The cable you see at my feet helps support a wire mesh netting that covers the cliff face to prevent loose rocks from crashing onto the FDR Drive below.

That's the Washington Bridge, mind you; not to be confused with the nearby George Washington Bridge.

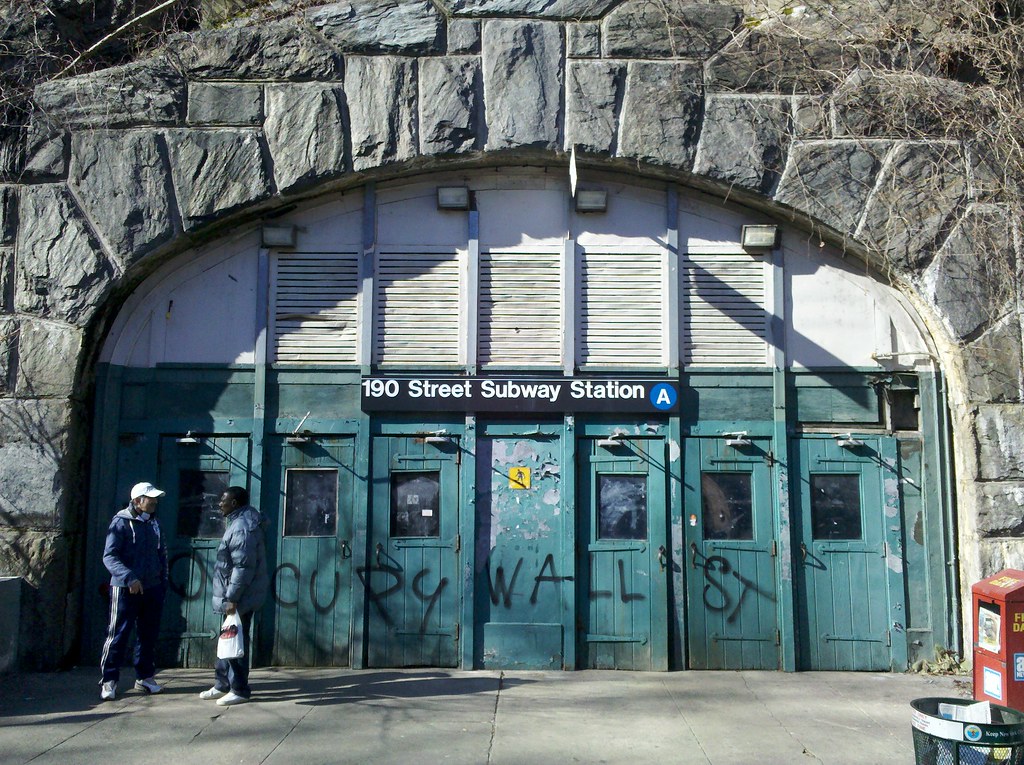

This is the 190th Street A station, where Victor Hess performed his subterranean radiation research.

You can see three of our old acquaintances in this photo. Two are pretty easy to spot; the third (which we haven't actually seen before — we've just seen the same type of thing) is not. Need a hint for Thing No. 3?

Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter II, better known as Reverend Ike, was a charismatic, flamboyant preacher who, during his 1970s heyday, spread his prosperity-based doctrine of the Science of Living to a TV and radio audience of some 2.5 million people, becoming a multimillionaire in the process. In 1969, he purchased the former Loew's 175th Street Theatre, a "delirious masterpiece" built in the "Byzantine-Romanesque-Indo-Hindu-Sino-Moorish-Persian-Eclectic-Rococo-Deco style", and turned it into his headquarters, renaming it the Palace Cathedral. (It's also known as the United Palace Theatre in its more recent role as a part-time music venue.) Rev. Ike passed away in 2009, and his son has since taken the reins of the church. Hopefully I'll find myself back here on a Sunday and will be able to take a peek inside.

This World War I memorial stands in Mitchel Square, across from NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center. There are no typos in the previous sentence.

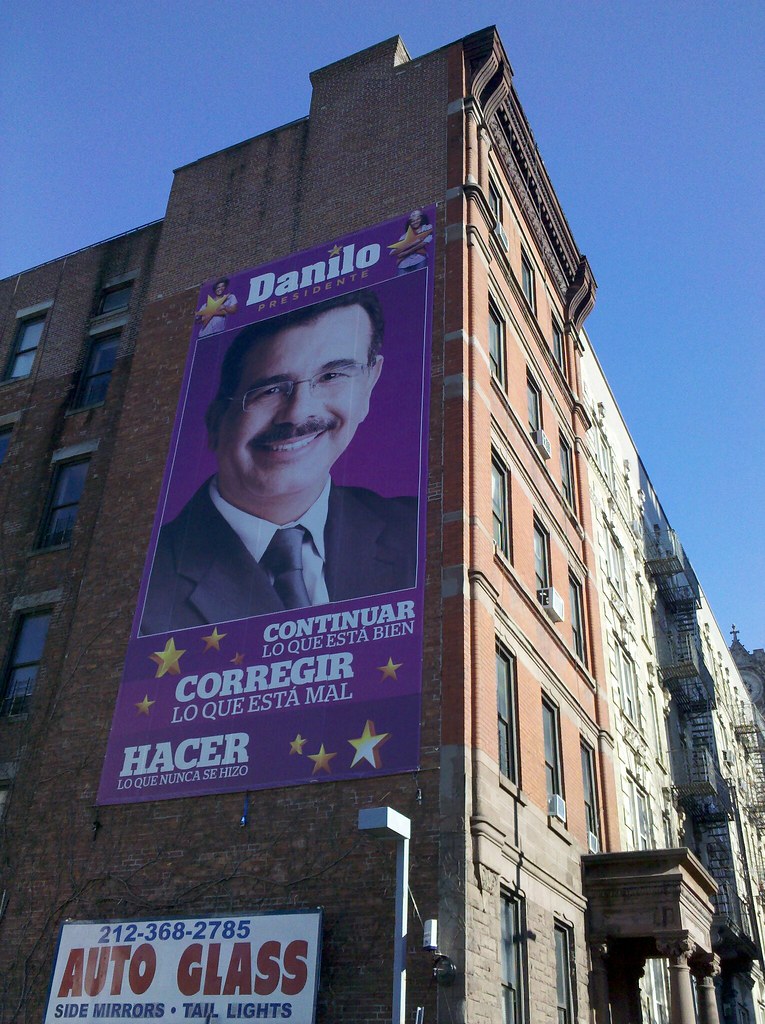

He's running for president of the Dominican Republic. I learned this when I saw his face a hundred times today in Washington Heights and Inwood. There are almost 600,000 Dominicans living in NYC (making them the most populous foreign nationality in the city), and since 2004 they've been able to cast votes for their national elections from polling centers here in New York.

The estate of the famed naturalist and painter lay just across 155th Street from Trinity Church Cemetery, where this monument stands.

Completed in 1848, it's the oldest bridge still standing in NYC (sort of — in order to improve navigation on the Harlem River, five of the original masonry arches were replaced by a single steel arch in 1927). A beautiful, stately structure in its own right, it was but one component of a truly extraordinary engineering project.

There are several plaques like this around Swindler Cove Park providing information on the construction of homes for different types of wild animals, from bats to owls to squirrels.

Technical note: There are tons of streets in New York that have been renamed for heroes and victims of 9/11. For the purposes of enumerating 9/11 memorials, and because they have so much in common with one another, I'm going to count all the renamed streets as individual components of one large citywide memorial. Memorial #11 was the first renamed street I noticed, so I'll consider all other renamed streets to be part of #11 as well.

This city seal predates 1915, when a uniform standard was created. It's quite unusual to see the fire department referred to as NYFD instead of FDNY; perhaps that was a more common abbreviation in the days of yore.

The Dyckman family had acquired around 250 acres of farmland here in northern Manhattan by the time of the Revolutionary War. They fled Manhattan when the British forces captured and occupied it in late 1776, and they didn't return until it was back in American hands after the end of the war in 1783. The British had destroyed their home during the war, so the Dyckmans built this farmhouse to take its place.

About a quarter of the British fighting forces in the Revolution were actually German soldiers hired out, often against their will, by their princes. Almost half of these 30,000 troops hailed from the principality of Hesse-Kassel, and so the lot of them became known as Hessians. In 1914, a local amateur archaeologist by the name of Reginald Pelham Bolton discovered a Hessian encampment that had been built on the Dyckman farm during the war. He reconstructed this hut, which would have housed six to eight Hessians, on the grounds of the Dyckman Farmhouse, which was just being restored at that time.

While wandering through Inwood Hill Park today, I came upon a group of people gazing up at a tree. It turns out they were looking at a Great Horned Owl, hidden amongst the leaves of the dead branch hanging down from the tree in the center of the photo. After a sufficient amount of intent staring, I was finally able to see it. (It's in this photo, but it's completely indistinguishable.)

I hung around for a little after everyone else took off, and then started on my way again. A couple of minutes later, I ran into two older Korean men who had heard about the owl and were wondering exactly where it was, so I took them over to the tree and pointed it out to them. One of the men was wearing a fedora and a bright turquoise scarf, which reminded me of something I had seen before...

On a previous walk through Inwood Hill Park, I found some mysterious circles carved into the soil. They contained patterns of different shapes and textures and colors, and were made entirely with materials from the surrounding forest. They were very thoughtfully constructed, and had clearly required a lot of time and effort. A guy (who happened to be Phil Roy) came by walking his dog, and I asked him if he knew what these circles were. He told me all about an older Korean guy, named Young, who comes out to the park every day and works on them. When I got home I searched the internet for information about Young, and stumbled upon an incredible video of him calling a woodpecker and then feeding it in his hand. I was completely transfixed, not just by the beautiful bird, but by something in Young's demeanor, and I watched the video several times.

Ten months later, when I ran into two older Korean gentlemen on a trail in Inwood Hill Park, and I saw a familiar-looking face and hat and scarf, something clicked...

Young gave me a tour of his creations, which number about three times what you see in this picture and the previous one. This piece represents the endless cycle of water flowing to the sea, evaporating, and returning to the earth as rain.

Young retired in 2007, and ever since then he's been coming to the park every day — rain or shine, summer or winter — to work on his "garden" (my term, not his) and spend time walking in the woods. He says he can feel a tremendous power coming from the earth when he is forming these shapes and patterns. To my eye, they are beautiful works of art, but I think to Young they are much more spiritual in nature.

Inwood Hill Park contains the last real forest in Manhattan. The towering trees, rock outcroppings, and isolating topography make it the only place on the island where you can really get a sense of what things were like before the arrival of the Europeans. It's an extraordinary enclave of rooted history in a city that's constantly in flux. Could Young's work exist anywhere else?

The vulnerability of these pieces to the weather and other natural processes is integral to their power, and it also means Young has an ever-changing canvas on which to work. If you're ever in the area, just head down into the valley between the two ridges in the park. Keep walking along the main north-south trail, and you'll find the garden soon enough.

Inwood Hill Park contains some of the last remnants of the salt marshes that once surrounded Manhattan.

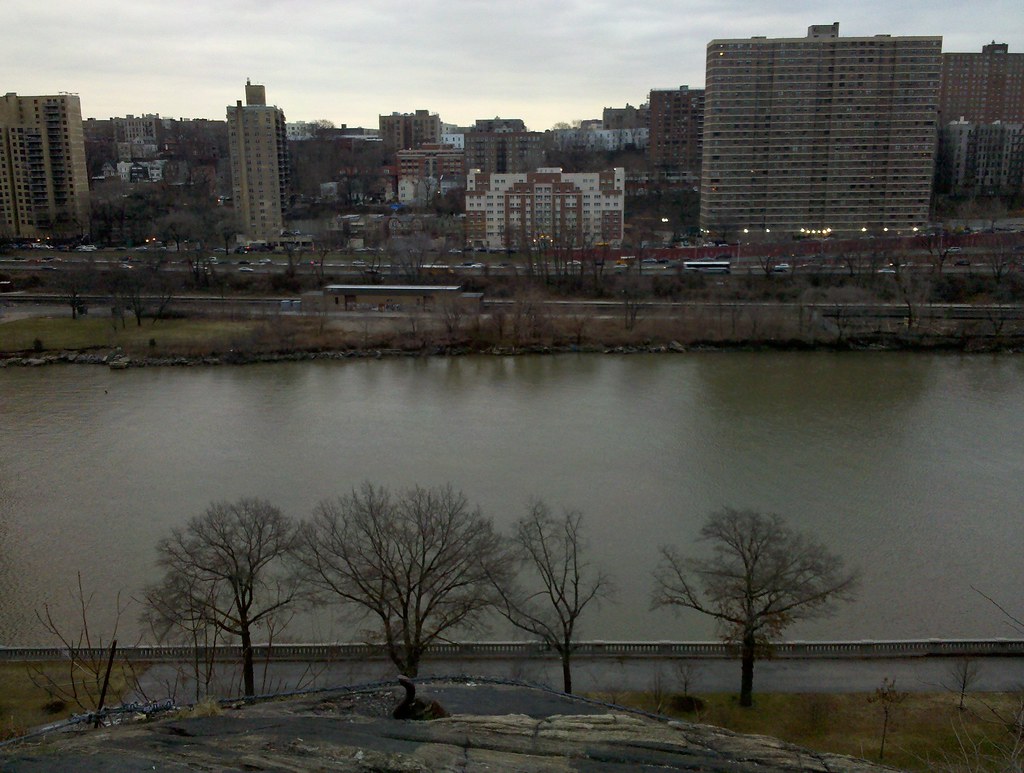

To the right you can see the Inwood Hill Nature Center, originally built as a boathouse.

Replica of a Lenape wigwam at the Inwood Hill Nature Center

This bridge, completed in 1936 (here's a great shot of it under construction), always takes my breath away, although it's a shame that the Henry Hudson Parkway, which passes over the bridge, runs along the western edge of Inwood Hill Park through the only substantial forest left in Manhattan. Robert Caro, in his biography of Robert Moses, talks about the decision-making process behind the location of the roadway. The original proposed alignment of the parkway was east of Inwood Hill Park, and this design was favored by many urban planners, but Moses decided to build it through the park instead, because that would enable him to take advantage of free labor from the Civil Works Administration under the premise that he was building a "park access road", and it would also save the city the expense of condemning buildings needed for the parkway's right-of-way.

Originally painted by Columbia University's crew team sometime in the 50s, the C has a bit of mystery surrounding it.

Inwood marble is much softer than the other types of Manhattan bedrock, and so it erodes much more easily. There were once veins of marble surrounding Manhattan, connecting it to the adjacent landmasses. As the marble washed away, it created the channels that eventually eroded into the waterways now encircling Manhattan: the Hudson, East, and Harlem Rivers.

This is, by some apocryphal accounts, the spot where Peter Minuit purchased Manhattan from the Lenape tribe. The popular imagination has him swindling these poor Indians out of their ancestral homeland for a mere handful of trinkets and beads (perhaps that's what the apple and coins tucked up against the rock symbolize?), but of course the story is not actually that simple.

This rail bridge currently carries Amtrak trains on the Empire Corridor.

I was taking a picture of another "adequate wiring" sign when Eddie, the super, stepped outside. I asked him if he knew how old the sign was. He did know, and he told me. And then he told me 20 million other things. Including:

He was born in Puerto Rico, but moved here to Webster Avenue when he was just a few years old. He and his family were the first Puerto Ricans to move into the neighborhood, and he's witnessed all the changes that have happened since then. He pointed out where the candy store used to be, and the Italian bakery (he loves Italian bagels), and the synagogue. He talked about the trolley line that used to run down Webster Avenue, and he told me about the 1970s, when a cop was shot in the playground down the block, and when he himself was shot and stabbed. He's taken and collected decades of photos of the neighborhood, which I'd love to see sometime. People have asked him if they could buy the old sign I was photographing, but he wants it to stay up on the wall, just as a little trace of the past. (I've forgotten how old he said it was.)

When I asked if I could take his picture, he said I would have to wait until he mopped the foyer, because he didn't want there to be a dirty floor in the picture. He also has a really nice smile, but insisted on keeping a straight face in the photo because he doesn't want anyone seeing his missing teeth.