to Green-Wood Cemetery. This is the mausoleum of gun-maker William J. Syms.

DeRobigne Mortimer Bennett, a freethinker and founder of The Truth Seeker, was sentenced to 13 months in prison in 1879 at the age of 60 for violating the Comstock laws by distributing a supposedly obscene essay entitled Cupid's Yokes, a 23-page, densely worded, heavily footnoted argument against the institution of marriage. Anthony Comstock, the crusading postal inspector and head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice, personally collected the evidence for Bennett's conviction, ordering the essay from him by mail along with some other publications.

You can read Cupid's Yokes here. If it seems shocking that such an essay was labeled obscene and that distributing it could have landed you in prison in the United States just 135 years ago, keep in mind that our modern ideas of free speech still needed another 80 years to really take root; it was only a 1959 lawsuit over the Post Office's confiscation of uncensored copies of Lady Chatterley's Lover that, "in effect, marked the end of the Post Office's authority — which, until then, it held absolutely — to declare a work of literature 'obscene' or to impound copies of those works or prosecute their publishers . . . [and] established the principle that allowed free speech its total victory."

I found an NY Times article from 1883 reporting that Bennett's friends wanted to install the monument you see above here at Green-Wood, adorned with quotations from some of his writings. The Times's (or at least the author's) disdain for Bennett's countercultural views is glaringly obvious: the article describes him as a semi-literate buffoon "addicted to obscenity" whose defining thought on religion, amidst the "blasphemous and indecent rubbish that he wrote in his life-time", was "There ain't no God". Bennett's own words, however, paint a much different picture. Engraved in the monument above (though not visible in this photo), for example, are the following lines:

I believe in the eternal powers and principles of nature, in the superiority of good lives, in acts of kindness toward our fellow-beings, and in efforts to spread the light of truth over the dark spots of the earth. Each person must be responsible for the good or ill he does. Here is our duty, here is our allegiance, and not in the sky above us. We must make our heaven on the earth, and not in the air.

Back in October, we learned about "what is commonly known as the Park Slope plane crash, a 1960 mid-air collision of two airliners that sent one hurtling into Park Slope [in Brooklyn] and the other into Miller Army Airfield in Staten Island, killing all 128 people aboard, as well as 6 people on the ground in Park Slope." It was the deadliest accident in aviation history at the time it occurred.

In August 2010, just a few months shy of the 50th anniversary of this tragedy, the archivist here at Green-Wood discovered that United Airlines (one of the airlines involved in the collision) had purchased a plot in the cemetery about three weeks after the crash and had interred three caskets of unidentified human remains in an unmarked grave. After learning of this, the cemetery staff managed to design and construct a memorial near the grave site in time for the 50th anniversary that December, consisting of "a grove of one hundred Quaking Aspen trees, alcoves, benches, and a path" (photo), as well as the monument above.

This hillside crypt looks like it was sealed up long ago, but the marker in front was presumably installed within the past decade during Green-Wood's massive volunteer-fueled effort to identify every Civil War veteran in the cemetery. Here's a little background on Mr. Carville, and here's a photo of him taken during the war.

After falling from a horse-drawn streetcar as a teenager in 1865 and being dragged behind it for almost a block, losing consciousness, Ms. Fancher spent the remaining 50 years of her life confined inside her home, where she became "hugely famous" as the "Brooklyn Enigma". According to a Salon review of a book about her:

Mollie fell into a trance (an elaborate escape, perhaps, from her physician’s ineptitude?) that lasted for nine years. But she was hardly comatose. Indeed, she was a regular Martha Stewart. While in her altered state she "wrote more than six thousand five hundred letters, worked up one hundred thousand ounces of worsted, did a vast amount of fine embroidery, and constructed a great number of decorative wax-work flowers and leaves." Meanwhile, she started communing with the dead, having out-of-body experiences, "seeing" with her forehead and her fingertips rather than with her eyes and channeling five "other Mollies" — named Sunbeam, Idol, Rosebud, Pearl and Ruby. But Mollie's real claim to fame was her astonishingly meager diet. To the end, Mollie and her caretakers maintained that for 12 years she ate nothing more than four teaspoons of milk, two teaspoons of wine, one small banana and one cracker. The very picture of Victorian refinement, she "lived on air."(Other accounts I've read offer some conflicting details, but the gist of the story is always the same.)

This vicious ball of spikes is a trifoliate orange plant. (Several of these "shrubs were planted in the 1960's inside the fence at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden in a successful effort to discourage trespassers"). The little citrusy fruits smell wonderful, but they're packed full of seeds and are extremely sour.

IN MEMORY OF

JAMES WALL FINN

THROUGH WORKS OF BEAUTY

AND THROUGH GENEROUS DEEDS,

HE SHAPED HIS LIFE

AND ART TO GOLDEN ENDS.

HE PLUCKED THE FLOWER

OF LOVE BUT LEFT ITS SEEDS

TO BEAR NEW BLOSSOMS

IN THE HEARTS OF FRIENDS.

James Wall Finn was a Tiffany Studios artist, and his headstone is the work of Frederick MacMonnies, who was almost buried here at Green-Wood himself: his grave had already been dug when his wife decided at the last minute to have him interred elsewhere. MacMonnies also sculpted the semi-controversial Civic Virtue, which has been moved from its former spot outside Queens Borough Hall since we last saw it. Where did it end up? Here at Green-Wood! It was only after the cemetery's initial failed attempt to acquire Civic Virtue from the city in 2011 that Green-Wood's president discovered, through a chance encounter with a MacMonnies expert, that Finn's stone is also a MacMonnies creation!

Considered by many to be baseball's first superstar, Creighton revolutionized the role of the pitcher and gained mythic status when he supposedly suffered a fatal injury while hitting a home run in 1862 at the age of 21.

Joseph Scavone

Born in 1949; died in 1980

Vietnam veteran

I'm not exactly sure what needs a power source here. There's something with wires coming out of it (photos: front, back) at the heart of the cross; perhaps there is (or was) a light there? Here's a closer look at the solar cells.

This figure of Azrael (there's actually a face inside that cloak), sculpted by Solon Borglum (whose brother who carved Mount Rushmore), marks the graves of Charles A. Schieren, mayor of Brooklyn from 1894-1895, and his family. The NY Times ran a very flattering profile of Mr. Schieren in October 1893, just a couple of weeks before his election. The final paragraph reads:

Mr. Schieren is above the average in size, and well built. He has a pleasant face, with regular, clear-cut features and kindly brown eyes, which leave an impression of sincerity upon all who meet their gaze. His brown hair is sprinkled with threads of gray, as are also his luxuriant side whiskers and mustache. In manner, he is kindly and good-natured, and is a man whom it is a pleasure to know.

I believe this monument is supposed to represent a fireman's trumpet; there is also a sculpture of a firefighter's helmet on the ground beside it.

The cemetery's description of this community mausoleum reads a lot like a luxury apartment listing:

A dramatic, modern work of architecture nestled in the slope of a hillside. Cascading shingles of glass sheath the front of the mausoleum, which overlooks the pastoral landscape of historic Green-Wood Cemetery. . . .

Intimate groupings of bentwood settees and club chairs encourage visitors to sit and meditate in peaceful comfort. Indian slate floors underlie sumptuous Tibetan wool carpets with natural motifs of water, bamboo and leaves.

Granite and marble crypts in warm hues of almond mauve, silver sea green and gold-flecked deep green are four high for a more personal reflective experience. Opaque or clear glass and “memory box” wood niches for cremated remains in the columbaria provide a choice of elegant memorialization options.

A five-story blue waterfall under each of two pyramid skylights ripples gently over an undulating surface before collecting in a water garden at its base. Reflecting pools offer a contemplative area at the mausoleum’s entryways. An airy Brazilian hardwood and steel interior stairway in each light-filled atrium unites ground floor with hilltop . . . Tranquility awaits at each level.

David A. Boody briefly held a seat in Congress and preceded Charles Schieren as mayor of Brooklyn, serving in that position from 1892-1893.

Henry Ward Beecher (brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe) was "probably the best-known Protestant minister in the United States", and the trial over his alleged affair with a married congregant enthralled the nation. (We previously passed by a building named in honor of William M. Evarts, his senior counsel during that trial.)

That's the title of this sculpture installed in front of the tomb of Henry Bergh, who founded the ASPCA in 1866 and who "alone, in the face of indifference, opposition, and ridicule," worked to bring an end to the many barbaric acts of animal cruelty once seen as acceptable. The sculpture originally hung on the side of the ASPCA headquarters in Manhattan; it was moved here in 2006.

by Adolfo Apolloni. You can see some beautiful shots of this statue from different angles here.

Samuel Chester Reid, a naval hero in the War of 1812, was "a principal actor" in the 1818 redesign of the American flag and in establishing the template for all future flags: thirteen stripes (one for each of the original states), along with one star for each current state. The 20-star flag he designed in 1818, one of which (sewn by his wife, according to his gravestone) was flown over the Capitol for at least part of that year, had its stars arranged in the shape of a larger star (a "great luminary"). Later in 1818, the Navy dictated that US flags flown on its ships and at its installations would have their stars laid out symmetrically in even rows; it's one of these 20-star flags that can be seen flying over Captain Reid's grave here in Green-Wood.

Imre Kiralfy memorial. Mr. Kiralfy, a noted producer of extravagant theatrical spectacles, was originally buried in London after his death in 1919, but his wife later had him cremated and moved to this mausoleum.

The "Father of Baseball" is one of four men known by that title buried here in Green-Wood, which the NY Times called "the final resting place not only for a Who's Who of baseball heroes and dignitaries of the 19th century but also for dozens of other trailblazers of the sport." Mr. Chadwick's monument apparently had some basepaths running around it not too long ago.

278 (or more) people died in a fire at the Brooklyn Theatre in 1876; 103 of them, "whose remains were so charred that they could not be identified, whose bodies were unclaimed, or whose family could not afford private burial, were interred together" here in Green-Wood.

of Currier and Ives, the famed 19th-century printmaking firm. Ives is also buried here in Green-Wood, as are a number of artists that the firm employed.

From the NY Times:

They were bullish on America, and America loved them. For half of the 19th century, their pictures, many of startling immediacy, chronicled the dreams and catastrophes, cityscapes and landscapes, heroes and villains and everyday events of a young, muscle-flexing nation. Before photographs made Currier and Ives obsolete, at least one of their lithographs had found its way into virtually every home in the country.

DeWitt Clinton, a former US senator, NYC mayor, and New York governor, is probably best remembered as the driving force behind the creation of the Erie Canal. He was buried elsewhere after his death in 1828, but Green-Wood, which was struggling in the early years after its 1838 founding (the idea of large rural cemeteries apparently hadn't yet caught on with the public), convinced his son to reinter him here in the 1840s in the hope of bringing prestige to the cemetery and portraying it as a desirable place to be buried.

The monument above was dedicated in 1853, featuring a large statue of Clinton (the "second oldest surviving heroic bronze cast in America") wearing both 19th-century garb and a Roman toga, as well as two scenes sculpted in relief on the plinth. The scene on the opposite side (close-up) illustrates what I assume is the construction of the Erie Canal. I'm not sure what the relief above (close-up) is supposed to depict, however. At first, I thought those horses might be towing the ship in the background through the canal, but all the other figures gathered around them make that seem unlikely. And the family on the left is particularly perplexing — what's with the shoes?

Henry Draper, son of the distinguished John William Draper, was a doctor and a pioneer of astrophotography. The circular objects adorning his monument depict the two sides of the gold medal produced in his honor by the Philadelphia Mint at the order of Congress to memorialize his role in photographing the 1874 transit of Venus.

The Draper name is largely forgotten today, but, if Henry's obituary in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle is any indication, the Drapers were highly revered in the scientific community at the time of his death in 1882 at the age of 45 (following his father's death earlier in the year). I've included some excerpts from the obituary below; the final paragraph also offers perspective on an American inferiority complex that may have existed at the time.

The cause of scientific study not only in the country but throughout the world has suffered severely during the year that is now drawing to a close. The death roll of the past twelve months has included many illustrious names, that of Mr. Darwin heading the list, to be quickly followed by that of Professor [John William] Draper the elder. Now within a few months Henry Draper the younger has died suddenly after carving out for himself at a comparatively early age a record well worthy of the illustrious name he bore. The decease of these two eminent men is a sad blow to the cause of science and to the millions of people who benefit by the tireless energy, the dazzling versatility and intelligent persistence of the thinking few. . . .

It does not often happen that genius is bequeathed from father to son, but in the case of the Drapers the intellectual vigor of the parent was reproduced in the son, who at a very early age launched out into scientific study and achieved results undreamed of by older and less exuberant minds with the same versatility and originality which marked the elder . . .

Indeed through the Drapers and a few others we have been enabled to wipe out the reproach put upon us [as a nation] by a friendly critic some thirty years ago, that we had not shown the least capacity for art or science. It is true that we have not yet produced any large triumphs of art, but we have at least developed an art spirit which must before long express itself. In some departments of science, the speculative for instance, we are yet behind England, France and Germany, but in the applications of science we are almost equally ahead. . . . though we cannot but realize that a prophet and the son of a prophet has been removed from the arena of this world's activities we may rest assured that the impulse given to the study of knowledge for its own sake by father and son will not cease, but rather tend to increase.

We're looking out across (a small portion of) Green-Wood toward the waters of New York Bay. The beautiful building at the bottom of the hill is the cemetery's chapel, a smaller version of Christopher Wren's Tom Tower.

It always surprises me to see a big, stately courthouse built in an outlying neighborhood like Sunset Park rather than, say, Downtown Brooklyn, but there were actually quite a few local courthouses spread around the city before a 1962 reorganization centralized the court system.

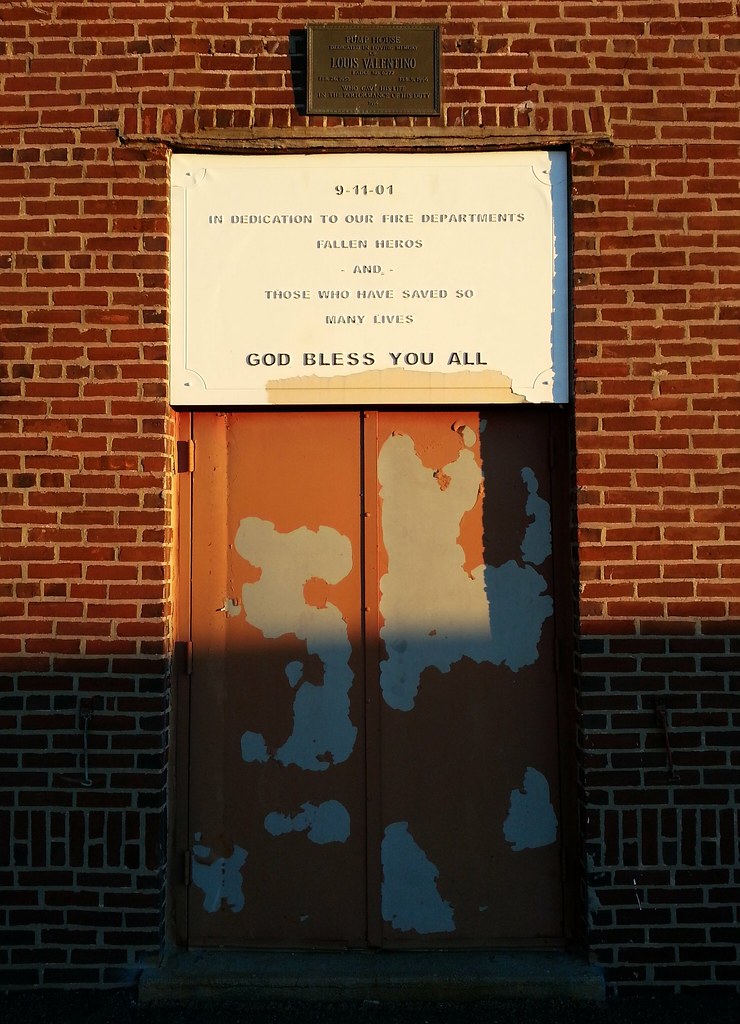

This is the Bush Terminal pump house, which, according to the plaque above the memorial, is dedicated to Louis Valentino.

I've walked by enough botánicas to know that something's off here. They took away his sword and replaced Satan with a rock!

This "striking [example] of late 19th-century civic architecture", with its "chaotic variety of decorative forms: a corbeled parapet of rounded brick, rope moldings of terra cotta, zigzag and Romanesque carving, rock-faced brownstone and decorative ironwork", originally housed the 18th Police Precinct (which was subsequently renumbered many times, becoming the 43rd, 143rd, 76th, 32nd, and, finally, the 68th Precinct). The architecture was meant to intimidate potential wrongdoers; at the building's dedication in 1892 (covered by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle with the subheading "Where Gallant Policemen Will Often Pass With Just Pride, but Where, Probably, Many a Poor Wretch Will Leave Hope Behind"), the Brooklyn police commissioner said: "A man about to commit a crime would stand appalled at the sight of a station house such as this is."

The precinct moved to a new station house in 1970, and the building has largely been left to deteriorate for many years now, despite being designated a city landmark in 1983. You can see some photos of the interior and the adjoining stable here. Back in February, we passed by a very similar decrepit old station house, designed by the same architect, out in East New York.