Covering pavement sealant with pages from a grocery store circular? I mean, come on. Everyone nowadays knows toilet paper is the way to go.

A Scientology chapel and community center are coming to East 125th Street. The multimillion-dollar facilities will be located in the renovated building above and in a new structure now rising two doors down. As you can see in Street View, the two buildings will be separated by a branch of the New York Public Library.

I got out here at morning rush hour this time, but Otis was still nowhere to be found.

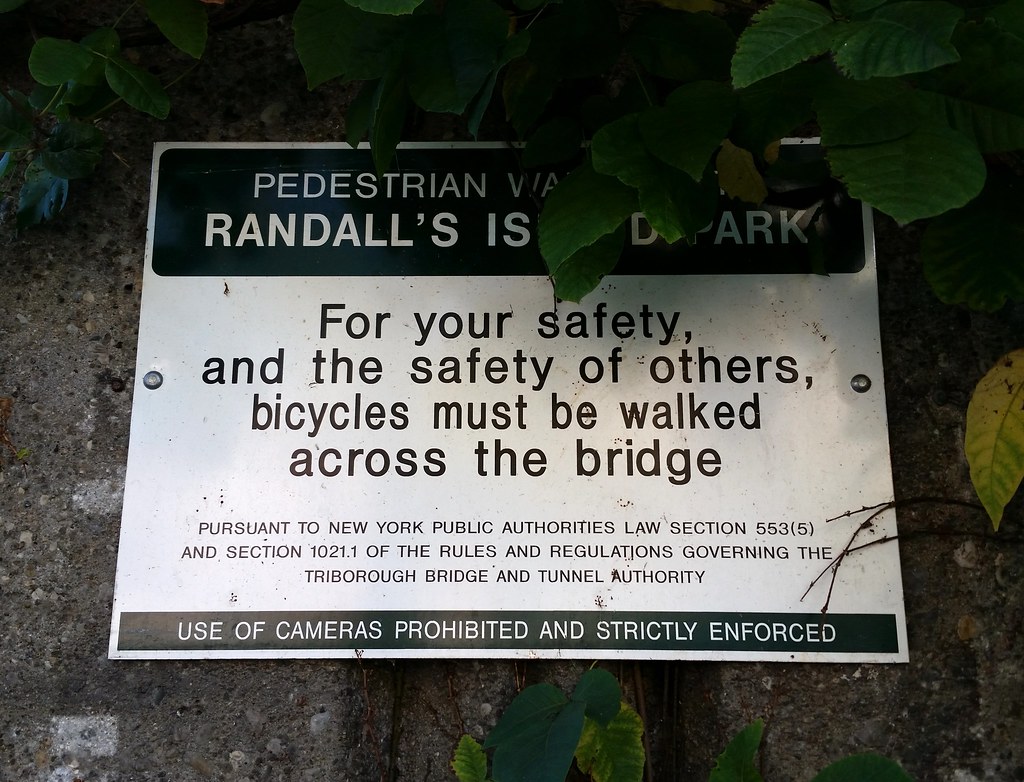

Robert Moses's former Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority headquarters, located on Randall's Island near the Triborough's Manhattan toll plaza, is one of the very few things in NYC named for the controversial master builder who reigned over the city's (and the state's) infrastructure for decades. The man has several namesakes elsewhere in the state, but I know of only two others in NYC.

The Triborough Bridge (officially known as the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge) is actually composed of three separate bridges that connect the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens; the three bridges meet on the conjoined Randall's and Wards Islands. The bridge above, spanning the Harlem River, is the Manhattan leg of the triad.

This statue, originally known as Discobole Finlandais, won the gold medal in the sculpture competition at the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris.

From the Parks Department's website:

From the [Hell Gate Bridge] proper stems the viaduct – a long arcade of . . . high Romanesque arches made of sandy-colored concrete, recalling the form and grand march of a Roman aqueduct. The route beneath the arcade has been converted to the new Hell Gate Pathway, a dedicated pedestrian and bike path that runs through the monumental arcade, connecting to the larger waterfront pathway system that circles [Randall's and Wards Islands].

You're looking at two of the four inverted bowstring truss spans that formerly carried the Hell Gate viaduct across Little Hell Gate, the now filled-in channel that once separated Randall's and Wards Islands. To get a sense of how the islands have changed over the years, compare these aerial images from 1924, 1951, and 2012.

Named after corporate raider Carl Icahn, this track and field stadium on Randall's Island opened in 2005 and has already had a world record set here, by Usain Bolt in the 100 meters in 2008. The stadium was built in place of the demolished Downing Stadium, which had seen its own share of notable events over the decades, starting with Jesse Owens qualifying for the 1936 Olympics on the night it opened. (Wearing Ohio State colors, he "flashed over the Randalls Island Stadium cinders like a scarlet comet", according to the next day's NY Times.)

Ebbets Field, the beloved former home of the dear departed Brooklyn Dodgers, was knocked down in 1960, and its lights were later installed at Downing Stadium. I've read that Downing's lights were reused here at Icahn, but I can't find any reliable source for that claim. Even if they were reused, it sounds like most of the original Ebbets lights had been replaced by the time Downing was demolished.

The Little Hell Gate Inlet is all that remains of the channel that once separated Randall's and Wards Islands. (To get a sense of how the islands have changed over the years, compare these aerial images from 1924, 1951, and 2012.) The eastern half of the inlet has been restored as the "fully functional salt marsh" you see above. The footbridge in the center of the photo, spanning the inlet, is part of a recreational path that passes through the marsh.

If you've been wondering why Randall's Island has an apostrophe in its name and Wards Island doesn't, I don't have a great answer for you. Both islands are named after former owners, so it seems apostrophes would be in order in both cases to indicate that the names are possessive. But possessive apostrophes have long been frowned upon by the US Board on Geographic Names, setting an oft-followed precedent for their removal from place names across the country. NYC is inconsistent with its apostrophes (although you'll almost never see one in a street name), and you can find both Randall's and Wards Islands written with and without apostrophes on different city signs and maps. But for some reason, the city government is more often than not inclined to include the apostrophe in Randall's and omit it from Wards. (See, for example, Randall's Island Park and Wards Island Park.)

That's the Manhattan Psychiatric Center up ahead. As far as I know, the only people who live on Randall's and Wards Islands are the residents of the psychiatric hospitals and homeless shelters. (The islands' population was listed in the 2010 census as 1,648 people in zero households.)

The islands mostly consist of athletic fields and other parkland, but they're also home to a wastewater treatment plant, the city's fire academy (photos, photos), a state police troop headquarters, the Triborough Bridge toll plazas, and MTA Bridges and Tunnels administrative offices.

The most eye-catching part of the Triborough complex, this suspension bridge connects Queens and Wards Island over the Hell Gate channel of the East River. And speaking of eye-catching, the behemoth at right is Astoria's Shore Towers.

The Hell Gate Bridge, seen here from the native plant garden in Wards Island Park, was painted a deep red in the 1990s. But the paint was defective and started fading before the job was even complete, leaving the bridge with the pale, patchy appearance it still boasts today.

Overlooking a nearby baseball field, this sculpture "translate[s] the vernacular of the baseball backstop into an ethereal and slightly surreal contemplation of the American home."

In 2001, an NY Times reporter informed Henry Stern, the city's parks commissioner at the time, that the southern tip of Wards Island, in Wards Island Park, was labeled Negro Point on official nautical charts. Seeing the obscure name as unnecessarily offensive, Mr. Stern — known to be a fan of playful and unusual appellations — suggested to the US Board on Geographic Names that Negro Point be rechristened Scylla Point as a complement to Astoria Park's Charybdis Playground — named by Mr. Stern a few years earlier — which sits just on the other side of the turbulent and formerly very treacherous Hell Gate channel. (Scylla and Charybdis were mythical monsters who lived on either side of a narrow strait, making it very perilous for ships to pass through.)

The executive secretary of the board seemed receptive to the idea, but the latest NOAA nautical charts and USGS topo maps still say Negro Point (although Google Maps says Scylla Point). While Mr. Stern may have wielded no authority over federal map labels, he did have the power to name city parks and playgrounds just about anything he wanted; hence, I would imagine, the playground above, located just a few hundred yards from the disputed piece of land.

at the Randall's Island Urban Farm (photos), which recently acquired a bicycle-powered huller to process the harvests of "all five of New York City’s rice paddies".

(Despite the name, the farm is actually located on the Wards Island part of Randall's and Wards Islands. But the Randall’s Island Park Alliance refers to the conjoined islands collectively as Randall's Island.)

This is part of the Project EATS farm (photos) at the Help USA Supportive Employment Center, a homeless shelter that provides its residents with vocational training. Some of the produce grown here is sold to restaurants and Fresh Direct, with the proceeds used to subsidize affordably priced farm stands in low-income and working-class neighborhoods. Food from this farm is also used in the employment center's cafeteria and in its culinary arts training program.

This standpipe allows water to be pumped up to the viaduct in case of a fire.

Some classic barf-inducing artspeak: "To install Ground, Sanders created ten sculpted earth chairs, in a variety of forms . . . The installation offers an unmitigated phenomenological experience, the opportunity to interact with a living material in a simultaneously nostalgic and atypical way."

Heading over the Wards Island Bridge to the island's athletic fields

This island in the East River started out as two smaller islands: Great Mill Rock and Little Mill Rock. According to The Other Islands of New York City:

Great Mill Rock was first developed between 1701 and 1707, when John Marsh built the tidal mill there that gave both the islands their names. During the War of 1812, the army built a blockhouse with cannons on the island to deter the British from making their way from Long Island Sound. The blockhouse burned down in 1821. In 1850, John Clark claimed squatter's rights to Great Mill Rock and began selling food and booze to passing boats. A decade later, he sold the island for $40 to Sandy Gibson, who moved his entire household there, right down to the cows and chickens. Three years later, Gibson sold the land to a Charles Leland for $300, but stayed on for several more years as a tenant, catching eels and flounder for food.The Mill Rocks sat amid many other rocks, reefs, and islets with some colorful names among them: Hen and Chickens, Hog's Back, Frying Pan, Bread and Cheese, and Bald-headed Billy. These riverine obstacles made the churning waters in and around Hell Gate notoriously treacherous to navigate. In 1851, the Army Corps of Engineers began a long campaign of blasting these dangerous obstructions out of existence.

October 10, 1885 saw the annihilation of nine-acre Flood Rock by nearly 300,000 pounds of explosives, much of which had been prepared at a facility on Great Mill Rock. "The largest planned explosion prior to the atomic bomb" (a debatable claim), it was reportedly felt about 50 miles away in Princeton, New Jersey. The event was a huge public spectacle, covered extensively in the NY Times. Some excerpts:

The cross streets east of the upper end of Central Park were full of people moving toward the East River. Down town great numbers of people were climbing to the tops of high buildings, for they were sure that they would hear the thunder of the explosion and see the huge sheets of water shooting into the air. All along the East River front every "coign of vantage" was pre-empted early in the day.Check out this photo of the explosion!

The bulk of the crowd, however, assembled on the sides of the abrupt slopes that descend to the river . . . opposite the scene of the explosion. Men, women, children, dogs, and goats mingled in one broad, variegated mass. . . . Hundreds of people gathered on the tops of the big breweries and other tall buildings that loom one above another on the easterly decline of the city. Away up on the tops of chimneys and on the outermost pinnacles of roofs could be seen the irrepressible, never-to-be-left small boy, filled with the American instinct for getting to the top and looking down on the whole business. Trees had their usual load of sightseers and lamp posts were opportunities to be embraced with avidity. Down along the water's edge the masses concentrated into a solid, sinuous wall that wound around among the piers and wharves as far as the eye could reach to north and south. . . .

[Upon the detonation of the explosives by the young daughter of the general in charge of the project:] Away it flew, that viewless spark, to loose three hundred thousand chained demons buried in darkness and the cold, salt waves under the iron rocks. A deep rumble, then a dull boom, like the smothered bursting of a hundred mighty guns far away beyond the blue horizon, rolled across the yellow river. Up, up, and still up into the frightened air soared a great, ghastly, writhing wall of white and silver and gray. Fifty gigantic geysers, linked together by shivering, twisting masses of spray, soared upward, their shining pinnacles, with dome-like summits, looming like shattered floods of molten silver against the azure sky. Three magnificent monuments of solid water sprang far above the rest of the mass, the most westerly of them still rising after all else had begun to fall, till it towered nearly 200 feet in air. To east and west the waters rose, a long blinding sheet of white. Far and wide the great wall spread, defying the human eye to take in its breadth and height and thickness. The contortion of the wreathed waters was like the dumb agony of some stricken thing. . . .

All around the place the water was turned to a dirty brown by the upheaval of the bottom of the river. The foam was still bubbling, nearly 10 minutes after the explosion. Thousands of pieces of wood, mingled with marine weeds and myriads of dead fish, killed by the shock, were floating down into the East River. . . .

Industrious and thrifty fishermen, armed with scoop-nets, ladled dead fish out of the water into their boats and prepared to make to themselves a feast.

Shattered remains of Flood Rock were collected and used to fill in the gap between the Mill Rocks, creating the single island that exists today. Mill Rock was acquired by the Parks Department in 1953; it's seen occasional recreational use since then — perhaps most notably as co-host of the 1969 New York Avant Garde Festival — but is currently off limits to the public.

That's the Harlem River Drive on the lower level; the cars on the ramps above are heading into the Bronx via the Willis Avenue Bridge.

I thought this would just be a lighthearted picture, but upon googling the name of the church things turned dark fast. I don't know if Pastor Streitferdt ever ended up serving any time in prison, but it looks like he's still in charge of the church today.