Sometime in 2011 or 2012, the northbound lanes on this block of 4th Avenue just south of Flatbush Avenue were eliminated and an expanded sidewalk took their place. Embedded in the sidewalk is a large stylized image of a red rose.

In trying to determine if the rose has any particular significance to this location, all I could come up with is the fact that the Brooklyn Academy of Music's Rose Cinemas is located nearby, one long block away. (The Peter Jay Sharp Building, which houses the Rose, is visible in the background of this photo, behind and to the left of the school bus.)

But that connection seems like a stretch. Perhaps a rose was selected because it's the state flower of New York. The only thing standing on the small triangular block where the rose is located is an old subway entrance kiosk (the Times Plaza Control House), and the subway is run by the MTA, a state agency.

Or maybe they just put a rose here because people like roses.

I'm sure you're now dying to know about other relevant official flowers. How could you not be? The national flower of the US (or the "National Floral Emblem", technically) is... the rose! The official flower of NYC is the daffodil. All of the boroughs except Manhattan have their own official flowers as well:

The Bronx: day lily (previously the monstrous corpse flower)

Brooklyn: forsythia

Queens: tulip and rose (as seen on its flag), representing the Netherlands and England, respectively, the two nations that controlled what is now NYC during the colonial era

Staten Island: pinxter azalea

The most striking thing about this church, built 1929-1931, is not its unique, imposing architecture ("Gothic restyled in modern dress . . . that might be termed cubistic Art Moderne"), but rather something much more commonplace — three commercial storefronts! This church is not just a house of the Lord; it's also the home of a restaurant, a convenience store, and a deli.

(The only similar thing I can ever remember seeing is a church in Arlington, Virginia — another United Methodist church — that leases its ground floor to a gas station [Street View]. I've always thought that church's slogan should be "Fuel for your eternal combustion engine".)

My first thought was that these storefronts must have been carved out sometime in the past few decades. It's not uncommon to hear of a once-thriving church falling on hard times as its congregation dwindles. I figured this church must have been in a similar bind and decided to rent out parts of its building in order to make ends meet.

If you view old images of the church, you don't see any large commercial signs on the outside like you do today. This seemed to confirm the idea that the storefronts are a fairly recent creation.

But then I looked closely at this circa-1940 tax photo and started to wonder. It does kind of look like there may have been independent, standalone storefronts in the locations where they are today. There are also some not-very-church-looking diagonal stripes by the archway at the far left.

This 1930 photo, taken late in the construction process, shows a financial campaign headquarters (presumably a temporary operation established to raise money for the church's construction) located in the rightmost storefront, where the deli is today. This seems to hint at the idea that today's storefronts may have always been separate units of the building, whether or not they were initially intended to be used commercially.

I finally found some fairly conclusive evidence when I searched the Brooklyn Daily Eagle archives for the addresses of the storefronts (13, 15, and 17 Hanson Place). Between 1938 and 1954, there were a ton of ads for Goldware Exchange, a gold/diamond/jewelry/pawn-ticket buyer located at 15 Hanson Place. (This seems like a particularly weird business to have at a church.)

I also found a couple of mentions, in 1940 and 1941, of a place called the Hanson Tea Room, located at 13 Hanson Place. Then I found a 1933 ad for the tea room that doesn't list the address but says the place is "adjoining Williamsburgh Savings Bank". Because the church is the only building adjoining the iconic Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower on Hanson Place (they're the only two buildings on their side of the block, in fact), I have no doubt that the tea room existed in the church in 1933.

So at least two of the church's storefronts (and there may have only been two originally; 15 and 17 could have been split later on) were already being rented within seven years of the building's completion. This makes it seem likely that it was part of the church's plan all along to support itself financially by leasing building space to commercial tenants.

Changing subjects, I spotted a newspaper listing for a "womanless wedding" while researching this post. I had no idea what that meant, but it turns out that womanless weddings — comedic performances of weddings with men playing all the roles in the wedding party, "including bridesmaids, flower girls and the mother of the bride" — were quite popular in the first half of the 20th century. They were often staged as large community fundraising events. In fact, our favorite Methodist congregation on Hanson Place put on a womanless wedding in 1930 to raise money for the completion of their new church. (The famous attendees mentioned in the linked article were not actually there; they were characters portrayed in the wedding.)

I found a couple of articles in the NY Times about a womanless wedding being held "for the benefit of crippled children" in Nyack, New York, in 1925, in which the mayor was going to play the bride. The day before the performance, two local men, including the man who was playing the groom, convinced the mayor to get all dolled up as the bride so they could drive around the county advertising the event. Once they returned to Nyack, the men tricked the mayor into stepping out of the car for a minute and then sped off, stranding him in the middle of town in his makeup, wig, and gown. This caused quite a stir, and the police, not recognizing the mayor, arrested him on a charge of "impersonating a female".

The publicity resulting from the arrest drew such huge crowds to the wedding that a second performance had to be scheduled the next night to accommodate everyone. If I'm reading this article correctly, it sounds like the mayor decided he had done enough for the town by getting arrested and locked himself in his office rather than participate in the wedding, but the event was a smash hit nonetheless.

If you're looking to stage a womanless wedding yourself but don't know where to start, I've got good news for you. You can see a script for one, published in 1918, here. You may just want to tweak a few things before presenting it to the public.

I also ran across this 1941 article detailing "a new form of warfare" being developed in Britain. As you probably guessed, the article is referring to troops on roller skates, zipping around at 30 miles an hour, armed with "revolvers, knives, 'knuckle dusters,' and sub-machine guns", and wearing uniforms "reinforced with rubber pads, enabling them to make flying tackles."

The Brooklyn Academy of Music's Peter Jay Sharp Building

These ladies make a couple of brief appearances in this video about the artist, Alan Aine.

The faces have been refreshed since I walked by back in 2015. Check out the before and after images.

I'll let you guess which part of this building is the original carriage house and which is the 21st-century addition.

In booze news, the Budweiser Brewing Company signed a five-year lease on this property in 1896. Then, during a Prohibition-era raid here in 1931, the aptly named Morris Martini was arrested and the following was seized: "126 quarts of sauterne, 12 quarts of champagne, 24 quarts of Rhine wine, 45 quarts of vermouth, 60 quarts of sherry, 72 quarts of port, 24 quarts of benedictine, 36 quarts of Scotch whiskey and 540 quarts of gin."

(A reader turning to page 3 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on December 22, 1931, would have learned of not only the arrest of Morris Martini, but also the death of Harry Butt.)

The soaring red and white tower in the distance, which stands on top of Brooklyn Tech, was built in 1966 to transmit the city-owned WNYE radio and television stations. It replaced a radio-only tower that had stood on the site since the 1930s (visible in this circa-1940 tax photo of 31 St. Felix Street). I'm not sure how tall the older tower was, but the current one rises to a height of 597 feet above the ground. This made it, in combination with the building beneath it, the tallest structure in Brooklyn from the time of its construction until about three months after I took this photo, when it lost its crown to the first of a growing number of 600-foot-plus skyscrapers in the area.

The skyline of Downtown Brooklyn and vicinity is undergoing a rapid transformation.

It is the undisputed king of the Brooklyn skyline, the most populous borough's only widely recognized piece of architecture that is not a roller coaster. . . . [It] casts its shadow over the congested crossroads of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues, towering a good 400 feet over almost everything in the vicinity and visible from the Jersey Shore.Andy Newman of the NY Times wrote those words back in 2002, when the 512-foot Williamsburgh Savings Bank Tower was still the tallest building in Brooklyn. Things have changed dramatically since then.

The stylistically incongruous dome that sits atop the 1929 tower, intended as a visual reference to the bank's previous headquarters, was hated by the building's architects but insisted upon by the bank. Over the years, the dome has found its way into the hearts of Brooklyn residents proud that their borough is home to "New York's most exuberant phallic symbol", lovingly dubbed "the Willie".

From the same Times article quoted above:

For the 16,000-odd customers of the branch, the basilicalike banking hall remains a pretty awe-inspiring place to fill out a deposit slip. From a 63-foot-high vaulted gold-leaf ceiling mosaic of zodiac figures and other celestial ephemera to the intricate wrought-iron biblical-looking men and women that serve as the legs of an inch-thick green glass counter illuminated by lamps hanging from stylized metal camel faces, the place dazzles.But the building was more than just a bank. It also evolved into an unlikely hub of oral health; at the high point, there were "well more than 100 dentists" with offices inside these walls. By 2005, that number was down to 40, and most of those were forced out shortly thereafter, when a development team that included Magic Johnson converted the place into luxury condominiums.

Near the top of the tower, you can see "what was for decades the largest four-faced clock in the world". I'll wrap up this post with the closing paragraphs of the 2002 Times article:

The clocks, after all these years, still have a vexing tendency to run slow sometimes, and not even uniformly. One face can read perfect time while another lingers in the past.

Up in the control room of the clock tower recently, with Brooklyn laid out in dizzying 360-degree splendor just outside the door, the building engineer, William Harris, explained how this happens.

The four clocks run on separate motors, so there is nothing to keep them synchronized. "And sometimes," he said, "when you get a heavy wind, it can spin the hands." The hour hands, nine feet long, weigh almost 300 pounds. The minute hands are nearly twice that size. The wind is stronger. The strongest winds, Mr. Harris said, blow on the east and south sides, so those clocks have the most trouble.

As he spoke these words, at 4:16 p.m., the east clock, facing Fort Greene, read 3:58. Mr. Harris grabbed a large crank and wound the hands forward 18 minutes, undoubtedly puzzling anyone who happened to be looking up.

"That should do it," he said.

Gazing back through the rosy haze of history, we recall the Dodgers as the cherished sons of Brooklyn, a noble band of knights-errant who brought honor to the land by playing baseball the way it was meant to be played, simply for the love of the game. Representing a borough of immigrants, they integrated earlier than any other team, their fans united in adoration of stars both black and white: Jackie and Pee Wee, Campy and Gil, Newk and the Duke. When "Dem Bums" finally vanquished the hated New York Yankees and brought a championship to Brooklyn in 1955, after having fallen short against their villainous crosstown rivals in each of their past five World Series appearances, it seemed to validate the belief, later phrased so eloquently by Martin Luther King Jr., that "the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice."

And so it was with great horror that Brooklynites watched the Dodgers, the borough's heart and soul, move to Los Angeles after the 1957 season. The greed. The deceit. The betrayal! Animosity for the team's owner, Walter O'Malley, ran rampant, expressed succinctly in this old joke:

If Hitler, Stalin, and O'Malley are in a room and you only have two bullets, who do you shoot?

O'Malley, twice.

It's supposedly an old joke, anyway. You can find it repeated all over the place, but I haven't discovered a reference to it in any source published before 2000. I wonder if "memories" of the joke are just mutations of this story told in 1984's Bums: An Oral History of the Brooklyn Dodgers.

On the larger subject of historical fidelity, who knows if the Dodgers were really as universally revered, as central to Brooklyn's identity, as the old stories make it seem. They certainly had their share of die-hard fans, and attendance at their home games at Ebbets Field exceeded the league average almost every year from 1919 on, but not always to the extent you might expect. During their final five seasons, they finished in first place three times but their home-game attendance was less than eight percent above the league average, and it even dipped below average in 1957. Perhaps decades of romantic reminiscences by a generation of fans whose youths were defined by the Dodgers' presence and then their absence have warped our view of the past, transforming a fairly popular ball club into the stuff of legend.

But regardless of how grounded in reality it is, the Dodger mythos is now firmly established in the public consciousness. (Meanwhile, nostalgia for the New York Giants, who moved to San Francisco the same year the Dodgers left town, runs nowhere near as high. The Giants were the better team over the decades, with five World Series titles to the Dodgers' one, although they were less successful in the years leading up to their move. They did win the World Series in 1954, however, and they had a young man who would become one of the greatest players of all time, if not the greatest, Willie Mays, roaming center field. But their fan base, judging by their home-game attendance at the Polo Grounds, didn't quite match the Dodgers'; it probably didn't help that the eternally dominant Yankees played right across the Harlem River, one subway stop away. And being located in Manhattan, with all its iconic attractions, meant the Giants could never be as synonymous with their home borough as the Dodgers could.)

It was O'Malley's desire for a new ballpark to replace the aging Ebbets Field that drove his decision to move the Dodgers to Los Angeles. He originally had a plan to keep the team in Brooklyn, however, by building what would have been the world's first domed stadium, designed by Buckminster Fuller, on a site near the intersection of Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues. O'Malley wanted the city to use its power of eminent domain to help him acquire the land he needed, forcing unwilling property owners to sell under the premise that the new ballpark would serve the common good. His scheme would have also required heavy public expenditures on infrastructure to support the stadium. Robert Moses and other government officials were less than enthusiastic about the idea. Here's Brooklyn congressman John J. Rooney addressing the matter on the floor of the House of Representatives in 1957:

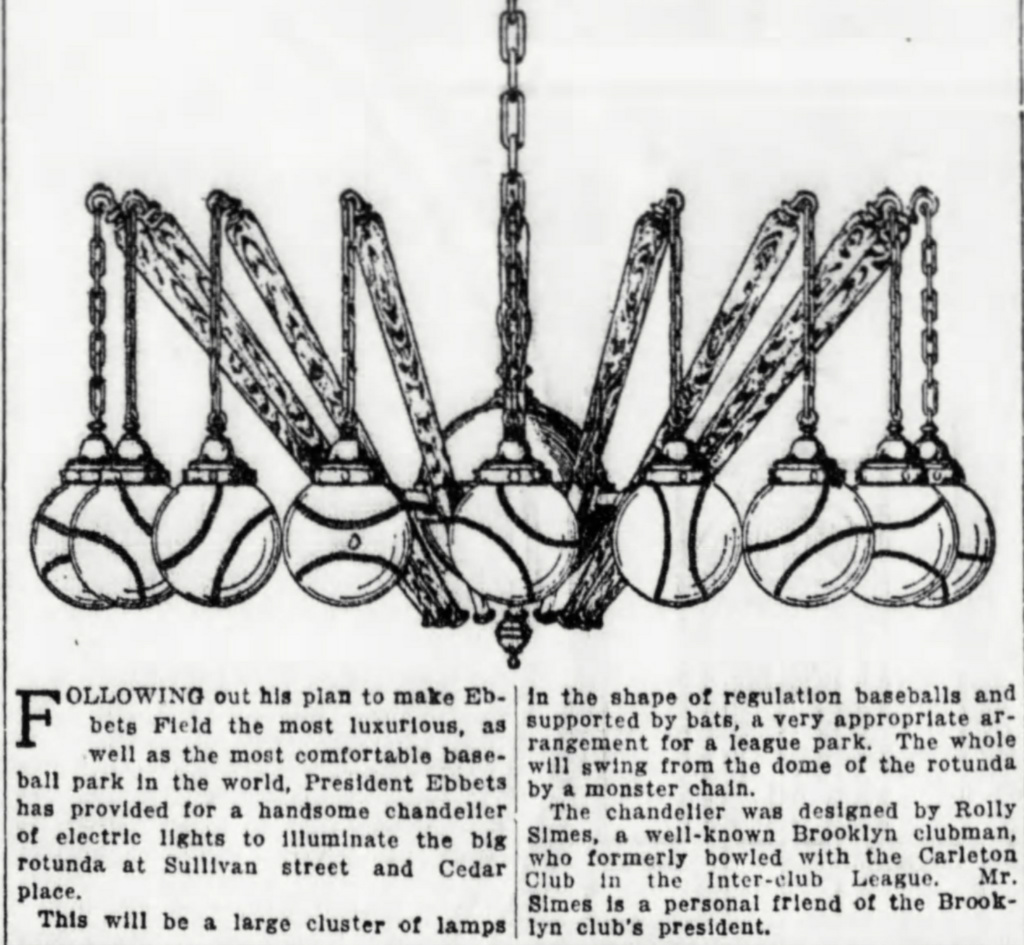

For years the Brooklyn Baseball Club has coined money for the few stockholders of its closely held stock. The owners never shared any of their profits with the fans. They took advantage of the Dodger fans at every turn . . . I say let them move to Los Angeles if the alternative is to succumb to an arrogant demand to spend the taxpayers' money to build a stadium for them in Brooklyn. I am opposed to uprooting decent citizens living in my congressional district in the vicinity of . . . Flatbush and Atlantic Avenues in order to put more money in the pockets of my dear friend Walter O'Malley and the private profitmaking Brooklyn Baseball Club stockholders. . . . Let Walter O'Malley and his stockholders who have no civic pride for Brooklyn, where they made their money, move to the west coast in quest of more almighty dollars.Ebbets Field was razed (with a wrecking ball painted to look like a baseball) a couple of years after the Dodgers left, in 1960, but numerous parts of the ballpark managed to escape destruction. After demolition began, fans were invited to come take seats for free. At an on-site auction held after most of the stadium had been torn down, a wide array of items were put up for bid, including "bats, balls, plaques, pennants, player stools, Ebbets Field sod, grand stand seats, bases, the pitcher's rubber, lockers, bricks, ushers' uniforms, pictures, electrical fixtures, bat racks and team schedules". The auction only raised about $2,300 in total, whereas you can now find many Ebbets Field seats selling online for more than that. Even a single brick can go for well over $1,000 these days.

Marvin Kratter, who purchased the stadium in 1956 and then built the Ebbets Field Apartments in its place (and who also built the Bridge Apartments — a.k.a. the Four Sisters, a name I continue to repeat in hopes it will one day catch on — above I-95 in Washington Heights), also gave away lots of stuff to be reused elsewhere. He provided 2,200 seats and some lights to furnish a pair of ball fields for workhouse inmates on Hart Island. The first game at the newly christened Kratter Field pitted the workhouse all-stars against a team of army men from the island's Nike missile battery. According to the NY Times, "the soldiers claimed seven runs in their first time at bat, but the inmate scorer and umpire said it had been only five. . . . The home side also got five runs in its first turn, but by then it was 3:50 P.M. and the game was called because it was time for the regular count of prisoners." (Here are a couple of photos from 1991 showing remnants of the seats at the abandoned fields, which have since been cleared.)

According to an article from 1961, one of the seats sent to Hart Island was subsequently "liberated", shipped across the country "by ferry, limousine and jet plane", and given to Chuck Connors, the star of TV's The Rifleman. Connors had previously enjoyed a glorious career with the Dodgers, grounding into a game-ending double play in his one and only plate appearance with the team, at Ebbets Field in 1949. (He also played 66 games for the Cubs in 1951, as well as 53 games of basketball with the Boston Celtics between 1946 and 1947.) When Ebbets was being torn down, Connors asked his agents to help him locate his favorite seat from the ballpark, K-16, so that he could have it installed at the new Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. It turned out the seat had already been taken to Hart Island, but the warden "agreed to pardon" it for Connors. Prior to the completion of Dodger Stadium in 1962, Connors used K-16 as his chair on the set of The Rifleman. I don't know if he actually succeeded in having the seat installed in the new ballpark. A photo from 1964 shows him with an Ebbets Field seat in his house, which suggests that may have been the final destination of K-16, but it's unclear whether the seat in the photo is K-16 or a different one. It has a plaque on it that reads "Last Chair From Ebbets Field, Presented To Chuck Connors By The City Of Brooklyn", while there was no such plaque on K-16 when it was photographed for the 1961 article.

Kratter sent 500 lights to Randall's Island, where they illuminated Downing Stadium. Many of the individual fixtures were swapped out for new ones over the years; I don't know what happened to the remaining original ones after Downing was torn down in 2002 and replaced by Icahn Stadium.

An outfield flagpole donated by Kratter was put up outside a Veterans of Foreign Wars post in East Flatbush. The VFW hall was later occupied for many years by the Canarsie Casket Company, and the flagpole remained standing until around 2007, when a church that had acquired the property began work to expand the building.

Marty Markowitz, Brooklyn's borough president at the time, heard about the flagpole coming down and alerted his buddy Bruce Ratner, who arranged to purchase it from the church. Ratner was the driving force behind the massive Atlantic Yards development (now called Pacific Park) that is, and will be for many more years, under construction in Prospect Heights. He and Markowitz, the cheerleader-in-chief for Atlantic Yards during his time in office, had the flagpole erected outside Barclays Center, the centerpiece of Atlantic Yards and the first of its buildings to be completed. They dedicated the pole in late 2012, after the arena had premiered as the new home of the NBA's Nets and been announced as the future home (for a few seasons, anyway) of the NHL's Islanders.

(News coverage of the flagpole, as well as the plaque on its base during its East Flatbush days, identified it as the center-field flagpole from Ebbets Field. If you look at old photos of the stadium, you'll see there was in fact a flagpole above center field, one of several located on the roof, but these poles look smaller than the Barclays pole to me. I suspect the Barclays pole is actually the larger flagpole that stood prominently in right-center field beside the scoreboard, capped with a ball finial that appears to match the one atop the Barclays pole.)

So why buy a flagpole from an old baseball stadium and put it outside a basketball arena? Well, Ratner and Markowitz surely understood the lure of the Dodgers — Markowitz was kind of obsessed with the team himself, in fact — and they were never hesitant to remind people that, as mentioned in seemingly every article written about the Nets' move from New Jersey, Atlantic Yards was bringing major professional sports back to Brooklyn for the first time since the Dodgers left, something Markowitz had been talking about doing since his first successful campaign for borough president in 2001.

Markowitz was also on hand at Barclays Center a few months after the flagpole dedication for a presentation of the Dodgers' 1955 championship pennant before a Nets game, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the opening of Ebbets Field. The pennant has a very funny history, having been stolen from the Dodgers in Los Angeles in 1959 by a group of four sportswriters who decided it belonged back in New York. Coincidentally, when the pennant was originally displayed for the fans at Ebbets Field during the 1956 season, it was flown from the scoreboard flagpole, the one that (I believe) now stands outside Barclays Center.

(Of course, the Atlantic Yards crew was just the latest in a long line of profit-seekers trying to co-opt some of the Dodgers' warm fuzzies for their own purposes. When the New York Mets opened their new ballpark, Citi Field — named, like Barclays Center, for a scandal-tarred banking giant — back in 2009, "some of the team's fans complained loudly that the stadium, with its extensive tribute to Jackie Robinson and its architectural nod to Ebbets Field, seemed to be more focused on the Brooklyn Dodgers' history than on the Mets'.")

But beyond the obvious Brooklyn sports connection, there's another, subtler tie between Atlantic Yards and the Dodgers. Barclays Center sits right across Atlantic Avenue from the site that Walter O'Malley wanted for his dome. And like O'Malley's quest for a new stadium, Ratner's push to build Atlantic Yards was inevitably going to be controversial. It wasn't just that the 22-acre megaproject would dramatically reshape the neighborhood; it's that, as with O'Malley's plan, it would require loads of taxpayer funds and the seizure of private property to do so. But this time, with Ratner promising all sorts of affordable housing and new jobs in addition to a sports venue (developers are often better at promising than developing), the government has been on board all the way, forcing out residents and offering more than $700 million in public financing to help make the project a reality.

So if you're Bruce Ratner, and you're trying to show everyone that all the subsidies and tax breaks are beside the point, that you and the Russian oligarch you sold the Nets to are really all about serving the people and bringing joy to the masses, then it certainly couldn't hurt to take an old remnant of Ebbets Field, a physical reminder of the sainted Brooklyn Dodgers, put it up as a public monument with your name on it, and then hold a ceremony for it with Jackie Robinson's daughter in attendance.

And could there possibly be a more appropriate place to pay tribute to a team remembered as the embodiment of all that is good and pure in sports than here at — yes, these are real names — the Resorts World Casino NYC Plaza, opposite the GEICO Main Entrance of Barclays Center?

Postscript

The aforementioned ridiculously named plaza outside Barclays Center has taken on new life in 2020 as a community hub for protestors in the aftermath of George Floyd's murder. On the evening of June 2, demonstrators raised a Black Lives Matter flag up the Ebbets Field pole. In response, someone on Twitter shared the following words written by Jackie Robinson in his autobiography, made all the more poignant when you consider that Jackie, an Army veteran who was once court-martialed after refusing to move to the back of a bus, must have laid eyes on the American flag hanging from this pole countless times during his baseball career: "I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world."