Here on the private beach of Sea Gate, the gated community that occupies the western end of the Coney Island peninsula, the Army Corps of Engineers is at work on a $25.2 million shoreline protection project. Pictured above is the construction of one of four T-groins designed to prevent erosion of the beach, to which 125,000 cubic yards of sand will be added. The fact that federal funds are being used to build up a private beach has raised some eyebrows, but, according to the Army Corps,

the work is primarily benefitting the original Coney Island coastal storm risk reduction project that was first constructed in the 1990s. . . .

While the Sea Gate work will definitely provide some coastal storm risk benefits to the Sea Gate community, it will not be of the size and scope of the public beach originally constructed to the east of the W. 37th Street groin and the primary benefit of completing this important portion of the Coney Island project is reinforcing the integrity of the W. 37th Street groin which anchors the public beach.

This lighthouse at the western tip of Coney Island, in what is now the gated community of Sea Gate, was built in 1890. In 2003, the final lighthouse keeper to serve here, Frank Schubert (photos), passed away at the age of 88 in the adjacent cottage (at right), where he had lived since taking the job in 1960. Prior to his death, Coney Island Light was one of only two manned lighthouses remaining in the country, the other being the 1783 Boston Light, whose original 1716 incarnation was America's first lighthouse. Mr. Schubert was for some time the nation's last civilian lighthouse keeper — Boston Light had long been staffed by Coast Guard personnel — but a few months before he died, a civilian named Sally Snowman was hired as the keeper of Boston Light, becoming the first female ever to hold that position. And now that Mr. Schubert has passed away, she's the only lighthouse keeper left in the United States.

From left to right, the most prominent features are the Verrazano Bridge, the Brooklyn VA hospital, the Bay Ridge Towers, One World Trade Center and the skyline of Lower Manhattan, the Empire State Building, 432 Park Avenue, and a seagull. Here's a closer look.

Coney Island's Mark Twain Intermediate School (formerly Mark Twain Junior High School), a selective magnet school for gifted and talented students, is one of the city's top middle schools. Until 2008, it admitted students under a racial quota system mandated by a 1974 federal court ruling (this ruling also dictated that Mark Twain become a magnet school in the first place). But the quotas weren't part of an affirmative action program — they were originally intended to increase the number of white students at what had been a segregated school. Over the years, however, as the demographics of the school district shifted, the quotas had some unintended consequences. An NY Times article from February 2008 explains:

The original court order for Mark Twain Intermediate School was imposed when the region, District 21, was overwhelmingly white. The court held that the local school board was deliberately segregating that school by sending middle class white students elsewhere. The court ruled that the school should not have more than 10 percent more minority students than the districtwide average, which was about 30 percent.This lawsuit is what finally prompted the city to take legal action in 2008 to have the 1974 desegregation order lifted so that the quota system could be thrown out and a race-neutral admissions policy established going forward.

Over time, however, the neighborhood has changed and the proportion of white students has steadily decreased in the area’s middle schools, down to roughly 40 percent in 2007.

As a result, the court order has ended up leading Mark Twain, now a respected program for gifted students, to require higher scores on admissions tests for minority students than for white students. . . .

The parents of Nikita Rau, an 11-year-old whose family immigrated from India, filed a class action lawsuit last month against the Department of Education after Mark Twain rejected her last year. She scored a 79 on the school’s music admissions test — below the 84.4 required for minority students to be accepted, but above the 77 for white students.

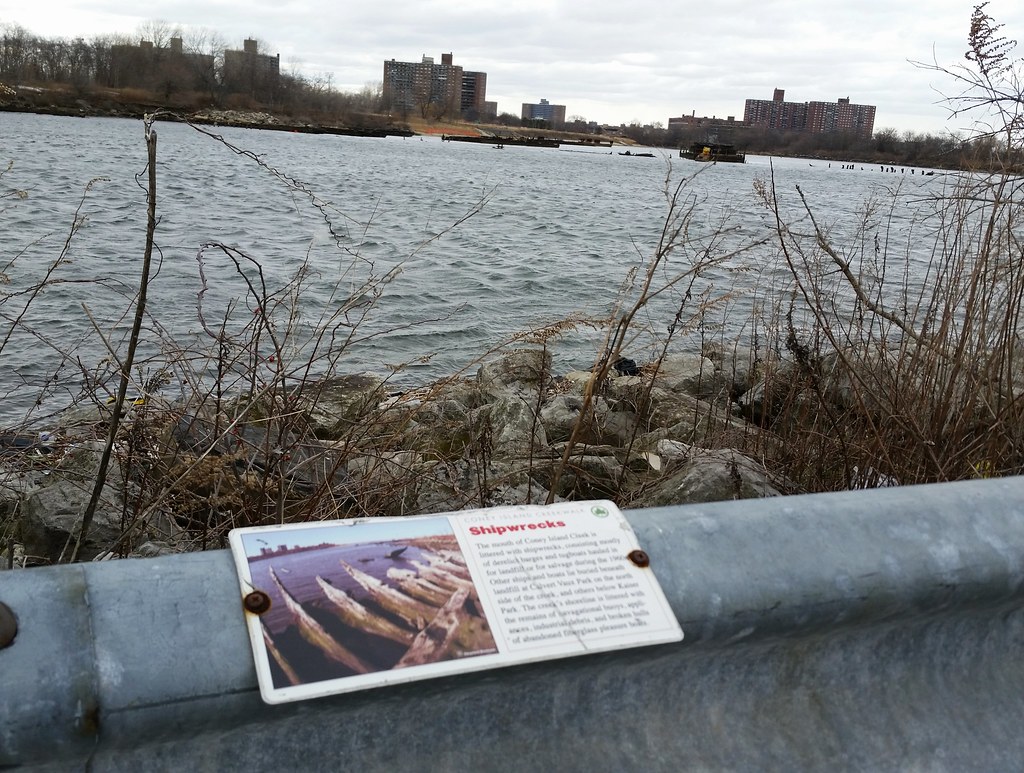

The placard above, part of Charles Denson's Coney Island Creekwalk, offers some information about the many boat carcasses lurking in the waters of Coney Island Creek, a few of which can be seen in the background of this photo. (A close inspection of aerial images reveals, by my count, around three dozen decaying vessels in the creek.) The most famous of the wrecks, which gets its own placard from Mr. Denson, is the Quester I (more info), a.k.a. the Yellow Submarine, built between 1966 and 1970 by a local man named Jerry Bianco who dreamed of using the sub to raise the Andrea Doria and recover all of the sunken ocean liner's treasures. The Quester I is visible above on the right side of the photo, its yellow conning tower set against the dark hulk of the rotting barge that lies right behind it. Here's a closer look.

Not Ray's — fittingly, not the first time someone's come up with that joke.

Inside the box at left (close-up) is a memorial to Jeffrey Martinez.

(Fangz is someone else. "—R.I.P— FANGZ" was painted before Mr. Martinez died.)

At the Engine 318/Ladder 166 firehouse. In its current condition, it's hard to tell that the drawing above is 9/11-related, but if you look closely you can see what appears to be a piece of the twin towers' shattered facades in the upper left corner.

Jason "Juice" Sowell. Here are a couple of photos of basketball star Stephon Marbury visiting this memorial to his friend and Lincoln High School teammate. You can see the extended mural in Street View.

Site of the famous photoshoot for the cover of the album "123 Fake Street" by Coney Island's twin quasars of rock, King Par and the Only Permit.

Now the abandoned centerpiece of a community garden, the Irwin Chanin-designed 1938 Coney Island Pumping Station was built to maintain constant water pressure in the area for fighting fires. Check out this old photo: where there's now just a painted cinder block wall, a three-tier band of windows once ran horizontally around the building (interior photos). The double Pegasus sculptures that once flanked the entrances were vandalized around 1980 and were subsequently moved to the Brooklyn Museum's sculpture garden in 1981.

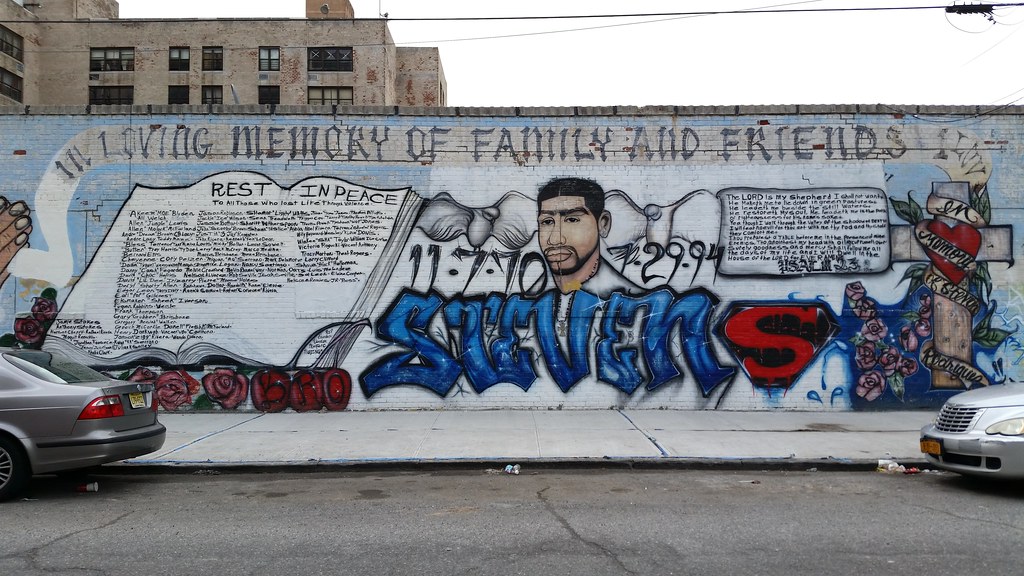

of Steven Rodriguez and "all those who lost life through violence" (listed in the book at left)

The original! When I passed this barbershop on a walk in Coney Island one evening back in 2009, I was astounded by the sheer number of Zs on the sign, not to mention the K-for-a-C and the missing H: FADERZ — KUTZ WIT SKILLZ. The name burned itself into my brain and eventually led me, a couple of years later when I started this five-borough walk, to decide to keep a tally of all the barbershops whose names feature a Z in lieu of an S.

I couldn't remember exactly where Faderz was located, however, and I was worried it might have gone under by now — so I was ecstatic to find it still in business after all these years!

Looking out over Coney Island Creek toward the Verrazano Bridge

This former Rubel Coal & Ice building is now a Sanitation garage. As we learned back in 2012 (and again in 2013):

The tale of Samuel Rubel exemplifies the classic American rags-to-riches story: Penniless Latvian immigrant arrives on the streets of New York; builds multi-million-dollar coal-and-ice empire from meager beginnings as a door-to-door peddler; proposes to employee, then later breaks off the engagement; she sues him; he has her arrested on charges of forgery and grand larceny; they later get married, have two kids, and live happily ever after.

The basketball hoop was added after the building lost its footing.

Established in 1995. Santos told me he and his band, the Romantics, sometimes perform on stage here.

(The cow is fake, but the ducks are real. Take a closer look.)

Built around 1923, this "colorful terra cotta and stucco homage to the sea" (photos — scroll down a little) was originally a Childs Restaurant. Childs was a quick-lunch chain founded in 1889; by the mid-1920s, it had more than 100 locations, about half of them in the New York area. (Sideshows by the Seashore currently occupies another old Coney Island Childs. Check out these photos of other former Childs eateries around the city.)

After the restaurant here on the boardwalk closed, the building served as a candy factory for the latter half of the 20th century, and as a roller rink for a couple of years in the 21st. Work is now underway to turn the place into the Seaside Park and Community Arts Center, which will feature a 5,100-seat amphitheater, a restaurant, and a public park. (A rendering of the new facility posted on the construction fence above includes a couple taking a flip-phone selfie!)

This public transfer high school is housed in what used to be the school of Our Lady of Solace.

UPDATE: Great NY Times article from Sept. 9, 2016: "Minority Youths Mistrust Police. A Brooklyn High School Has a Plan."

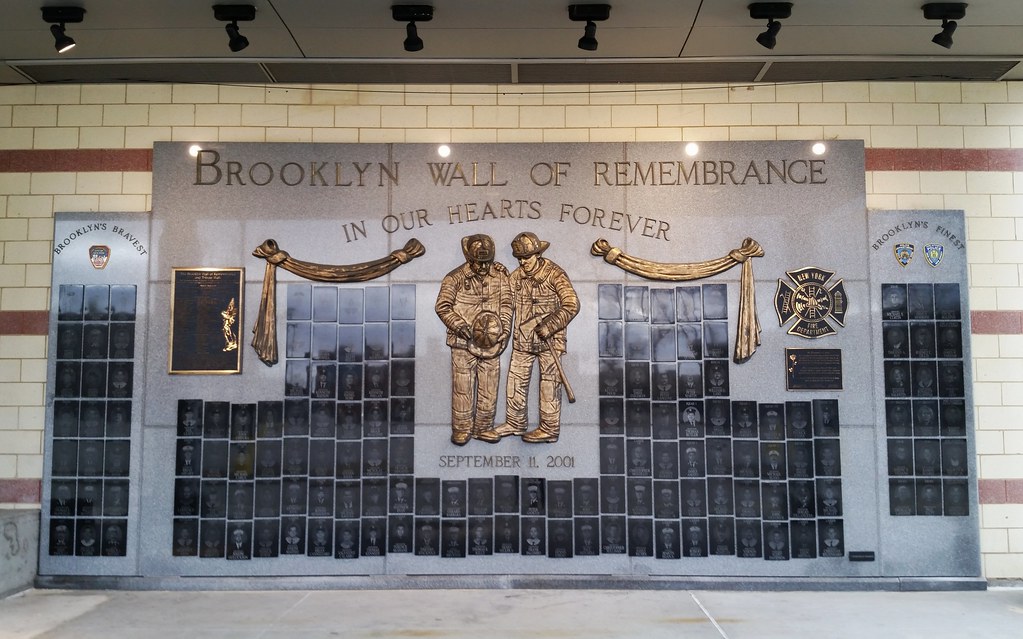

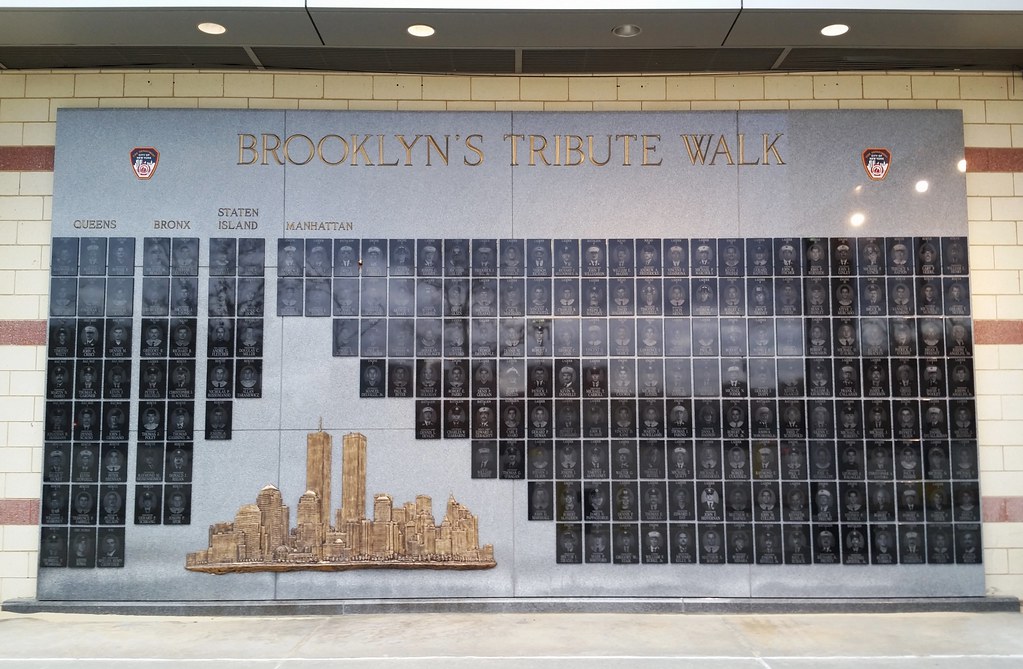

Located at the Brooklyn Cyclones' ballpark, the Brooklyn Wall of Remembrance pays tribute to all the first responders killed on 9/11.

Redesigned and reopened since being damaged by Hurricane Sandy. Here's how it used to look.

at this standpipe connection, used for fighting fires on Steeplechase Pier. (That's the Parachute Jump lit up in the background.)

This monument outside the Brooklyn Cyclones' stadium commemorates a storied moment in baseball history — when Pee Wee Reese stood in solidarity with his teammate Jackie Robinson against a barrage of racist taunts being hurled at Robinson by opposing fans — although the version of events presented on the monument probably isn't entirely accurate.