Mike Tyson spent a fair amount of time inside these walls during his delinquent youth in Brownsville.

The sign on the building reads "65 Precinct" — at some point, the 65th was changed to the 73rd Precinct, I believe in the 1920s.

The Canarsie Line and the Bay Ridge Branch, respectively

Walking through East New York today, I found myself immersed in a lengthy conversation with a Rasta named Bent. He had called out to me from across the street simply because he didn't recognize me. I thought that was kind of odd (isn't a city as big as New York bound to be full of strangers?), but then he did seem to know every single one of the people who happened to pass by during the course of our conversation. Wearing a button with the image of Haile Selassie, Bent mostly spoke to me about Ethiopia, with topics ranging from Amharic and Ge'ez to Beta Israel to the connections between Ethiopia and India.

He also talked about moving to East New York in the mid-'90s, when his house was the only thing standing on this side of the block (the adjacent lots were vacant garbage dumps). Many of his neighbors were saying they wanted to move somewhere safer and nicer, but he told me you shouldn't flee to a better neighborhood; you should make your own neighborhood better. He's spent a lot of time turning around his corner of the world: among other things, he's planted several trees out on the street, including the ones you see here. I wasn't sure our conversation was going to end before nightfall, but then Bent suddenly excused himself, saying he had to go because he is "on a mission." His parting words to me: "One love, one heart."

(He didn't want me to take his picture, which is a shame because his outfit perfectly matched the red, yellow, and green painted on his house.)

Actually, the L train runs on the left-hand side of this structure. The portion I'm standing under used to support the elevated Fulton Street Line.

This underpass takes you to the East New York LIRR station on the Atlantic Branch, which you can see just across the road (the outer lane of Atlantic Avenue), beneath the arches that support the elevated center lanes of Atlantic Avenue. The Atlantic Branch, which runs underground on either side of this station, rises to street level here to allow another rail line, the Bay Ridge Branch, to pass beneath it. As if that weren't enough, you can also see the elevated tracks of the Canarsie Line (L train), which cross Atlantic Avenue just to the left of this photo (where the previous photo was taken), in the background. Take a look at a bird's-eye view to get a better sense of the area. (Things don't get any simpler at Broadway Junction, just north of here.)

As mentioned previously, this enormous building is currently a homeless shelter. But what was its original purpose? According to the New York Times:

After the Civil War, a number of armories were built around the city to assuage the fears of middle- and upper-class New Yorkers who had seen Civil War draft riots and the Tompkins Square Riots of 1873. A growing immigrant population and a depression begun by the panic of 1873 fueled concern over unrest. Between 1880 and 1913, New York and Brooklyn sponsored the construction of 29 armories, including the Bedford-Atlantic Armory, built for the 23rd Regiment in Brooklyn.

The armory was designed by Isaac G. Perry, chief architect of the State Capitol in Albany. Construction began in 1889 and was completed in 1902 on a building whose 50,000-square-foot drill hall provided open space for training recruits. The vast space also allowed for functions like dances and dog shows.

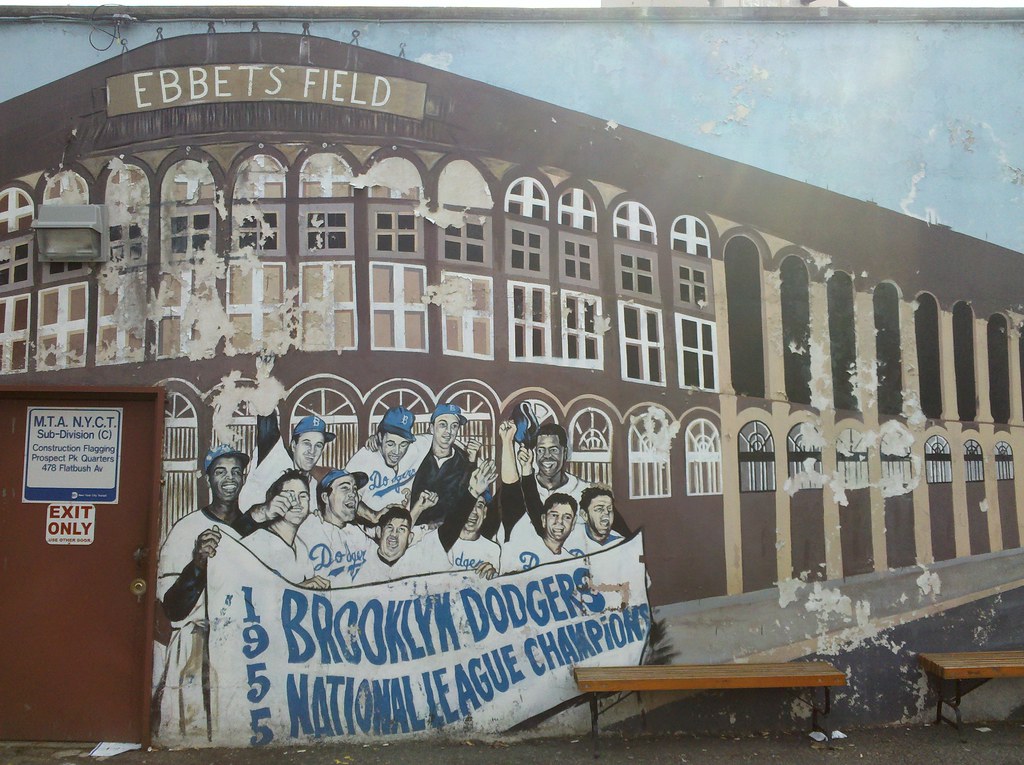

Located right across the street from the former Ebbets Field. The park superintendent told me that one day last year he saw a Jehovah's Witness carrying a copy of The Watchtower with a beautiful painting of sea creatures on its cover. He found out who the artist was and asked him to replicate the painting, on a much larger scale, in the playground. It looks beautiful, but there turned out to be a problem: he used the wrong kind of paint, and now the surface becomes really slippery when it gets wet. The super said he'll have to figure out a solution before summer, when the bears start shooting water out of their mouths.

I liked it until I read the description on that blue sign over there: "Lincoln Road Serape is a 70-foot weaving made of plastic ribbons woven into the chain link fence to create a colorful swathe that connects the neighborhood. The installation is based on weaving blanket designs of diamond shapes and zig-zags woven by Navajo craftspeople."

To be fair to the artist, she doesn't use any of that language on her website, leading me to believe this may be another case of terrible DOT writing.

I'm feeling pretty good about my previous guess.

It's a pretty good imitation of the original (especially the original original).

P.S. This building is located on a two-block-long street named Tennis Court, which once ran through an enclave of houses called Tennis Court, and which still leads to some actual tennis courts at the Knickerbocker Field Club. The Knick, established in 1889, is largely hidden from the street, tucked out of sight behind three large 20th-century apartment buildings.

That's the colloquial name for this chunk of central Brooklyn, which was "in many respects . . . the first suburbs." This particular house is located in the neighborhood of Beverley Square East.

Funny note about the linked NY Times article: it mentions the hideous abbreviation "NoProPaSo" (North of Prospect Park South), which for years I had cited as the most heinous of the recent rash of shortened neighborhood nicknames. Turns out it was created as a joke, but the Times reporter failed to record that detail!

Unlike the extensive Manhattan Eruv, this one just encloses a few neighboring houses.

Located here on Waldorf Court and a block south on Wellington Court, these unusual traffic calming medians are rather unobtrusive.

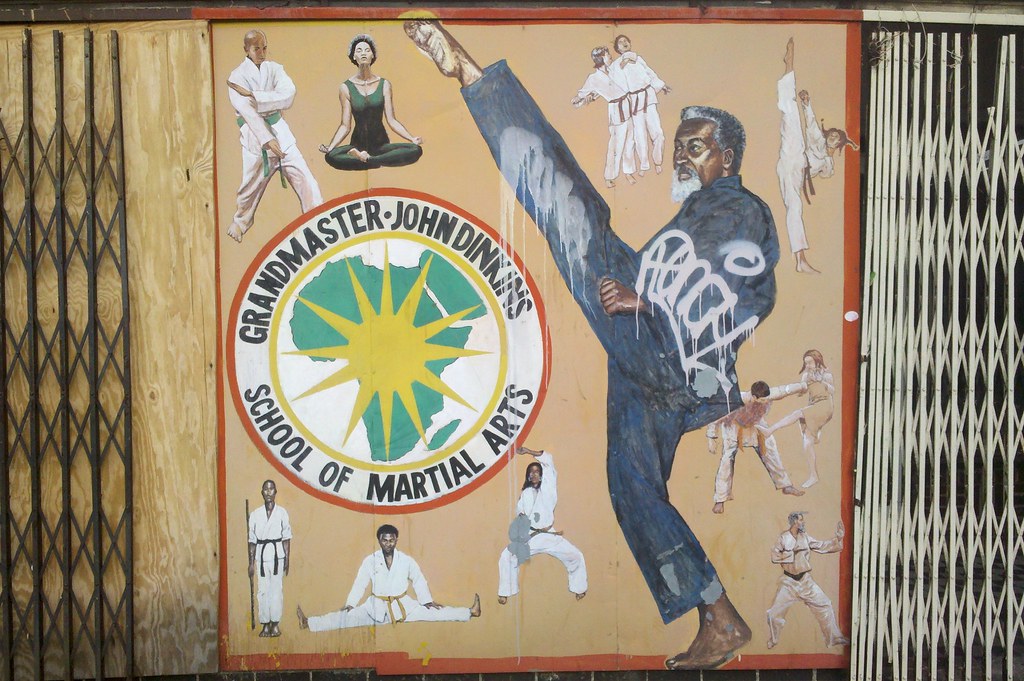

from the soaring foot of Grand Master John Dinkins.

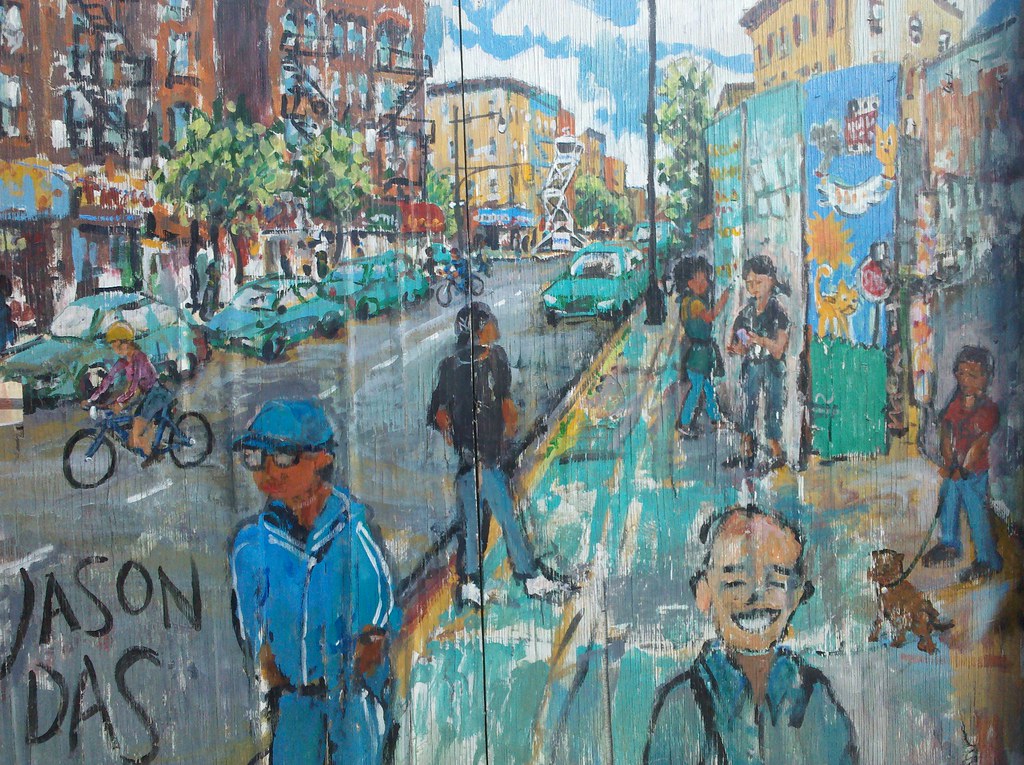

As depicted on a construction wall mural. You can see a SkyWatch tower in this mural (three in three days!). You can even see the construction wall in this mural. In fact, you can see this mural in this mural! (It's the one all the way to the right, next to the dog-and-cat panel.) The artist cut off the right side of the mural-within-the-mural, however, eliminating the need to paint an infinite regress. Check it all out on Street View.

UPDATE: This mural is even cooler than I thought!

Sort of!

Outlawed by the state in 1975, an exception for their use in NYC was granted after a 1990 lawsuit. Starting in 1992, and continuing for the next 16 years, the city repeatedly tried and failed to move beyond the testing phase of various toilet proposals. By 1994, after a mere two years, the NY Times was already fed up:

"The city's frustrated attempts to meet the basic human need for a safe, clean place to go to the bathroom exemplify how cumbersome governmental processes, flawed planning and a cacophony of competing interest groups can delay the achievement of a common-sense goal."

Finally, in 2008, it was all figured out. The first post-1975 permanent pay toilet was installed in Madison Square Park to much fanfare, with the promise that 19 more would soon be in place around the five boroughs. (Here's a review of that toilet, for those curious about the workings of an automated commode.)

However, by late 2010, there had only been one additional toilet installed (in Corona Plaza, Queens). But after more than a year of wrangling, work was finally underway on a third location, here at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn.

So now it's 2012, and we have a grand total of three pay toilets to show for two decades of bureaucratic maneuverings. (I assume there are still only three: the city's own website lists just the first two.)

Finally, it should be noted that these machines consume a monstrous 14 gallons of water per use! Perhaps it's for the best that they remain so few and far between.

A policeman and a scholar. (Pardon the overly gushing tone of this link; it's the only writing of substance I can find about the man.)

This park is named after Umma (an Arabic word meaning "community"), a highly successful community group formed in 1978 to help fight crime in the neighborhood. A local blog recently published a lengthy interview with Ed Powell, one of the founders of Umma.

Founded in 1654 under the direction of everybody's favorite peg-legged, intolerant bastard (but then again, who wasn't in those days?) (these guys weren't!) (intolerant, that is, not peg-legged) (although odds are they weren't peg-legged either), Peter Stuyvesant.

The oldest legible stone here in the cemetery apparently dates to 1754; I saw several from that era (1760s and 1770s) during my brief stroll. While some of the markers are now too worn to be read, others have achieved unintelligibility simply by sinking into the ground over time, their recorded dates of death themselves becoming interred.

For an unusual take on this place, I'd recommend the beautiful photos and fevered narration of Mitch Waxman, who can generally be counted on for such things.

Erasmus was founded by Dutch settlers in 1786, and the original Academy building is still standing in the courtyard (you can just catch a glimpse of it through the gated entryway) of the grand, Gothic-style campus that was built after Erasmus was donated to the public school system. The building pictured here was the first part of that campus to be constructed, and it was opened in 1906.

If this photo looks familiar to you, it's because both schools were designed by Charles B.J. Snyder during his prolific tenure as NYC's Superintendent of School Buildings from 1891 to 1923. His lofty ideals for municipal architecture revolutionized the school system and "symbolized the commitment of the city to care for and even uplift its citizens", according to the NY Times.

(As you may recall, I passed by the backside of Erasmus on Bedford Avenue last month.)

He's memorializing all the people who died in the earthquake, fire, and famine of 1805!

About 30 feet to the right of this door, a bright red, wall-length mural boldly proclaims: "Everybody was born talented / So find your talent / And don't waste your talent". Mission accomplished.

The Q train station at Avenue H was not originally built as a train station: it was a real estate office for T.B. Ackerson, one of the developers of Victorian Flatbush. Landmarked in 2004, it's one of the few remaining wood-frame station houses in the subway system. It is so quaint, in fact, that its porch roof is held up with honest-to-goodness log columns. Which, of course, raises the question: Why are there no rocking chairs??

I was surprised to find this battery of NYPD security cameras guarding the quiet terminus of a leafy dead-end street here in Victorian Flatbush. One resident who was out walking his dogs told me they were installed as a response to people hopping the fence and walking along the subway tracks to the nearby station (less than a block from the right edge of this photo), thus avoiding paying the fare. While that explanation didn't seem totally implausible, it also didn't pass the smell test: the two directional cameras were both pointed away from the area where people would be climbing over the fence. In fact, they seemed to be rather conspicuously monitoring a house on the left side of the street. Further research reveals the real reason those cameras are there: that house is occupied by the NYPD's highly decorated Chief of Department!