Linden Boulevard, which is interrupted several times in its journey across Brooklyn and Queens, comprises a handful of discontinuous roadway segments that vary from this mighty thoroughfare to the isolated little stub of pavement you see above.

This building was once a factory for the Knox Hat Company, one of the most well-known hatters of the early 20th century. Edward Knox, after recovering from serious injuries sustained during his service in the Civil War (for which he was awarded a Congressional Medal of Honor), returned to New York and took the reins of the family business. Over the years he expanded their operations from retail into manufacturing, and, in 1890, built this factory here in Brooklyn. It sat dormant for decades, suffering from decay and vandalism, before being renovated and turned into subsidized housing in the 1980s.

The life's work of Arthur and Cynthia Wood, Broken Angel was cited for numerous building code violations after a fire in 2006, and the Woods were forced to dismantle an incredible, multi-story rooftop structure they had built. For a look at many of the building's unique features, check out this photo gallery posted by the Woods' son, Chris. The NY Times also has a terrific shot of the whole complex.

Cynthia died in 2010 after a battle with liver cancer, and Arthur lives here alone now. Brandon Stanton spent some time with him last summer, and wrote about the experience for his Humans of New York project.

This line was abandoned in 1949, but there are still a couple of surviving sections of track. The elevated structure above is the Myrtle Avenue Line (M train), a remnant of the old Myrtle Avenue El.

CORRECTION: It's a subway vent! More info here.

When those late-night 25-o'clock hankerings hit, you know where to go.

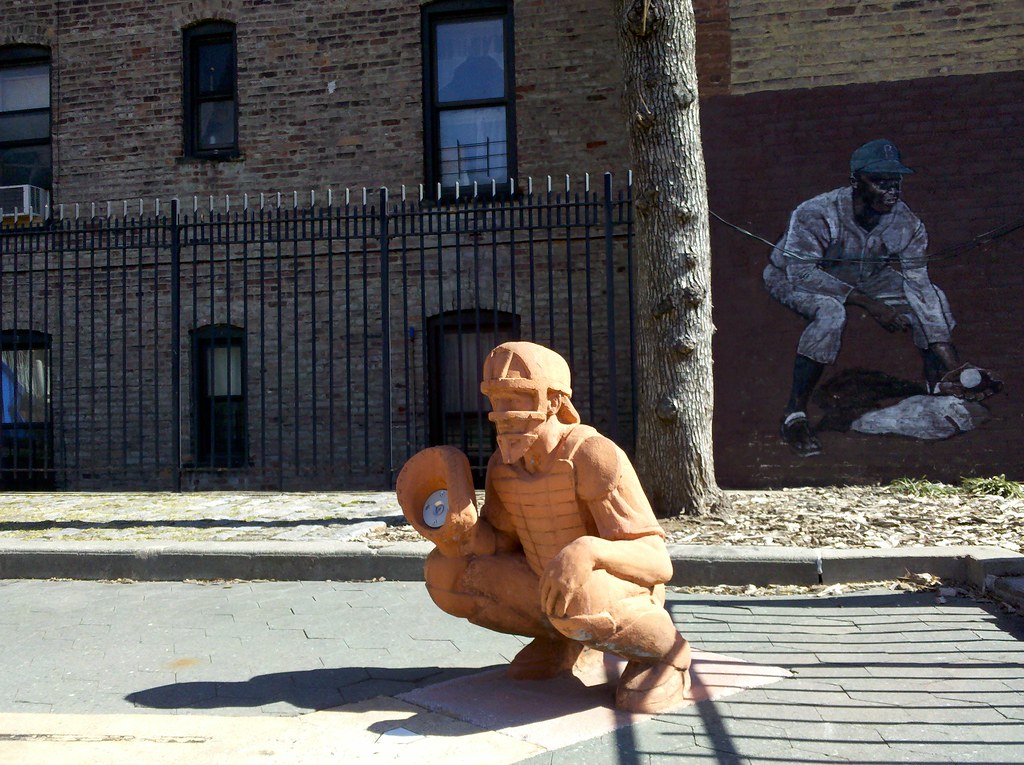

That's a Roy Campanella spray shower, with Jackie Robinson guarding second base behind him.

Tracy Jordan knows what it's like to live in a place like this.

Shomrim is a volunteer Jewish civilian patrol. Some of their vehicles bear a striking similarity to those of the NYPD, and at least one of them parks very close to other cars on occasion.

These three netball courts make up 60% of the city's total.

Once known as "Tickle Park", Lincoln Terrace served as a base for anti-aircraft guns during World War I.

Almost as loud as Ellwood and Jake's contraption, these speakers were blaring out something in Yiddish. I tried to ask the driver, who was not Jewish, about it, but we could barely hear each other over the noise. All I could understand is that someone is paying him to slowly drive around the neighborhood, blasting this message, whatever it is, to everyone within earshot.

Not the first armory we've seen on Bedford Avenue. This one was completed in 1907, with its massive drill shed soaring above the rest of the facility. It was home to a National Guard unit up until last summer, and has also served as a film set for several movies. The state is now looking to transfer ownership of the facility to the city, and a community meeting was recently held to talk about possible future uses for the structure.

There is a subtle feature of this mural that I missed when I first reported on it. I mentioned that the artist, Jason Das, avoided having to paint an infinite regress by cutting off the right side of his mural-within-a-mural. What I didn't notice was that he did this in an extremely clever way. As you can see here, his mural is slightly obscured by the panel to the right. If you look at the upper left side of that panel, you'll notice that Mr. Das actually extended his mural onto it, painting a smaller version of that panel on the panel itself. So the part of his mural that obstructs the edge of the mural-within-the-mural (preventing the infinite regress) is also the object that obstructs his mural in real life! Brilliant! (Although now we should see an infinite regress on that adjacent panel, I suppose...)

The original building that stood on this site was an African Free School, later renamed Colored School No. 2 after becoming part of Brooklyn's public school system. In 1893, it merged with the all-white PS 83 to form Brooklyn's first integrated school, with a racially mixed administration, faculty, and student body. The building you see here, constructed as a replacement for the original PS 83 building, was purchased from the city in 1978 by Bethel Tabernacle, one of the original churches of the Weeksville settlement. It was an expansive addition for the church, sure, but it had its drawbacks, too: the food was terrible and you needed a hall pass to use the bathroom. The church, whose main building is across the street, still owns this property, although they haven't used it in years.