This cultural center has been located here on Jamaica Avenue since 1979.

These colorful flags are a common sight in Indo-Caribbean neighborhoods.

Built around 1900 "in a de-shingled Shingle Style", this was originally the First German Presbyterian Church of Jamaica, and the partially boarded-up house at left (old photo, Street View) was the manse.

One Sunday evening in 1910, the Rev. Ferdinand O. Zesch, pastor of the church, was preaching to his congregation from the pulpit. According to the NY Times:

As he continued talking he became more and more spirited in his delivery. Suddenly, in the middle of a highly charged sentence, his uplifted right hand fell upon the Bible, his face became convulsed with pain, his voice stopped, and he caught hold of the pulpit stand to steady himself.

After wavering a moment back and forth he staggered over to a seat at the back of the stand and sat down. Many of the women in the congregation began to cry. Several men ran to the stricken preacher. He indicated by gestures that something had gone wrong with his heart. He was lifted over to a cushioned pew, where he lay down.

Dr. Phillip Wood . . . was sent for, but Mr. Zesch died before he arrived. The doctor said that death had been caused by the bursting of a blood vessel in the region of the heart, due to excitement and a diseased condition of the heart. Mr. Zesch was 60 [or perhaps 58] years old.

According to the Parks Department: "This playground takes its name from Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States."

Why would a playground in Queens be named for Harvard University? I suspect it was not actually named for the university, but rather for Harvard Avenue, the former name of the street on which the playground is located. (It was changed to 179th Place in 1919.)

Located in the well-to-do neighborhood of Jamaica Estates, this old Jamaica Water Supply Company pumping station was apparently intended to look more architecturally refined than its brethren in other parts of southeastern Queens.

Gamewell (awesome logo) was the dominant manufacturer of fire call boxes in the US, but it's quite rare to spot one of the company's boxes here in NYC. Within the city, they're apparently found in just a few Queens neighborhoods. This one in Jamaica Estates is only the second that I've noticed, and the first intact one: the other was retrofitted with a modern fire/police button unit.

The cylindrical thing on top is a mechanical Arrestolarm, which would have blasted a "loud and distinctive warning shriek" whenever the box was triggered. This was intended to discourage pranksters from setting off false alarms by drawing immediate attention to anyone reporting a fire, like the hastily robed young woman below.

This one is also located in Jamaica Estates, just a couple of blocks away from the previous one.

Fresh Anointing International Church, the former Conservative Synagogue of Jamaica Estates

The dense vegetation conceals the fact that this is a very narrow sliver of woodland, with Kissena Golf Course to the left and a Department of Environmental Protection storage yard to the right. Here's an aerial view.

The thing beneath the street sign was once a light-up police call box sign.

This little triangle of parkland takes its name from Samuel Butler's 1872 novel Erewhon: or, Over the Range. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Butler's imaginary land of Erewhon

at first seems utopian in its disregard for money—which lends status but has no purchasing value—and machines—which have been outlawed as dangerous competitors in the struggle for existence. Erewhon has also declared disease a crime for which the sick are imprisoned, and crime is considered a disease for which criminals are sent to the hospital. As the unnamed narrator further examines the institutions of Erewhon, his illusions of utopia and eternal progress are stripped away.You may be wondering what connection this sparsely planted wedge of concrete could possibly have to Erewhon. I've learned that a good first step in trying to decipher a park name is to look at a map, because former Parks Commissioner Henry Stern often used the names of adjacent streets as inspiration for park names. And that appears to be exactly what he did here, as the street on the west side of Erewhon Mall is Utopia Parkway. In an article titled "Erewhon and the End of Utopian Humanism" in the journal ELH, Sue Zemka says that Erewhon was

written with Sir Thomas More's Utopia in mind. More combined two words to coin his seminal neologism: "eutopos," which means the good place, and "outopos," the place which is nowhere. "Erewhon" is "nowhere" misspelled backwards, the soft vowel beginning of "eutopia" thus recalled in a word which, like "utopia," also inscribes its negation.

Built in 1906-07, the former Firemen's Hall now serves as the headquarters of the College Point Little League and is also home to a senior center.

Built in 1857, this old mansion is the last substantial house from the mid-19th century still standing in College Point. It was turned into a hotel in 1892 and was divided into apartments in 1923. I'm not sure what kind of shape the place is in today, but some of the tenants said the interior was in disrepair after they were forced to vacate in 2008 because of the house's dangerously antiquated electrical wiring. The residents were allowed to return eight months later, but were still without gas for several more months while repairs continued.

Today the house is prominently and uniquely sited, standing alone on a circular traffic island. In its earlier years, it was part of a large walled estate. According to the city's Landmarks Preservation Commission:

The Schleicher House originally stood at the end of tree-lined, semi-circular drive. The rear elevation [above] faced east, toward a sloping, almost circular lawn, ringed by trees. South of the house stood a "back" house or privy, suggesting that at the time of construction the bathrooms were not served by running water. To the north of the house, from west to east, was planned a large vegetable garden with rows of fruit trees, a coach house and stable, a hen house, and duck yard. There were also asparagus beds and winding carriage paths that led to an oval pond at the northeast corner of the estate, near present-day 125th or 126th Street. At the center of the pond was a small island, reached by a bridge. Here stood a small "summer" pavilion and "back" house.

Chief Stack was one of the 343 members of the FDNY killed in the September 11th attack on the World Trade Center. While a memorial service was held for him in 2001, his family put off his funeral in the hope that some of his remains would be found and identified. But they finally decided they had waited long enough, and on June 17, 2016, the 49th anniversary of Chief Stack's marriage to his wife, Theresa, the family and the fire department held a funeral service and buried a vial of blood he had given in 2000 when he signed up as a potential bone marrow donor (not the only time a sample of blood has had to stand in for the remains of a 9/11 firefighter). As far as I can tell, it was the first funeral for a firefighter killed on 9/11 in over a decade, since Gerard Baptiste's in 2005.

(In case you're wondering, I don't count individual streets renamed for 9/11 victims as memorials in my running tally; I consider them all to be part of one citywide memorial.)

The geometry of the Whitestone Bridge is echoed by this fence running along the perimeter of the public waterfront area at Powell Cove Estates in College Point.

East of MacNeil Park in College Point, there are three neighboring residential developments built out onto a peninsula that juts into the East River. Clambering around the peninsula at water level, you encounter lots of old construction debris, like this tangle of rebar and concrete.

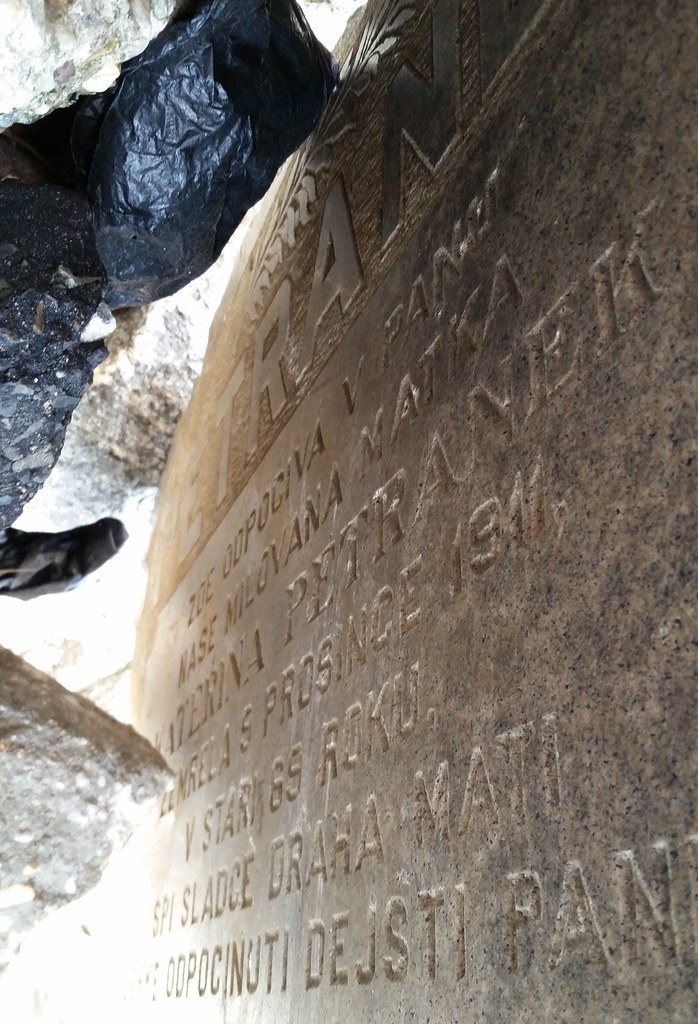

Continuing around the base of the peninsula, I found this carved piece of stone mixed in with all the chunks of concrete. At first I thought it might have been part of the facade of an old synagogue, but then I looked a little closer...

I was standing here thinking about what I had seen so far when I realized I was looking right at a big headstone flipped upside down. Peering beneath it, I was able to make out a name: Katerina Petranek.

The inscription is in Czech:

ZOE ODPOCIVA V PANU

NASE MILOVANA MATKA

KATERINA PETRANEK

ZEMRELA S PROSINCE 1911,

V STARI 69 ROKU.

SPI SLADCE DRAHA MATI

LEHKE ODPOCINUTI DEJSTI PANE.

A rough internet translation tells me that Ms. Petranek died in December 1911 at the age of 69.

So what in the world are all these gravestones doing out here? It turns out that this peninsula I've been scrambling around, with the residential developments built on top of it, is a former landfill that was in operation from about 1963 to 1977. (Compare aerial images from 1951 and 2012 to see the extent of the landfill.) All sorts of things were dumped here over the years, including lots of stones from cemeteries.

Because we treat death and the burial process with such sanctity, it's quite shocking to find these stones haphazardly strewn about the waterfront, and one's immediate sense is that there must be something scandalous going on. But, of course, sometimes gravestones do need to be replaced, and the old ones have to be discarded somewhere. It's just that, in this case, they ended up on the periphery of a landfill that wasn't fully capped, and hence are still exposed and visible decades later. (I should note, however, that they're not exactly in public view. They can only be reached by those who decide for some reason to climb around a steep, rocky stretch of shoreline.)

Of the stones I've seen so far, Mr. Fisher's is the first that definitively matches up with a record on findagrave.com. He's interred in the old Hungarian Union Field Cemetery (now part of Mount Carmel Cemetery), one of the burial grounds that makes up the massive necropolis stretching across the middle of the Brooklyn-Queens border. I visited him there and found a different stone (below) marking his grave, smaller and simpler than the one above and identical in style to those of the other family members buried in his plot.

I was also able to find out where Mr. Kartman is buried. Weirdly, he's only about 25 feet away from my great-grandmother at Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens. I went to check on his new gravestone, but it had been knocked over, along with the two stones immediately adjacent to his (one on either side). I'm not sure what to make of this. Did a huge tree branch fall on them? Does someone have a grudge against him and his family? Before you jump to the latter conclusion, I should note that one of the fallen stones next to his (at left, below) is actually in a different section of the cemetery, meaning it presumably belongs to someone unrelated.

Mr. Warren, like David Kartman, is buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery. I visited his grave there and found the headstone pictured below.

Mr. Warren's widow, Frieda, died 38 years after him. My first thought upon seeing the new stone was that when she passed away, the couple's children, perhaps acting on the wishes of their mother, must have replaced their father's headstone with a shared one for both of their parents.

But Ms. Warren died in 1980, and an NY Times article about all the gravestones out here on the waterfront says the landfill in which they were dumped closed in 1977. Given that discrepancy, and because Mr. Warren's stone lies a few hundred yards east of where the vast majority of the others are clustered, I began to wonder if his stone, as well as some of the rubble surrounding it, was just illegally dumped on the beach here one night by a shady disposal company a few years after the landfill had closed.

Of course, it's also entirely possible that Ms. Warren had the new, shared headstone put in while she was still alive, and that Mr. Warren's old stone had to be removed and discarded while the landfill was still open.

This spot in Soundview Pointe (a.k.a. Soundview Estates), the westernmost of the three private residential developments built on top of the old landfill, offers the clearest look you can get at Tombstone Beach without climbing down to the water.

This stretch of pavement in Soundview Pointe/Estates, the westernmost of the three residential developments built on top of the old Tombstone Beach landfill, is pockmarked with an absurd number of manholes. I count 20 in this photo. Here's a closer look.

Among the abundant manholes of Soundview Pointe/Estates, there are quite a few covers that were made for the sanitary sewer system in Mahwah, New Jersey — at least eight, all dated 2007*. Were they purchased from Mahwah at a surplus auction? Was Mahwah unable to use them because of some defect? Did someone steal them? Given that the Soundview developers were the kind of people who see a contaminated landfill as a profitable place to build town houses, I wouldn't rule out any unconventional manhole-cover acquisition tactics on their part. I called the Mahwah Department of Public Works to see if anyone there could offer any insight, but the guy I spoke to found this all just as strange as I do.

* Soundview was under construction in 2007, as evidenced by these aerial images from 2006 and 2008.

This place is true to its name. I saw eight Corvettes in the shop.

Hey, looks like I've taken a photo here before!

New York Dong Won Presbyterian Church, formerly the synagogue of Congregation Agudas Achim