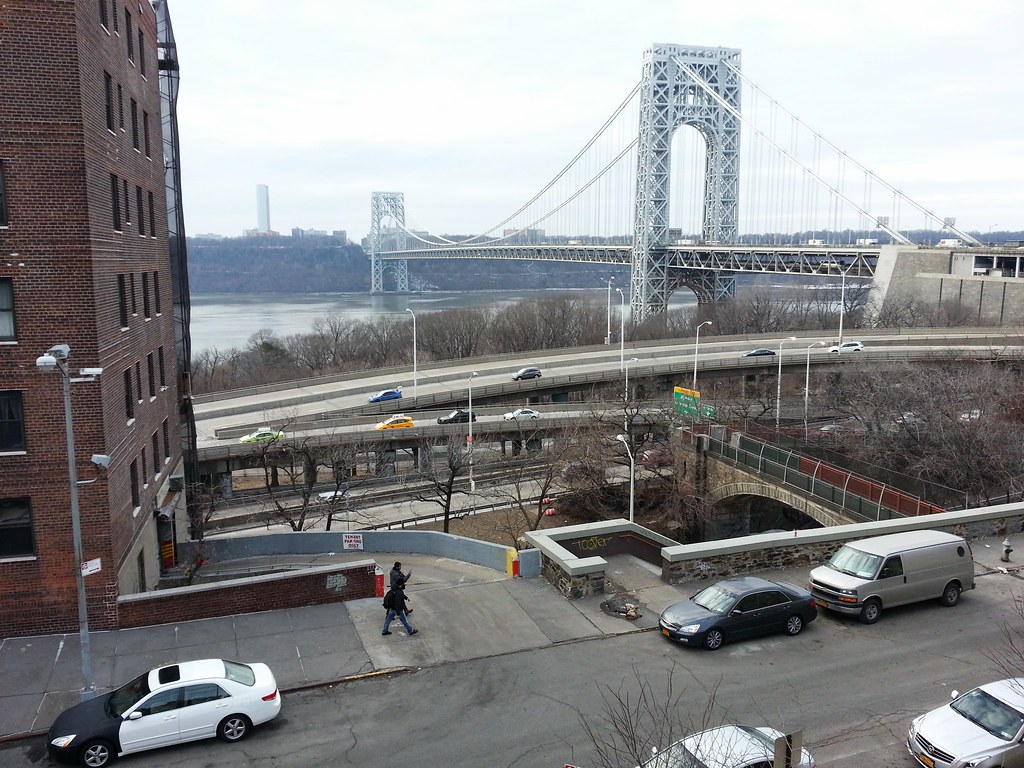

The north pedestrian path (pictured) on the George Washington Bridge was closed today, while the south one was open. That's been the case every single time I've walked over the bridge, with one glaring exception.

Not the first one we've seen.

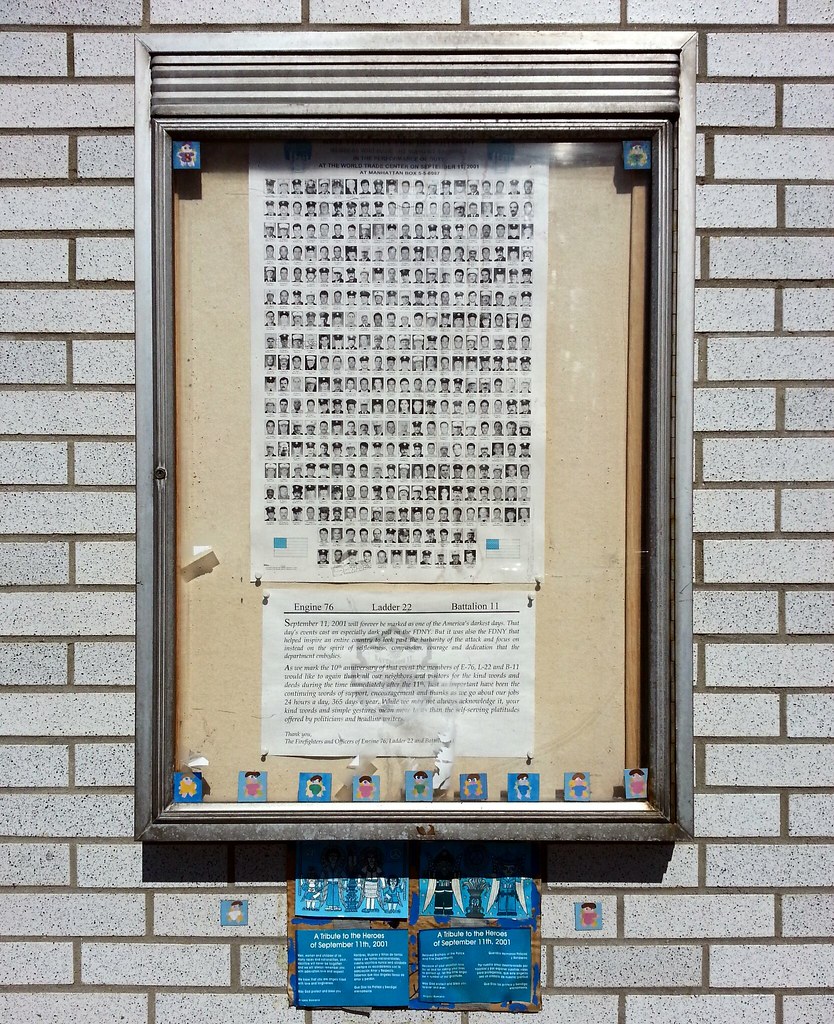

This is on the New Jersey side of the GW Bridge, so it doesn't count in the official tally of NYC 9/11 memorials.

Notice how tiny the Little Red Lighthouse looks next to the George Washington Bridge.

Opened in 1963, this bus terminal — or "concrete butterfly" (aerial view) — was the first structure in the US designed by Pier Luigi Nervi. Like the four towering apartment buildings directly to its east, it was built on top of the Trans-Manhattan Expressway.

Ada Louise Huxtable wrote that this former off-track betting parlor in the George Washington Bridge Bus Station "occupies the most space on the concourse and exudes an air of abandoned hope" — and that was before it closed down in late 2010, along with all the others in the city. To quote a post from two years ago:

After struggling for years, all the NYC OTB parlors were finally shuttered in late 2010. A considerable number of them, however, have managed to eke out a pathetic sort of survival, courtesy of the sluggish economy: their signs and logos, or at least traces of them, still adorn many of the vacant, unrented storefronts that once housed the parlors. The former customers, of course, have had to move on, but what has become of Jesus Leonardo? Not to worry, friends: he just keeps on keepin' on.

When it opened in 1920, the Coliseum (photos) was the city's third-largest theater, a 3,500-seat movie and vaudeville house. It was still showing films as recently as 2011, although it had become a multiplex by that point, with a good chunk of the original theater converted into retail space.

The program from the Coliseum's opening night is available online. It contains several pages of historical information, and even a little social commentary:

Eighteen hundred years ago, the people of the greatest city of that day came to another Coliseum for their "entertainment." The Romans loved a welter of blood. Slaughter was sport. Gladiatorial combats were recreation for the Emperors, the aristocrats and the mob.The program goes on to claim that the theater occupies the former site of "the famous old Blue Bell Tavern, teeming with memories of Colonial days, Revolutionary days, and days when the Republic was young", where "scores of the most celebrated statesmen, diplomats and soldiers America ever produced . . . once had their 'nips' and their beverages prepared for them". For, you see, "the Blue Bell was no ordinary hostelry, where drinks were sipped only by citizenry of low repute and no standing. The Blue Bell was distinctly a tavern with a lineage."

"Entertainment?"

We sit in a magnificent palace, luxuriously appointed, and laugh. But we have only lately done with the most murderous war in the history of civilization.

"Civilization?"

Perhaps the Romans laugh.

That all sounds a bit overblown, but the Blue Bell was indeed a well-known tavern in then-rural northern Manhattan. It was notable enough that the Museum of the City of New York crafted a small-scale replica of it, "re-created in wax, perfect in even the smallest detail", for a historical exhibit in 1930. And it did stand somewhere around the present-day intersection of Broadway and 181st Street (pictured above), although sources vary on its exact location.

There are two great tales of romance, in which love triumphs over wartime allegiances, that took place at the Blue Bell during the Revolution. The first occurred in the early days of the war, after the Americans had been driven out of Manhattan. Colonel Johann Rall (or Ralle), a commander of German troops fighting for the British, made the Blue Bell his headquarters. And that's when things started to heat up...

[The tavern-keeper] had a pretty sister, whose charms smote one of Ralle's aides so powerfully, that he proposed marriage within twenty-four hours after they first met. He was a fine-looking young Anspacher. He promised to remain in America when the war should be over, and vowed eternal fidelity to her. The maiden's heart was touched, first with sympathy, which speedily became transformed into the tender passion. Her mother consented to the marriage, but her brother stormed. The gallant Ralle, who had passed through a similar experience in his own country, favored the union, and on the evening before his departure from the Blue Bell, the lovers were united in marriage, in the secrecy of the colonel's room, by the chaplain. The bride followed her husband in the chase of Washington across New Jersey, and the young Anspacher was slightly wounded, and was made a prisoner when his commander fell at Trenton. Refusing to be exchanged, he took the oath of allegiance to the newly-declared republic at Morristown, and settled in East Jersey, where many of his descendants are now living.The second story was recalled in the mid-1800s by Major Robert Burnet, at that time a 90-year-old veteran whose "mind was clear, and [whose] memory of the events of his earlier life was marvelous." At the end of the war, after the Treaty of Paris had been signed and the British were preparing to leave the city, the Americans had re-entered Manhattan and were marching south past the Blue Bell...

Just as the rear-guard had filed past the tavern, a young man, in the uniform of a British soldier, and followed by a modest-looking young woman, rushed out and beckoned to [General George] Washington vehemently. The chief halted, when the young man, in great perturbation of mind, said he was a deserter from the British army, and implored protection. He was placed in charge of Major Burnet, who took the refugee to his quarters. There he learned that the young man was a sergeant . . . who had for some time loved and was betrothed to the young woman who was with him; that her parents, who lived in the city, would not consent to her marriage unless he would stay in this country; that [the couple] had arranged a plan a few days before for a desertion on his part and an elopement on hers; that they were to meet at the Blue Bell and be married, and there wait for the protection of the approaching American troops. Their plan had worked well. She, on pretense of visiting an aunt at Bloomingdale, had made her way on foot to the Blue Bell. He had managed to escape the sentinels at the unfinished hospital, on Broadway, in the darkness of a rainy night, and, under its shadow, had also made his way to the Blue Bell, where they had been married, the day before, [in the clergy-less style] of the Quakers, by declaring, in the presence of witnesses, that they took each other for life companions, as man and wife. He showed Major Burnet their marriage certificate, signed by half a dozen witnesses. The major provided for them that night, and the next day they accompanied the troops into the city. . . .When these two love stories were told in the pages of Appletons' Journal in 1873, the author summed them up with an unintentional pun that wouldn't take on its second meaning for almost half a century, until the Coliseum was built on or near the site of the tavern: "Twice, at least, the Blue Bell has been the theatre of a clandestine marriage."

A bard in Major Burnet's corps composed a number of verses on the occasion, of which the following are all that the veteran remembered:

" A soldier and a maiden fair,

Helped by shy little Cupid,

Fled from the camp and mamma's chair,

(Such guardians, how stupid!)

And to the Blue Bell did repair,

To have themselves a-loopèd

" In silken cords by Hymen's hand.

A parson there was lacking;

So in the Quaker way they wed.

The bond was signed. Then, smacking

each other as a nuptial pledge,

They waited for the backing

" Of our brave troops, for Sergeant M—

Was fearful of a banging

By British guns, should he be caught—

Perhaps a dreadful hanging."

That's the Washington Bridge (which is different from the George Washington Bridge) on the left and the Alexander Hamilton Bridge on the right.

This building opened in 1913 as the Mount Morris Theatre. The following year, four local burglars were arrested after cleaning out a nearby tailor shop and stashing the stolen goods in the theater. A cop spotted the theft in progress and followed the men back here, imitating a stumbling drunkard so as not to arouse their suspicion. After other officers arrived on the scene, the police raided the building. The thieves attempted to escape, but the cops pursued them through the theater, "even into the fly loft, jumping and swinging through space like a bunch of bats."

A few years later, according to a piece in Cigar Aficionado written by Groucho Marx's son, a preteen Milton Berle got an early career break here when he was hired to appear with Irving Berlin one evening, singing Mr. Berlin's "Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning" from a box beside the stage, skirting a child labor law that prohibited children from performing on stage at night.

As World War I was raging, the newly formed Institutional Synagogue began meeting here. In a speech at the synagogue in 1918, not long before the passage of the Sedition Act, Congressman Julius Kahn said he had been informed that many neighborhood residents were opposed to the war. He then "told [the] large audience . . . that immediate and direct measures must be taken by the Government to silence all individuals and organizations that raise their voices against the war", exclaiming to the cheering crowd:

"When a seditious or traitorous voice is raised here . . . I hope the hand of the law will reach out and grasp the speaker. I hope that we shall have a few prompt hangings, and the sooner the better. We have got to make an example of a few of these people, and we have got to do it quickly."At the end of 1919, the theater reopened as a burlesque house. By 1932, "it was featuring Latino stage and musical performances", and continued operating as a series of Spanish-language theaters, most notably El Teatro Hispano, until at least the mid-1950s. You can see a 1934 drawing of the building here.

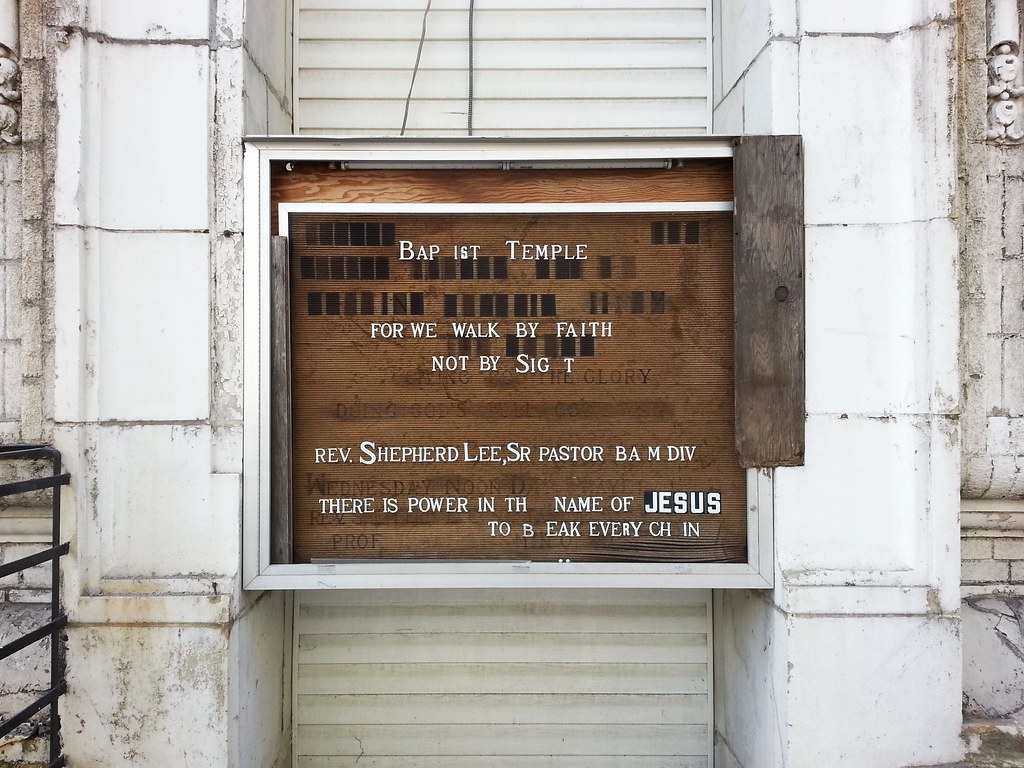

Built in 1906, today's Baptist Temple was originally home to Congregation Ohab Zedek (photo), which in 1912 "thrilled worshipers" by hiring the renowned European cantor Yossele Rosenblatt. (Last year we passed by Congregation Anshe Sfard, where Mr. Rosenblatt was later employed.) The following "classic Rosenblatt shtick" shows the great regard in which the famed tenor (a few of whose recordings you can listen to here) was held:

A young cantor billed himself as "The Third Yossele Rosenblatt."In 2009, concerns about the building's structural stability led to part of its facade and roof being torn down. Google Maps has a cool new feature that allows you to see all the Street View images taken at a certain place over time; you can use it here to see what the Baptist Temple looked like before its partial demolition and during its subsequent reconstruction.

"And who," he was asked, "was the Second Yossele Rosenblatt?"

"Feh!" he replied in disgust, "Everyone knows there could be no Second Yossele Rosenblatt!"

The Kalahari condominium, with a facade "inspired by South African Ndebele tribal designs"

Andrew Haswell Green was "arguably the most important leader in Gotham's long history, more important than Peter Stuyvesant, Alexander Hamilton, Frederick Law Olmsted, Robert Moses and Fiorello La Guardia", accordingly to the historian Kenneth Jackson. He was the driving force behind the creation of the modern five-borough New York City in 1898, and he was also a key figure in the establishment of several of New York's most notable institutions: Central Park, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Museum of Natural History, the New York Public Library, and the Bronx Zoo, not to mention the Washington Bridge and Riverside, Morningside, and Fort Washington Parks. An NY Times piece published late in his life recounted these accomplishments, as well as others "in the same general line, pursued with the same longsightedness and the same steadfast fidelity to a high standard of public service and personal conduct, so that in his ripe age no member of this vast community more richly merits the honorable title of Citizen of New York."

He was a man of great integrity (that makes two now!), and while he may have been "an imperious skinflint", "overbearing and stingy", and certainly "not the kind of guy you'd party with", his sober frugality was a much-needed virtue in the halls of government. Appointed city controller in the aftermath of the Tweed Ring scandals, he helped rescue New York from financial ruin at a time when "the city and county finances [were] in confusion . . . the Treasury empty, the city's credit seriously impaired, taxes excessive, the debt swollen beyond all precedent, city laborers and employes clamoring for pay, public institutions without funds to feed the hungry mouths of their wards, and the public buildings, markets, streets, and docks dilapidated and despoiled." Reflecting the regard in which he was held, the New-York Tribune wrote of his appointment at that dark hour: "The man who now holds the keys of the City Treasury is incorruptible, inaccessible to partisan or personal considerations, immovable by threats or bribes, and honest by the very constitution of his whole nature."

But despite the deep impact he had on the city's development, Mr. Green is largely unknown today. More than a century after he was murdered in 1903 in a bizarre case of mistaken identity, this hilltop bench in Central Park was the lone public monument to his life and work. (An "award-winning statue" of the man was created for the city's Golden Jubilee in 1948, but was never put on permanent display and ended up relegated to a garage in Maine.) And if that weren't enough of a slight on its own: the inscription on the bench states that "this eminence was named Andrew H. Green Hill", but the bench was booted off said eminence and relocated here in the 1970s or '80s to make way for a composting operation. Thanks to the tireless efforts of Manhattan borough historian Michael Miscione, however, the city has finally decided to honor "the Father of Greater New York" with something a bit more prominent: a waterfront park on Manhattan's East Side in the shadow of the Queensboro Bridge. (Now we just have to hope it doesn't fall into the East River.)

An even better honor would have been one Mr. Miscione was specifically pushing for: renaming the Washington Bridge after the master planner who first proposed building it. Rechristening the beautiful but often overlooked Harlem River span would not only be a more fitting and more conspicuous way to remember this forgotten civic hero, it would also help clear up a particularly confusing aspect of Upper Manhattan's transportation infrastructure: there are three vehicular bridges in close proximity to each other around 180th Street, and two of them are named after George Washington! Even Google can't keep things straight, labeling the lanes of the Washington Bridge with the name of its much more famous Hudson River counterpart, the George Washington Bridge.

So let's hear it for the Andrew H. Green Memorial Bridge — bringing recognition to a great public servant and clarity to our city's bridge nomenclature all in one fell swoop!

It was . . . in June 2005, that residents of the Upper West Side got their first glimpse of the two glass-sheathed towers that were to rise on Broadway at 99th Street. The local community board was having its monthly land use meeting — not generally an occasion of high drama — and Gary Barnett, president of the Extell Development Company, came to share renderings of his proposed buildings. As he unveiled them, a gasp was heard throughout the room. "People shrieked," recalls Sheldon Fine, chairman of Community Board 7.Dwarfing their surroundings, these two soaring apartment towers, Ariel East (pictured) and Ariel West, were controversial additions to the skyline of the Upper West Side. The community board was so upset by the enormity of the structures that it pushed through a rezoning plan to limit the height of future buildings in the area. (Somewhat ironically, of course, these height restrictions also effectively protect the commanding views currently enjoyed by those residing on the upper floors of the Ariels.)

What caught my eye, however, was not the height of the pictured building, but the glaring sheet of reflected sunlight it was casting on, and through the windows of, the building to its south (closer look) — which certainly can't be helping it endear itself to the neighbors.

Constructed in 1898, this building was originally the Bloomingdale Branch of the New York Free Circulating Library. It became part of the New York Public Library when the two systems merged in 1901, and it continued serving as a branch library until 1960. Since 1961, it's been home to the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., with part of the space fittingly used to house the academy's research library.

Dedicated to the fallen "soldiers in a war that never ends", this 1913 monument on Riverside Drive has long been the site of an annual ceremony commemorating city firefighters who lost their lives during the previous year. There is also now a memorial service held here every September 11th to pay tribute to the 343 members of the FDNY who were killed on 9/11.

The diamond-shaped plaque embedded in the bricks in front of the memorial, dated 1927 and "subscribed under the auspices of the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals", reads:

THIS TABLET IS DEDICATED

TO THE HORSES THAT SHARED

IN VALOR AND DEVOTION

AND WITH MIGHTY SPEED

BORE ON THE RESCUE

Happy Warrior Playground, named for Al Smith, a four-term governor of New York and the 1928 Democratic presidential candidate

a.k.a. Goat Park or The Goat, home of the Goat Courts

a.k.a. Rock Steady Park, former hangout of the Manhattan chapter of the Rock Steady Crew (video)

Completed in 1914, 780 West End Avenue was designed "in a radically different style from other apartment houses of the period" by the brothers George and Edward Blum, who "formed one of the city's great nonconformist architectural firms". You can see more photos of the building here.

Here we have another magnificent bank turned CVS, this time with a private preschool located in the building as well.

On April 4, 1932, two days after the ransom for the Lindbergh baby kidnapping was paid, a teller at this Upper West Side bank branch made the first discovery of a ransom bill that had been spent. Hundreds of the bills would later be identified in bank deposits, but it took almost two and a half years before the case was finally cracked open, when a ransom bill was found — at a now-abandoned bank in Harlem we saw last summer — with the license plate number of the man who passed it scribbled in the margin by a gas station attendant who thought it might be counterfeit. This information led the authorities directly to Bruno Richard Hauptmann, who was later convicted and executed for the kidnapping and subsequent murder of the Lindberghs' son.

St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral, headquarters of the US/Mexican branch of the Russian Orthodox Church. Interior photos here.

Opened in 1991, this was the first structure in the city built as a mosque. The "spare, serene and deliberately modernist work" (see more photos) was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (architects of the Sears Tower, the new One World Trade Center, and Dubai's Burj Khalifa, which at over half a mile in height is by far the tallest building in the world) and was mostly financed by Kuwait, although many other Islamic countries provided support as well. In order to face the Kaaba, the mosque is oriented along the great circle route from Manhattan to Mecca (i.e., the shortest path on the surface of the globe between the two points), hence its 29-degree rotation off the street grid.

Mr. Codman, an architect and decorator who wrote The Decoration of Houses with Edith Wharton, designed this century-old French-style town house as a residence for himself. The Manhattan Country School has occupied the building since 1966, but is currently planning to sell it and move to a larger space.

This Madison Avenue facade is all that's left of the old armory, which was leveled in the 1960s to make way for a new school building (just visible at the far left) now occupied by Hunter College Elementary School and Hunter College High School. The original plan was to knock down the entire armory, but the city decided to protect the facade by designating it a landmark "just as the wreckers were about to demolish it." It now stands as "a dramatic backdrop for the school's playground" (photo).

This "sumptuous, Regency-style limestone house" was built in the early 1930s, its 55 rooms occupied by Mr. Loew, his wife, and 16 servants. Along with another massive residence erected on this block of East 93rd Street in the early years of the Great Depression, it was one of the last grand mansions constructed in Manhattan. In more recent years, it was home to the Smithers Alcoholism Treatment and Training Center before being purchased in 1999 by the private all-girls Spence School.

Sculpted cattle skulls are an unexpected sight on the frieze of this brick mansion, an "elegant amalgam of Federal and Georgian styling" (photo) constructed around 1917. The house, along with a ballroom addition to the west (photo) built around 1928, was purchased by the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia (ROCOR) in 1958 and continues to serve as the church's headquarters. ROCOR split off from the Russian Orthodox Church (whose US/Mexican headquarters we just saw a few blocks away) after the Russian Revolution, "when overseas exiles refused to accept the domestic church's subservience to the Soviet state", but the two churches re-established canonical communion in 2007.

from a glassy Harlem condo onto the frozen waters of the Harlem Meer

This minimum-security prison across 110th Street from Central Park has in recent years been home to Malcolm X assassin Thomas Hagan and disgraced former Tyco CEO Dennis Kozlowski (he of the $6,000 shower curtain and the vodka-urinating ice sculpture of Michelangelo's David).

Constructed in 1914, today's prison was originally the headquarters of the Young Women's Hebrew Association, serving as a dormitory and education center. (The roof, now caged, featured a garden in those days.) Presaging its current role as a place of involuntary confinement, the building saw later use as Army housing and as a school. In both cases, like today, it was surely filled with inmates dreaming of their eventual freedom.

on Lenox Avenue. In 1887, when this area west of Mount Morris Park was being developed, an article in The Record and Guide boasted of the local soil's "substratum of sand, which is the best possible safeguard against malaria".

Built in 1866 (the top floor was added later in the 19th century) for a maker of artificial limbs, this clapboard house was until recently owned by C.C. Dyer, an ex-wife of Geraldo Rivera. Interior photos here.

One of the city's more obscure memorials, this isolated little traffic island, accessible from the nearest sidewalk by jogging across an FDR Drive entrance ramp (Street View), is named for a Hungarian cavalry officer who fought for the Americans in the Revolutionary War.

This is the national headquarters of the ASPCA and the former home of Humility of Man Before A Group of Ageless Animals. Here's a close-up of the organization's seal, above, which depicts an angel intervening to keep a man from beating his horse.

Built in 1852-53, this is "one of the oldest of the few intact nineteenth-century wooden houses which remain in Manhattan north of Greenwich Village, [dating] from a period in which many of the houses on the outskirts of the city were of frame construction (prior to the implementation of an overall ban in Manhattan, due to fire hazards)." According to the AIA Guide to New York City, Eartha Kitt once called this place home.

Outside of Gracie Mansion, there are only four remaining wood-frame structures on the Upper East Side, and now we've passed by all of them today! No. 122, on the left, was built in 1859, and No. 120 was built in 1871.

Now home to the Jewish Museum, this is the 1908 Warburg mansion, one of the few survivors from a time when an "astonishing panoply of millionaires' mansions" lined the east side of Fifth Avenue, facing Central Park.

Well, to be more precise, the right half of the building is the 1908 Warburg mansion (photo). The almost identical left half, believe it or not, was constructed in the early 1990s as an addition to the museum. (As you can see, there is one visual giveaway that something's different about the left half: the newer limestone doesn't appear to be weathering so well. I've read that the ornamental features of the addition were carved from stone taken from the same quarry that was used for the original building, but I don't know if that applies to the rest of the new facade as well.)

This bronze bas-relief at the edge of Central Park, a replica of the original located on a Thames River promenade in London, memorializes William Thomas Stead, the British "Father of Tabloid Journalism", who lost his life on the Titanic.

An "unabashed sensationalist" and moral crusader, Stead was most famous for his lurid 1885 exposé of child prostitution in London, which he wrote to stoke societal outrage and prompt Parliament to pass a bill that would raise the age of consent for girls from 13 to 16. His campaign was quite successful in these regards, but it also landed him in prison after it was revealed that, as part of his investigation, he had arranged for the purchase of a 13-year-old girl from her parents and had her briefly sent to a brothel. While the girl was never actually prostituted, Stead twice had her examined to certify her virginity, which is to say she was effectively sexually assaulted twice. Although an extreme case, this incident shows how far the man was willing to go to get the story he wanted, in this instance a firsthand account of how easy it was to procure a young girl for prostitution. Of course, he declined to mention his personal role in the affair when he included the girl's tale in his exposé, calling her story "only one of those which are constantly occurring in those dread regions of subterranean vice in which sexual crime flourishes almost unchecked."

(In case you're counting, this is now the second Central Park monument we've seen honoring a man who had a controversial relationship with women's private parts. The first is located just twelve blocks north of here.)

In the 1890s, Stead became increasingly interested and involved in spiritualism. He published many works on supernatural matters, including a collection of "letters" he said were conveyed to him through automatic writing by a deceased acquaintance. Some believed he had foreseen his death on the Titanic in two fictional pieces he had written: an 1886 cautionary tale of the sinking of a trans-Atlantic steamer with an insufficient number of lifeboats — also like the Titanic, it had departed England for New York, and had made its final European stop at Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland — and an 1892 story that involves a ship striking an iceberg in the North Atlantic.

Stead also became an ardent advocate for peace in his later years; in fact, he was on his way to New York to deliver an address on the subject when he died on the Titanic. I found a satirical 1907 NY Times account of his tireless speechifying entitled "W.T. Stead, Inventor of the Continuous Speech, the Basis of Universal Peace". Here's an excerpt of an imagined transcript of his speeches:

Montreal, May 3.

[After briefly speaking about peace...]

If you want to hear the rest of this you must get berths on the train to Pittsburg. It is with great sorrow —

Pittsburg, May 3.

— that I have to inform you, ladies and gentlemen of Pittsburg, that I have only five minutes in which to take the fifteen minutes' ride to your depot. Pittsburgers, when coal is no longer being burned in this world, when steel is pointed out in museums as a relic of barbarism, when libraries are being torn down to make statues of Me and Peace, Pittsburg will be remembered as the city which provided the stage setting and gate receipts for my speech of to-day. Yes, sir, it will be remembered,

Buffalo, May 3.

— Buffalo will, as the city which provided a hall for the speech I spoke between Pittsburg and —

Milwaukee, May 3.

— Milwaukee. Ladies and gentlemen, the speech that made Milwaukee famous is about to eventuate. Beer and Peace go hand in hand. Nobody ever felt warlike after drinking beer. No, ladies and gentlemen. After dallying with the god Gambrinus, people are sleepy. Now, no nation is so peaceful as a nation asleep. Hence, when the history of the Universal Peace movement is written in deathless script, whatever that may be, the name of Milwaukee will be cited therein as being the city that drugged the gods of war, calmed the ferocious instincts of man, laid low the internal clamorings that bid us go out and kill something, and—and otherwise acted most sensibly and wisely. I am aware that that is a lame sentence, ladies and gentlemen, but you ought to hear some of my sentences. And I don't worry, anyhow. I care not who understands my speeches provided thousands hear them. Goodby. Send my luggage to Syracuse—I mean Cleveland.

This is one of the four sunken transverse roads that keep crosstown traffic mostly hidden as it moves through Central Park.