is the old inert storage building (take a look inside) at Floyd Bennett Field.

The self-proclaimed "world's most famous tree" features an ever-expanding arboreal constellation of stuffed animals arranged and maintained by Eugene Fellner, a retired city worker who traces the genesis of his collection back to July 2007:

It just kind of happened one day when a neighbor called me and said there was a stuffed tiger [the thing wearing sunglasses near the bottom of the photo (zoom in), in the middle of the trunk] around the corner . . . I picked it up right there, brought it home, and placed it in the tree. It was a long time before the second animal went up. People would walk by and admire the tiger. Sometimes it would scare them, and they would jump if it caught them off guard.Check out this awful video to see an interview with Mr. Fellner.

Heading back from Brooklyn on the subway after my walk, I passed by Masstransiscope, Bill Brand's spectacular, zoetrope-inspired work of art installed in 1980 on the remaining platform of the Fourth Avenue Line's abandoned Myrtle Avenue station. The series of 228 hand-painted images was most recently restored in 2013 after graffiti writers vandalized it while the subway system was shut down for Hurricane Sandy. You can view Masstransiscope from Manhattan-bound B and Q (and late-night D) trains; after your train leaves the DeKalb Avenue station, just gaze out a window on the right side and wait for the show to begin. It's rare to see the whole thing without the train slowing down and stopping in the tunnel approaching the Manhattan Bridge, but, as Mr. Brand says, that's part of the experience:

When I designed Masstransiscope . . . the trains even then always slowed down and stopped as they still do today. So, I designed that feature into the piece. I actually like that the illusion breaks down and you can see the slits and the static paintings behind them.

In other words, DON'T SIT HERE.

(Spotted in NoHo on the way to the Staten Island Ferry.)

A memorial to the life of Army Staff Sergeant Michael H. Ollis

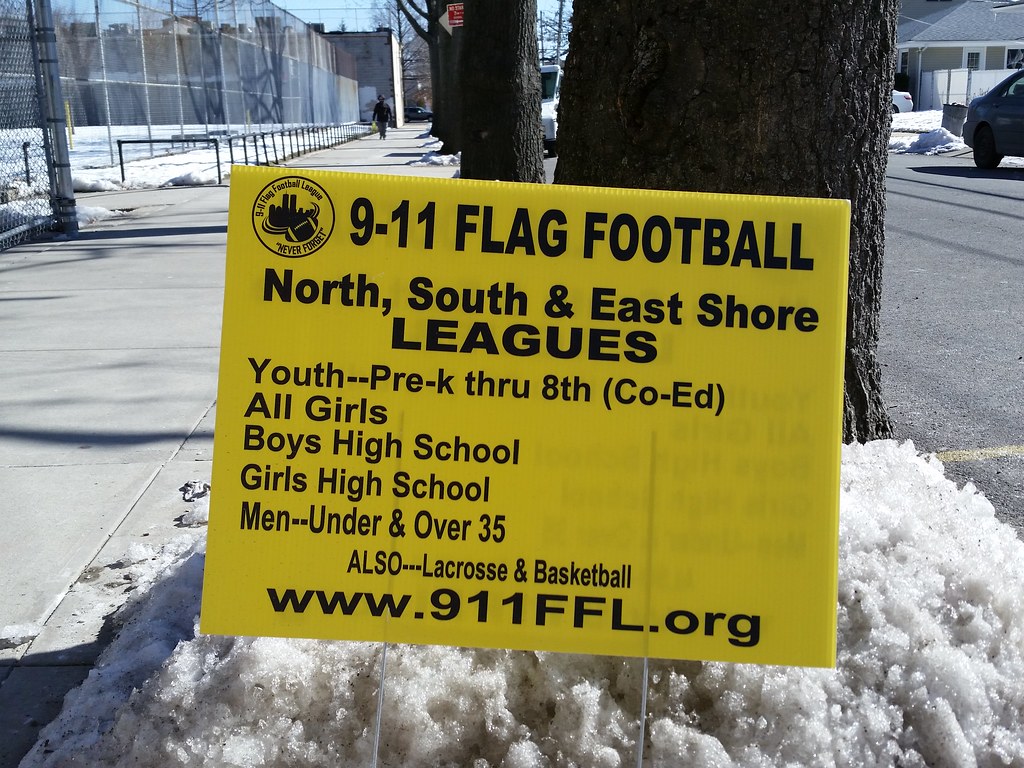

On 9/11, Stephen Siller, an off-duty firefighter, ran through the gridlocked Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel with some 60 pounds of gear on his back to reach ground zero, where he was killed. His namesake foundation organizes many fundraising events, including an annual 5k run through the tunnel to the World Trade Center.

Troy Restaurant: "How many excuse do you need to eat great food? Correct: none."

On the pole at right is one of NYC's relatively new speed cameras.

Here at the home of this grassroots relief organization, there's some familiar-looking container-top signage on display, including the Hurricane Sandy memorial at left. (And speaking of container tops, check out the scene here back in 2013.)

Standing outside St. Margaret Mary Roman Catholic Church in Midland Beach, this monument commemorates the seven neighborhood residents who lost their lives on 9/11. The memorial also includes a cross made from World Trade Center steel and another stone dedicated to neighborhood rescue and recovery workers who died from 9/11-related causes. The only person currently listed on that stone is Firefighter Lawrence Sullivan.

A 2014 winner of the Preservation League of Staten Island's Appreciation and Stewardship award

Padre Pio the stigmatic at St. Christopher's Roman Catholic Church

The patron saint of travelers at St. Christopher's Roman Catholic Church

Seriously! From the 1679 journal of two Dutch travelers who were visiting Staten Island:

We went on to the little creek to sit down and rest ourselves there, and to cool our feet, and then proceeded to the houses which constituted the Oude Dorp [Old Village]. . . . There were seven houses, but only three in which any body lived. The others were abandoned, and their owners had gone to live on better places on the island, because the ground around this village was worn out and barren, and also too limited for their use. We went into the first house which was inhabited by English, and there rested ourselves and ate, and inquired further after the road. The woman was cross, and her husband not much better. We had to pay here for what we ate, which we had not done before. We paid three guilders in zeewan, although we only drank water. We proceeded by a tolerably good road to the Nieuwe Dorp [New Village] . . . We saw a house at a distance to which we directed ourselves across the bushes. It was the first house of the Nieuwe Dorp. We found there an Englishman who could speak Dutch, and who received us very cordially into his house, where we had as good as he and his wife had. She was a Dutch woman from the Manhatans, who was glad to have us in her house.

While each of the other four boroughs is endowed with a vast profusion of numbered roadways, Staten Island can boast of only eleven such thoroughfares by my count (although there were once several more): 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th Streets here in New Dorp, and 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Courts in Annadale.

(If you look at a map of Staten Island, you may notice some numbered streets and avenues in the gated-off former tank farm area of Bloomfield [map] and on the old campus of the Willowbrook State School [map]. I'm not counting these roadways because they're not public streets and, as far as I know, they have no street signs indicating their names. You can also find a 19th Street in Annadale on Google Maps, but this block-long roadway is called Blue Heron Drive on its street sign and on the official city map as well.)

It seems unnecessarily confusing to give almost identical names to two consecutive parallel streets. Here's a similar situation we saw in the Bronx.

The intersection of Husson Street and Jefferson Avenue was named Patricia A. Kuras 9/11 Memorial Way in honor of Ms. Kuras, who was killed on 9/11. There are many streets and intersections that have been named for 9/11 heroes and victims; for the purposes of enumerating 9/11 memorials, I'm considering them all to be part of a single citywide memorial. But the plaque above, mounted on a house a few blocks away from the aforementioned intersection, seems to be someone's individual creation, and so I'll count it as a separate memorial.

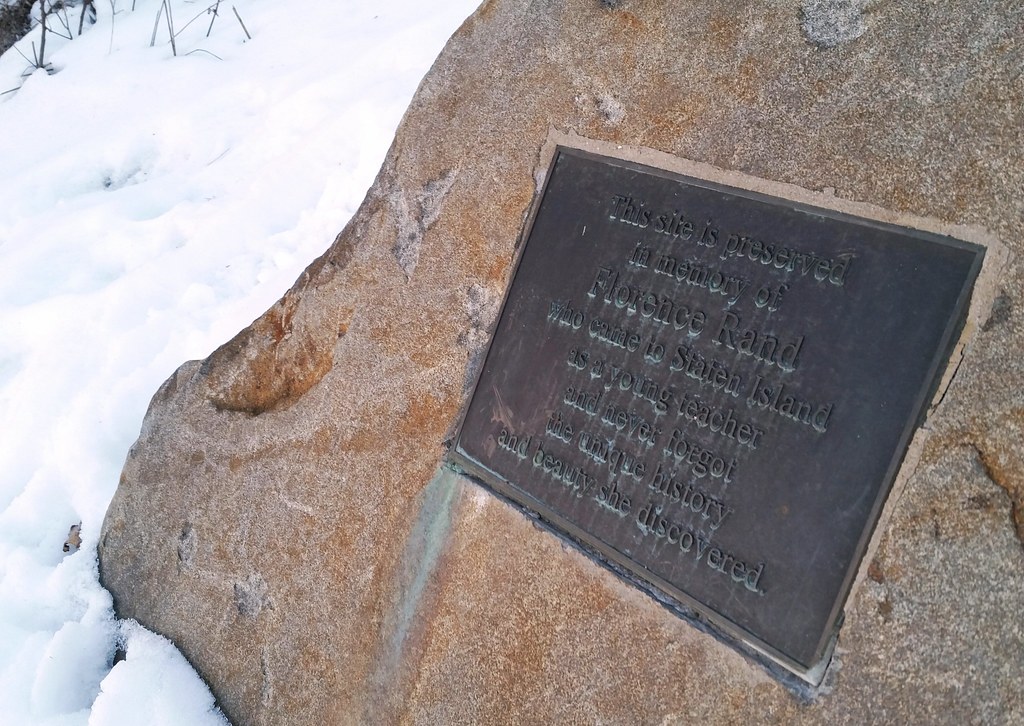

This plaque on a boulder in Last Chance Pond Park reads:

This site is preserved

in memory of

Florence Rand

who came to Staten Island

as a young teacher

and never forgot

the unique history

and beauty she discovered.

After taking the Staten Island Ferry back to Manhattan, I entered the South Ferry subway station and passed by this reconstructed portion of an 18th-century stone wall that was discovered nearby in Battery Park, along with two other such walls, during the construction of the current South Ferry station in 2005-06.

over the Clearview Expressway in Cunningham Park. Here's an aerial view.

Towering above its suburban surroundings, Building 40 is by far the largest structure on the grounds of the Creedmoor Psychiatric Center. (And it looks almost identical to the tallest building of the Manhattan Psychiatric Center on Wards Island.)

"A rich man's dream", the Long Island Motor Parkway (sometimes known by the flattering acronym LIMP) was "the first highway built exclusively for the automobile". Running 45 miles from eastern Queens to Lake Ronkonkoma in Suffolk County (annotated route map), this "quick and easy route for plutocrats of the Gold Coast era to get from New York City to their lavish Long Island estates" was conceived in the early 1900s, a time when the automobile was generally considered to be a plaything of the wealthy.

"Cars were seen as objects for leisure, something to be used on weekends", Paul Daniel Marriott, a highway historian, said in an interview with the NY Times. "No one dreamed then of commuting to work by car. . . . It was a way of interacting with nature."

Or, as Woodrow Wilson put it in 1906: "Nothing has spread Socialistic feeling in this country more than the use of automobiles. To the countryman they are a picture of arrogance of wealth with all its independence and carelessness."

One such wealthy individual was William Kissam Vanderbilt II, the great-grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt. According to the NY Times:

The younger Vanderbilt was a car enthusiast who loved to race. He had set a speed record of 92 miles an hour in 1904, the same year he created his own race, the Vanderbilt Cup.The first section of the parkway opened in 1908, and most of the rest was completed by 1912. (The westernmost two miles in Queens were built between 1924 and 1926.) The road's days as a racecourse were short and not so sweet, coming to an end after four people were killed during the 1910 Vanderbilt Cup race. A couple of decades later, with Robert Moses building free public parkways on Long Island in the midst of the Great Depression, the antiquated LIMP was pushed into financial insolvency, and it was shut down in 1938.

But his race came under fire after a spectator was killed in 1906, and Vanderbilt wanted a safe road on which to hold the race and on which other car lovers could hurl their new machines free of the dust common on roads made for horses. . . .

So he created a toll road for high-speed automobile travel. It was built of reinforced concrete, had banked turns, guard rails and, by building bridges, he eliminated intersections that would slow a driver down.

Moses, typically remembered for his car-centric approach to urban planning, quickly converted the westernmost two and a half miles of the parkway in Queens into a bicycle path. At the opening ceremony for the new path, with our old friend Mile-a-Minute Murphy in attendance, Moses announced that the path was the first trial section in a plan to build 50 miles of paved bike paths across the city.

Traces of the parkway can still be found along its former route. Here in NYC, the Queens bike path, pictured above, continues to preserve much of the road's right-of-way from Cunningham Park to Alley Pond Park. Physical remnants of the parkway can be spotted along the path, including "portions of the original concrete and asphalt surfaces, together with markers and fence posts", as well as three of the 1924-26 bridges that carry the path over intersecting roadways.

on the bike and pedestrian path that follows the former route of the Long Island Motor Parkway from Cunningham Park to Alley Pond Park

Checker stopped making cars in 1982, and the city's last Checker cab went out of service in 1999. This car appears to have actually been a taxi at some point, although maybe not in NYC.

New York Buddhist Vihara, a Sri Lankan Buddhist temple

Named after the North American Martyrs

The plaque reads:

American Martyrs

Remembers All Those Lost

September 11, 2001

Always In Our Prayers