dam, but that's not the case, as pointed out in the comments below. This 1924 aerial image clearly shows the dam located a few hundred feet south of here.) It's said that the mill supplied George Washington's troops with flour during the Revolutionary War, and that it was also captured and used by Hessian troops fighting for the British. It remained in operation until 1889, and was still standing as recently as 1935, when it was burned down by vandals. You can see photos of the mill in its later days here and here.

The initial piece of what is now Marine Park was donated to the city as parkland by Frederic B. Pratt and Alfred Tredway White in an attempt to preserve the area's marshlands in the face of the totally crazy (in hindsight, at least) plans that were afoot in the early 20th century to turn Jamaica Bay into "the world’s largest deep-water port". Work on the harbor project actually commenced in 1912 with the dredging of Rockaway Inlet, but things petered out after that. To get a sense of how dramatically this development would have changed the city, compare this wild bird's-eye illustration of the proposed harbor (including a canal connecting Jamaica Bay and Flushing Bay) with an aerial image of today's Jamaica Bay.