This building opened in 1913 as the Mount Morris Theatre. The following year, four local burglars were arrested after cleaning out a nearby tailor shop and stashing the stolen goods in the theater. A cop spotted the theft in progress and followed the men back here, imitating a stumbling drunkard so as not to arouse their suspicion. After other officers arrived on the scene, the police raided the building. The thieves attempted to escape, but the cops pursued them through the theater, "even into the fly loft, jumping and swinging through space like a bunch of bats."

A few years later, according to a piece in Cigar Aficionado written by Groucho Marx's son, a preteen Milton Berle got an early career break here when he was hired to appear with Irving Berlin one evening, singing Mr. Berlin's "Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning" from a box beside the stage, skirting a child labor law that prohibited children from performing on stage at night.

As World War I was raging, the newly formed Institutional Synagogue began meeting here. In a speech at the synagogue in 1918, not long before the passage of the Sedition Act, Congressman Julius Kahn said he had been informed that many neighborhood residents were opposed to the war. He then "told [the] large audience . . . that immediate and direct measures must be taken by the Government to silence all individuals and organizations that raise their voices against the war", exclaiming to the cheering crowd:

"When a seditious or traitorous voice is raised here . . . I hope the hand of the law will reach out and grasp the speaker. I hope that we shall have a few prompt hangings, and the sooner the better. We have got to make an example of a few of these people, and we have got to do it quickly."At the end of 1919, the theater reopened as a burlesque house. By 1932, "it was featuring Latino stage and musical performances", and continued operating as a series of Spanish-language theaters, most notably El Teatro Hispano, until at least the mid-1950s. You can see a 1934 drawing of the building here.

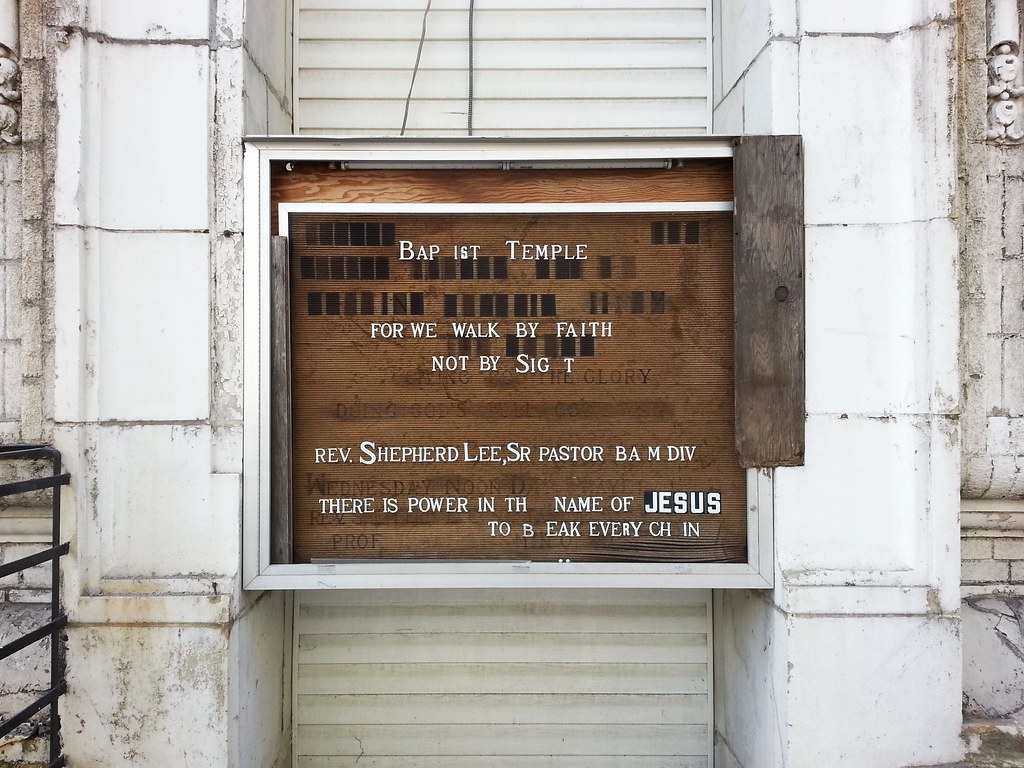

Built in 1906, today's Baptist Temple was originally home to Congregation Ohab Zedek (photo), which in 1912 "thrilled worshipers" by hiring the renowned European cantor Yossele Rosenblatt. (Last year we passed by Congregation Anshe Sfard, where Mr. Rosenblatt was later employed.) The following "classic Rosenblatt shtick" shows the great regard in which the famed tenor (a few of whose recordings you can listen to here) was held:

A young cantor billed himself as "The Third Yossele Rosenblatt."In 2009, concerns about the building's structural stability led to part of its facade and roof being torn down. Google Maps has a cool new feature that allows you to see all the Street View images taken at a certain place over time; you can use it here to see what the Baptist Temple looked like before its partial demolition and during its subsequent reconstruction.

"And who," he was asked, "was the Second Yossele Rosenblatt?"

"Feh!" he replied in disgust, "Everyone knows there could be no Second Yossele Rosenblatt!"

The Kalahari condominium, with a facade "inspired by South African Ndebele tribal designs"

Andrew Haswell Green was "arguably the most important leader in Gotham's long history, more important than Peter Stuyvesant, Alexander Hamilton, Frederick Law Olmsted, Robert Moses and Fiorello La Guardia", accordingly to the historian Kenneth Jackson. He was the driving force behind the creation of the modern five-borough New York City in 1898, and he was also a key figure in the establishment of several of New York's most notable institutions: Central Park, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, the New York Public Library, and the Bronx Zoo, not to mention the Washington Bridge and Riverside, Morningside, and Fort Washington Parks. An NY Times piece published late in his life recounted these accomplishments, as well as others "in the same general line, pursued with the same longsightedness and the same steadfast fidelity to a high standard of public service and personal conduct, so that in his ripe age no member of this vast community more richly merits the honorable title of Citizen of New York."

He was a man of great integrity (that makes two now!), and while he may have been "an imperious skinflint", "overbearing and stingy", and certainly "not the kind of guy you'd party with", his sober frugality was a much-needed virtue in the halls of government. Appointed city controller in the aftermath of the Tweed Ring scandals, he helped rescue New York from financial ruin at a time when "the city and county finances [were] in confusion . . . the Treasury empty, the city's credit seriously impaired, taxes excessive, the debt swollen beyond all precedent, city laborers and employes clamoring for pay, public institutions without funds to feed the hungry mouths of their wards, and the public buildings, markets, streets, and docks dilapidated and despoiled." Reflecting the regard in which he was held, the New-York Tribune wrote of his appointment at that dark hour: "The man who now holds the keys of the City Treasury is incorruptible, inaccessible to partisan or personal considerations, immovable by threats or bribes, and honest by the very constitution of his whole nature."

But despite the deep impact he had on the city's development, Mr. Green is largely unknown today. More than a century after he was murdered in 1903 in a bizarre case of mistaken identity, this hilltop bench in Central Park was the lone public monument to his life and work. (An "award-winning statue" of the man was created for the city's Golden Jubilee in 1948, but was never put on permanent display and ended up relegated to a garage in Maine.) And if that weren't enough of a slight on its own: the inscription on the bench states that "this eminence was named Andrew H. Green Hill", but the bench was booted off said eminence and relocated here in the 1970s or '80s to make way for a composting operation. Thanks to the tireless efforts of Manhattan borough historian Michael Miscione, however, the city has finally decided to honor "the Father of Greater New York" with something a bit more prominent: a waterfront park on Manhattan's East Side in the shadow of the Queensboro Bridge. (Now we just have to hope it doesn't fall into the East River.)

An even better honor would have been one Mr. Miscione was specifically pushing for: renaming the Washington Bridge after the master planner who first proposed building it. Rechristening the beautiful but often overlooked Harlem River span would not only be a more fitting and more conspicuous way to remember this forgotten civic hero, it would also help clear up a particularly confusing aspect of Upper Manhattan's transportation infrastructure: there are three vehicular bridges in close proximity to each other around 180th Street, and two of them are named after George Washington! Even Google can't keep things straight, labeling the lanes of the Washington Bridge with the name of its much more famous Hudson River counterpart, the George Washington Bridge.

So let's hear it for the Andrew H. Green Memorial Bridge — bringing recognition to a great public servant and clarity to our city's bridge nomenclature all in one fell swoop!

It was . . . in June 2005, that residents of the Upper West Side got their first glimpse of the two glass-sheathed towers that were to rise on Broadway at 99th Street. The local community board was having its monthly land use meeting — not generally an occasion of high drama — and Gary Barnett, president of the Extell Development Company, came to share renderings of his proposed buildings. As he unveiled them, a gasp was heard throughout the room. "People shrieked," recalls Sheldon Fine, chairman of Community Board 7.Dwarfing their surroundings, these two soaring apartment towers, Ariel East (pictured) and Ariel West, were controversial additions to the skyline of the Upper West Side. The community board was so upset by the enormity of the structures that it pushed through a rezoning plan to limit the height of future buildings in the area. (Somewhat ironically, of course, these height restrictions also effectively protect the commanding views currently enjoyed by those residing on the upper floors of the Ariels.)

What caught my eye, however, was not the height of the pictured building, but the glaring sheet of reflected sunlight it was casting on, and through the windows of, the building to its south (closer look) — which certainly can't be helping it endear itself to the neighbors.

Constructed in 1898, this building was originally the Bloomingdale Branch of the New York Free Circulating Library. It became part of the New York Public Library when the two systems merged in 1901, and it continued serving as a branch library until 1960. Since 1961, it's been home to the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., with part of the space fittingly used to house the academy's research library.

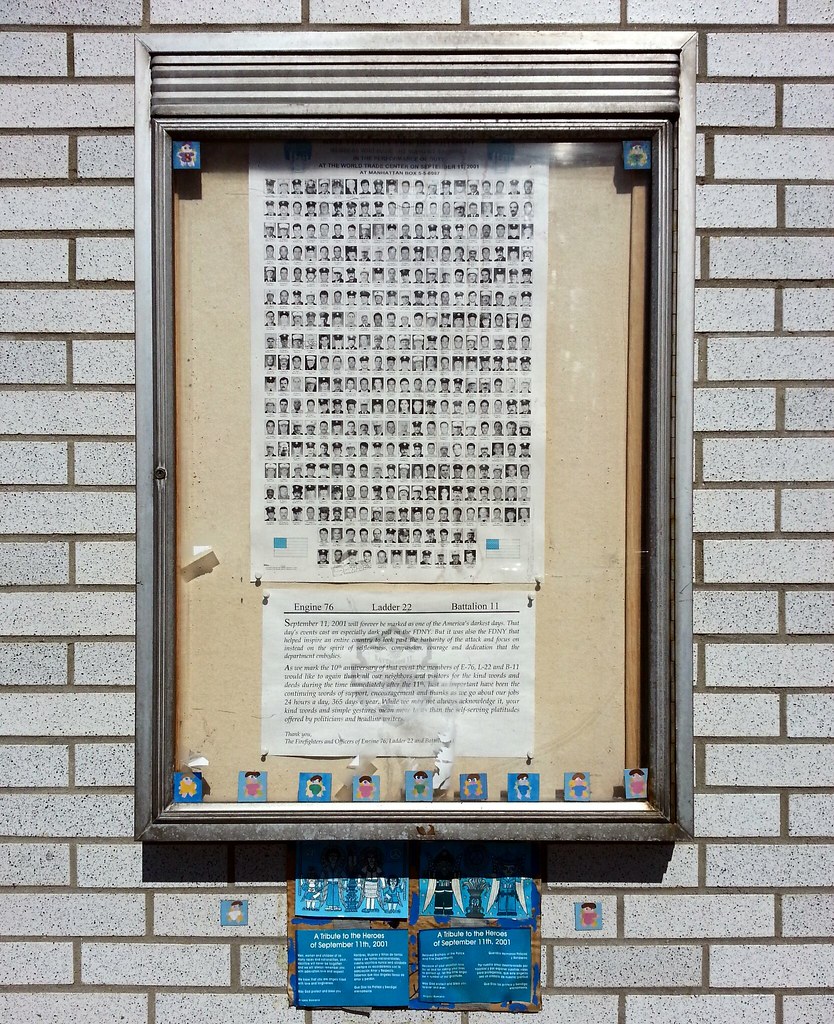

Dedicated to the fallen "soldiers in a war that never ends", this 1913 monument on Riverside Drive has long been the site of an annual ceremony commemorating city firefighters who lost their lives during the previous year. There is also now a memorial service held here every September 11th to pay tribute to the 343 members of the FDNY who were killed on 9/11.

The diamond-shaped plaque embedded in the bricks in front of the memorial, dated 1927 and "subscribed under the auspices of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals", reads:

THIS TABLET IS DEDICATED

TO THE HORSES THAT SHARED

IN VALOR AND DEVOTION

AND WITH MIGHTY SPEED

BORE ON THE RESCUE

Happy Warrior Playground, named for Al Smith, a four-term governor of New York and the 1928 Democratic presidential candidate

a.k.a. Goat Park or The Goat, home of the Goat Courts

a.k.a. Rock Steady Park, former hangout of the Manhattan chapter of the Rock Steady Crew (video)

Completed in 1914, 780 West End Avenue was designed "in a radically different style from other apartment houses of the period" by the brothers George and Edward Blum, who "formed one of the city's great nonconformist architectural firms". You can see more photos of the building here.

Here we have another magnificent bank turned CVS, this time with a private preschool located in the building as well.

On April 4, 1932, two days after the ransom for the Lindbergh baby kidnapping was paid, a teller at this Upper West Side bank branch made the first discovery of a ransom bill that had been spent. Hundreds of the bills would later be identified in bank deposits, but it took almost two and a half years before the case was finally cracked open, when a ransom bill was found — at a now-abandoned bank in Harlem we saw last summer — with the license plate number of the man who passed it scribbled in the margin by a gas station attendant who thought it might be counterfeit. This information led the authorities directly to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, who was later convicted and executed for the kidnapping and subsequent murder of the Lindberghs' son.

St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral, headquarters of the US/Mexican branch of the Russian Orthodox Church. Interior photos here.

Opened in 1991, this was the first structure in the city built as a mosque. The "spare, serene and deliberately modernist work" (see more photos) was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (architects of the Sears Tower, the new One World Trade Center, and Dubai's Burj Khalifa, which at over half a mile in height is by far the tallest building in the world) and was mostly financed by Kuwait, although many other Islamic countries provided support as well. In order to face the Kaaba, the mosque is oriented along the great circle route from Manhattan to Mecca (i.e., the shortest path on the surface of the globe between the two points), hence its 29-degree rotation off the street grid.

Mr. Codman, an architect and decorator who wrote The Decoration of Houses with Edith Wharton, designed this century-old French-style town house as a residence for himself. The Manhattan Country School has occupied the building since 1966, but is currently planning to sell it and move to a larger space.

This Madison Avenue facade is all that's left of the old armory, which was leveled in the 1960s to make way for a new school building (just visible at the far left) now occupied by Hunter College Elementary School and Hunter College High School. The original plan was to knock down the entire armory, but the city decided to protect the facade by designating it a landmark "just as the wreckers were about to demolish it." It now stands as "a dramatic backdrop for the school's playground" (photo).

This "sumptuous, Regency-style limestone house" was built in the early 1930s, its 55 rooms occupied by Mr. Loew, his wife, and 16 servants. Along with another massive residence erected on this block of East 93rd Street in the early years of the Great Depression, it was one of the last grand mansions constructed in Manhattan. In more recent years, it was home to the Smithers Alcoholism Treatment and Training Center before being purchased in 1999 by the private all-girls Spence School.

Sculpted cattle skulls are an unexpected sight on the frieze of this brick mansion, an "elegant amalgam of Federal and Georgian styling" (photo) constructed around 1917. The house, along with a ballroom addition to the west (photo) built around 1928, was purchased by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR) in 1958 and continues to serve as the church's headquarters. ROCOR split off from the Russian Orthodox Church (whose US/Mexican headquarters we just saw a few blocks away) after the Russian Revolution, "when overseas exiles refused to accept the domestic church's subservience to the Soviet state", but the two churches re-established canonical communion in 2007.

from a glassy Harlem condo onto the frozen waters of the Harlem Meer

This minimum-security prison across 110th Street from Central Park has in recent years been home to Malcolm X assassin Thomas Hagan and disgraced former Tyco CEO Dennis Kozlowski (he of the $6,000 shower curtain and the vodka-urinating ice sculpture of Michelangelo's David).

Constructed in 1914, today's prison was originally the headquarters of the Young Women's Hebrew Association, serving as a dormitory and education center. (The roof, now caged, featured a garden in those days.) Presaging its current role as a place of involuntary confinement, the building saw later use as Army housing and as a school. In both cases, like today, it was surely filled with inmates dreaming of their eventual freedom.