Xtreme Kutz

(This was originally Barberz #104, but I renumbered it to fill in the gap created when I downgraded the former Barberz #20.)

A guy who lives here told me they decorate the house for each Hindu holiday. He said the most recent one was about a week ago and involved bathing at the beach. Kartik Poornima?

Highland Place seems like a pretty straightforward name for a street that serves as a continuation of Highland Boulevard as it heads south from Highland Park and the high land of the Harbor Hill Moraine. But the way in which Highland Place acquired its rather boring name is actually quite interesting.

During and shortly after America's involvement in World War I, anti-German sentiment in the country reached a fever pitch, stoked by US government propaganda ("DESTROY THIS MAD BRUTE", for example). This hostility manifested itself in many ways, some violent and some simply ridiculous.

Sauerkraut consumption plummeted precipitously, "owing to the prejudice that had developed against the use of a food of such unmitigated German origin". In a move that recalls the freedom fries fiasco of 2003, a delegation of vegetable dealers petitioned the Federal Food Board in April of 1918 to change the name of sauerkraut to something like "liberty cabbage" or "pickled vegetable" in hopes of stimulating sales and preventing the "immense quantities" already produced from going to waste. The idea caught on in at least some quarters: I've found several grocery store newspaper ads from that era that mention liberty cabbage. The name must have been quite familiar to customers, because the ads don't even bother to explain that it's another term for sauerkraut.

(A couple of weeks after the war ended, American soldiers in Belgium discovered many tons of sauerkraut at an abandoned German supply depot. Along with the other food found there, the sauerkraut was taken by the Army and served to the troops for the next however-many-meals-it-takes-to-eat-that-much-liberty-cabbage. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle remarked: "At Arlon, Belgium, five carloads of sauerkraut were first converted into 'Liberty cabbage' and then converted into Liberty brawn and muscle without delay. Prejudices of the palate are easily overcome.")

Sauerkraut wasn't the only German-sounding thing to get a new wartime name. Hamburgers were rebranded "liberty steaks", frankfurters became "liberty dogs", and German measles were dubbed "liberty measles". When I read about that last one (in an article that also claimed that "liberty pup" was used as a euphemism for "dachshund" and that Cincinnati banned pretzels from the free lunch counters of its saloons), I couldn't believe it. It sounded like an absurd urban legend being passed off as a fact. It's one thing to try to remove any hint of your enemy from the stuff you like — food and pets, for example — but why would you replace "German" with "liberty" in the name of a disease?

Well, it turns out it isn't an urban legend at all. It apparently originated with some soldiers at Camp Dix in New Jersey who were stricken with German measles in early 1918. They were tired of being mocked for having such an unpatriotic-sounding illness, so they started a movement to change its name. The new name caught on to some extent at least: "Liberty Measles at West Point" was the NY Times headline when an outbreak occurred at the military academy shortly after the Camp Dix story ran. I even found a fairly technical article published in the March 1920 bulletin of the NYC Department of Health that refers to the disease solely by the patriotic version of its name, with sentences like: "It serves to differentiate the beginning of measles rash from other rubeoliform eruptions—Liberty measles, variola, antitoxin rashes, vaccination rashes, drug eruptions, multiform erythema and similar eruptions."

NYC joined in on the fun by renaming a few streets that, "to the offense and humiliation of our citizens", bore German-inspired (or Austrian-inspired) appellations. In the Bronx, German Place became Hegney Place, named for Arthur Vincent Hegney, the first Bronx soldier to die in the war. In Brooklyn, Bremen Street became Stanwix Street, Vienna Avenue became Lorraine Avenue (which no longer exists; it was partially incorporated into Linden Boulevard, with other sections becoming Dewitt Avenue and Loring Avenue), Hamburg Avenue became Wilson Avenue, presumably named for Woodrow Wilson, the sitting president at the time (a rare instance of a street being named for a living person), and — finally getting back to the starting point of this whole discussion — Dresden Street became Highland Place.

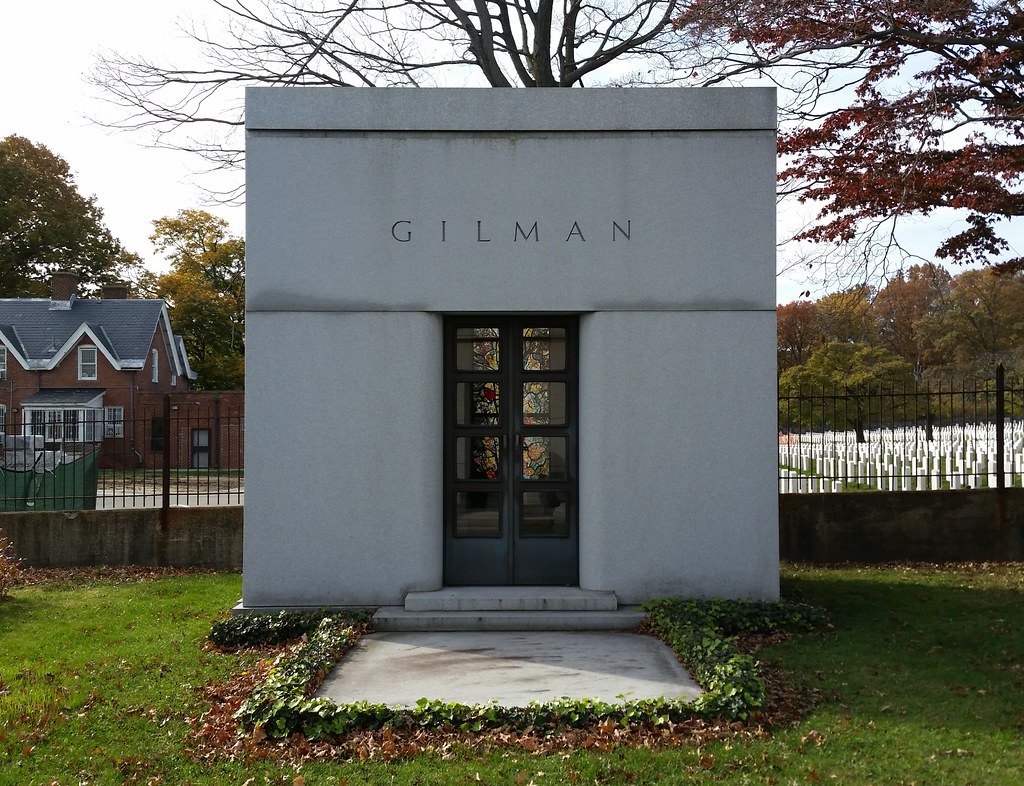

Cypress Hills National Cemetery, the only national cemetery in the five boroughs, was one of the 14 original national cemeteries established in 1862 in response to the mounting death toll of the Civil War. (There were no Civil War battles fought in New York, but there were plenty of soldiers dying in the area's military hospitals.) The oldest section of the cemetery is actually located inside a nearby private cemetery named, confusingly, Cypress Hills Cemetery. The main section, above, was purchased by the federal government in 1884. And a very small third section, also located inside Cypress Hills Cemetery, was added in 1941.

The muffled drum's sad roll has beat

The soldier's last tattoo;

No more on life's parade shall meet

That brave and fallen few.

On Fame's eternal camping-ground

Their silent tents are spread,

And Glory guards, with solemn round,

The bivouac of the dead.

That's the first stanza of Bivouac of the Dead (full text), an elegy written by Theodore O'Hara in remembrance of his fellow Kentuckians who died at the Battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican-American War. O'Hara later served as a Confederate colonel in the Civil War, but his poem resonated with veterans from both sides of the conflict and became a popular expression of loss in both the North and the South. Today, its verses can be found in national cemeteries all over the country, including here at Cypress Hills National Cemetery. (Another plaque near the entrance contains the first half of the first stanza.)

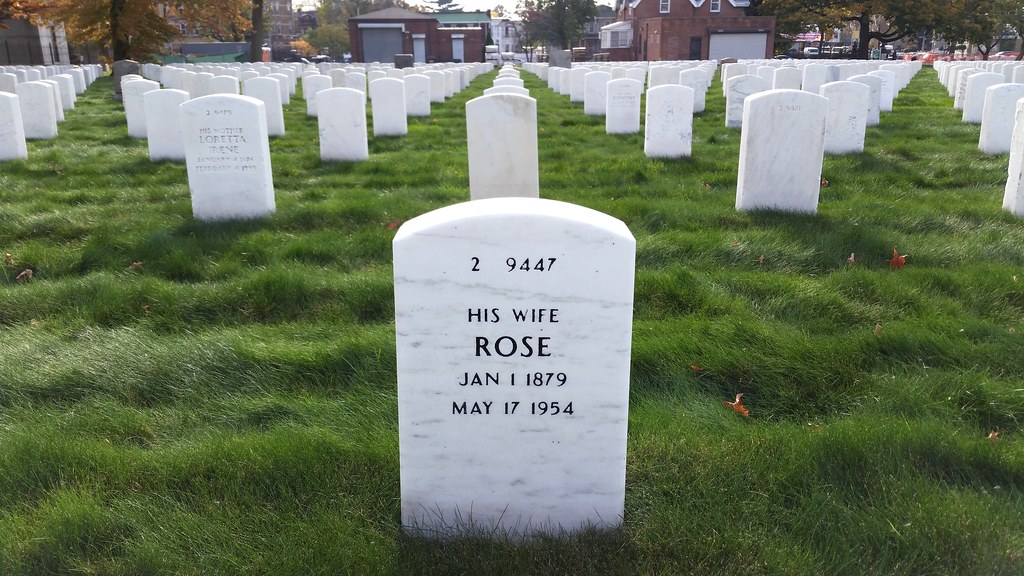

Here at Cypress Hills National Cemetery, you can occasionally spot the name of a military wife/mother on the back of the gravestone of her husband/son. I wasn't paying particularly close attention to such things, but I also noticed, in the officers' sections, several instances of a wife getting her own stone.

Notorious gangster/war hero.

Here's a colorful story about Lovett's wife Anna and the men in her life. Long story short: her mom shot and killed her dad, Wild Bill was murdered a few months after they wed, her one-legged gangster brother was killed a couple of years later, and then she married another gangster who was shot to death a few years after that. The deaths of her husband, brother, and husband represented the downfall and final collapse of the White Hand gang, the last Irish-American street gang to control the northern Brooklyn waterfront.

This cross is dedicated to the 25 French sailors who died while on duty in American waters during the flu pandemic in the fall of 1918 around the end of World War I. 22 of the sailors are buried here; the bodies of the other three were returned to France.

The enormous mausoleums of neighboring Salem Fields Cemetery stand in stark contrast to the uniform rows of modest headstones here at Cypress Hills National Cemetery.

It came right up to me and then jumped the fence into Salem Fields Cemetery.

An officers' section of Cypress Hills National Cemetery and a line of mausoleums in Salem Fields Cemetery

There have only been 19 two-time recipients of the Medal of Honor (the country's highest military honor), and three of them are buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery: Daniel Daly ("Come on, you sons of bitches, do you want to live forever?"), John Cooper, and Louis Williams (a.k.a. Ludwig Andreas Olsen).

Salem Fields Cemetery, along with neighboring Cypress Hills National Cemetery, belongs to a huge cluster of 17 contiguous cemeteries located along the middle of the border between Brooklyn and Queens.

Lip Pike was the first Jewish baseball star. He led the National Association (the first professional baseball league and the predecessor of the National League) in home runs in its first three seasons, 1871-73.

Austrian-born Joseph B. Greenhut was the second man in Chicago to enlist for service in the Civil War following President Lincoln's call for volunteers in 1861, and he rose to the rank of captain before resigning his commission in 1864. He became quite wealthy after the war, establishing the world's largest distillery in Peoria, Illinois (the "Whiskey Capital of the World") and later acquiring control of a major department store company in Manhattan. A 1912 history of Peoria attributed his success in business to his "marked ability to coordinate interests and to combine seemingly diverse factions into a harmonious whole. It is said that difficulties vanish before him as mist before the morning sun." In 1909, he purchased Shadow Lawn, a magnificent New Jersey estate (photos) that was used by President Wilson as his Summer White House (video) for the last two months of his 1916 re-election campaign.

Here in mausoleum-packed Salem Fields Cemetery, cut off from the free-ranging air currents that afforded swift passage across the wide-open plains of Cypress Hills National Cemetery, our itinerant balloon friend has become rather sluggish.

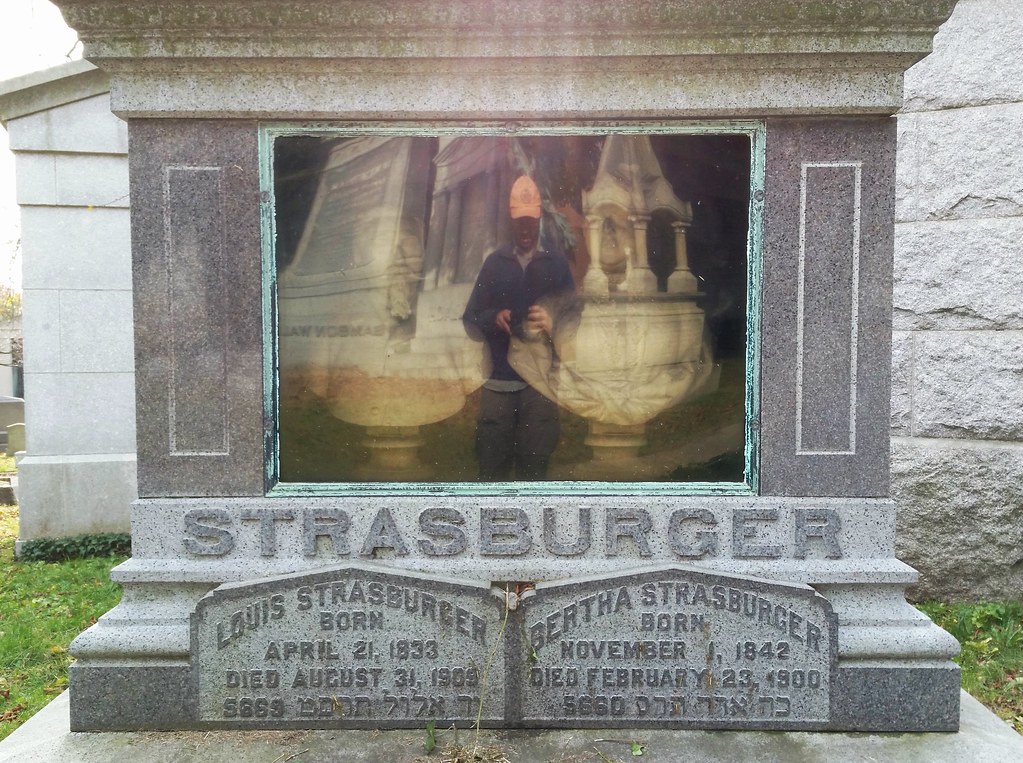

It's tough to see with the reflection, but here's a closer look at the encased busts of Louis and Bertha.

In 1847, Meyer Guggenheim was a 19-year-old immigrant peddler fresh off the boat from Switzerland. By the time he died in 1905, he had become the head of one of the wealthiest families in the United States, having built an enormously profitable mining and smelting empire that he passed down to his sons. (His facial hair, while not quite in the same league as Peter Cooper's or Henry MacCracken's, also deserves a mention here.) His descendants later turned to philanthropy and became prominent patrons of the arts and sciences, the famous spiraling Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue being just one of the many outlets for their fortune.

The family's mausoleum here in Salem Fields Cemetery is often compared to the ancient Tower of the Winds in Athens, but a cursory visual comparison of the six-sided mausoleum and the eight-sided tower reveals that they have very little in common other than a similar general shape.

Bob Marshall was a dedicated wilderness advocate whom we first learned about back in Montana, where a sign hanging outside his namesake preserve tells of his famous answer to the question of how much wilderness America really needs: "How many Brahms symphonies do we need?"

Among New York City's many grand cemeteries, Salem Fields is not particularly well known. But its western section is positively lousy with mausoleums — jam-packed to a degree I've never seen before.

At left, the tomb of Benjamin Altman, founder of the B. Altman & Co. department store and the charitable Altman Foundation, is reportedly a simplified version of the Alexander Sarcophagus (not to be confused with the tomb of Alexander the Great, despite what the previously linked article says).

This oddball artwork can be found on the wall (or, rather, is part of the wall) of Brooklyn's PS 7. Here's a look at the left side of it.

This block-long street and its neighbor to the north, Adler Place (originally called Adelphi Place), were built on the former site of Adelphi Oval, which existed from about 1907 to 1916 as the athletic field of the Adelphi Academy and Adelphi College.

Rick Gomes of the East New York Project believes that this house at 107 Pine Street was built between 1886 and 1893, but that its columns were added at a later date, sometime before 1918, possibly by a carpenter who purchased the house in 1904. He also notes that there's a similarly unimposing house with almost identical columns tacked onto it located just over half a mile from here at 81 Essex Street.

Just across the street from 107 Pine is the old social/worship hall of Blessed Sacrament Parish, built in 1911-12. I wonder if the construction of its impressive columns had any influence on the aforementioned carpenter, or if his columns were already standing then.

In the background at right, you can see a J train on the Jamaica Line.

Built 1924-26. Until he got kicked out in sixth grade, Tony Danza was a student at the parish's school across the street, supposedly hitching a ride to class each day on the back of his dad's garbage truck.

The z-in-lieu-of-an-s has to be in the barbershop's name to officially count.

Blue Ridge Farms, whose former processing plant occupies this entire block in Cypress Hills, was once the East Coast's largest producer of prepared salads, and by the 1990s was Brooklyn's third-largest manufacturer (behind Pfizer, which closed its Brooklyn plant in 2008, and Cascade Laundry, which went out of business in 2010). The company had been run by the Siegel family ever since its founding in the mid-20th century, but in 2004, facing some financial difficulties, the Siegels agreed to take on Thomas Kontogiannis as a major investor, which led to a series of shady dealings with him that eventually resulted in his family taking control of the company and selling off all its assets, including its name. (Kontogiannis is currently serving time in federal prison, having been sentenced twice in recent years: in 2008 for laundering bribes for former Representative Randy "Duke" Cunningham, and in 2011 for orchestrating an enormous $98 million mortgage fraud.)

After the demise of Blue Ridge Farms, the company's production complex here in Cypress Hills was left vacant, and was the site of a huge seven-alarm fire in 2012. The burned-out factory is still standing today, a massive, forlorn monument to the downfall of a once-thriving business.

Currently home to Achievement First East New York Middle School (PS 65 is now located in a new building nearby), this school (old photos) dates back to 1870, but most of the structure, including the part you see above, was built during a major expansion in 1889.

from A. Charles, King of New York. Looks like I just missed seeing his house decked out for Halloween.

The door of the truck says "IRON", so I'd guess that the MTA's Elevated Iron Fabrication team is doing some work here on the elevated structure of the Jamaica Line (J and Z trains).

This section of the Jamaica Line between the Alabama Avenue and Cypress Hills stations was originally used by the old Lexington Avenue and Broadway Els, and is said to be the oldest elevated structure in the subway system. The part that runs between Alabama and Schenck Avenues opened in 1885, and the rest of it, including what you see above, opened in 1893.

According to Forgotten New York, a little diagonal beam found on the elevated structure here (mostly obscured from view above, but clearly visible here) is the last remnant of an old connection to the Atlantic Branch of the Long Island Rail Road that was in service from about 1898 to 1917, cutting through the block now occupied by the old Blue Ridge Farms processing plant.

For much of the 1990s, this vacant lot was the subject of a dispute between Blue Ridge Farms, whose former processing plant (visible in the background) is located right across the street, and the city and state governments. The city acquired the land from its previous owner in 1992 through eminent domain with the intent of building a new school to relieve the extreme overcrowding at IS 171, which at the time was sharing its building with PS 7. Blue Ridge, however, wanted the lot for an expansion of its facilities, and threatened to leave New York if it couldn't have it.

The city and state worked out an agreement with Blue Ridge that would allow the company to obtain the desired land in exchange for a slightly larger property it owned next door. Before the swap could move forward, however, a new mayor (Giuliani) and governor (Pataki) were elected, and Pataki decided to block the deal. Finally, in 1997, Giuliani announced that the lot would be turned over to Blue Ridge after all and that a new PS 7 would be built on a different site in the neighborhood. As we've seen, PS 7 did eventually get its new school, but Blue Ridge never built its expansion, and the much-contested lot, still owned by the city, has remained empty to this day.

This place opened during the latter part of Obama's first term, sometime between August 2011 and May 2012. I wonder if its name is an allusion to his acknowledged weakness for cigarettes.

According to a 1904 NY Times article entitled "Shaft for Jewish Soldiers", this monument in Salem Fields Cemetery is "at least one of the first, if not the first, to be erected to the memory of the Jewish soldier who gave his life for the preservation of the Union." The plaque at the base of the obelisk reads: "To the memory of the soldiers of the Hebrew faith, who responded to the call of their country and gave their lives for it's [sic] salvation during the dark days of it's [sic] need, so that the nation might live."

Perhaps this block embedded in the sidewalk outside Cypress Hills National Cemetery was meant to identify the cemetery as federal property.

The greatest street name in the city! (Sorry, Featherbed Lane.)

During the latter part of the 19th century and into the 20th, most of Brooklyn's drinking water came from farther east on Long Island. It was carried toward Brooklyn through an underground aqueduct and was then pumped up to the Ridgewood Reservoir. The water's path to the reservoir can be easily deduced by looking at a map, thanks to a couple of fitting street names: Conduit Avenue/Boulevard follows the path of the aqueduct, and Force Tube Avenue traces the route of the pipes through which the water was pumped up to the reservoir.

As it happens, the original pumping station (1924 aerial view) near the foot of Force Tube Avenue stood on the now-vacant lot that was so highly coveted by Blue Ridge Farms in the 1990s, as well as on the adjacent property that Blue Ridge was willing to exchange for that lot.

This is the second establishment we've seen today named for our current (and 44th) president. It's been in business since sometime between August 2011 and September 2013.

One of a few odd scenes painted on the wall of this C-Town grocery store

The strangest of the aforementioned C-Town murals

Here's some info about this house, as well as some old photos of it. And here's a little historical tour of this stretch of Arlington Avenue, supposedly once known as "Doctors' Row".

Incidentally, I learned that Arlington Avenue is named for the famous Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia. That might seem like an odd source of a name for a street in Brooklyn, but a glance at the map reveals that the eastern end of Arlington Avenue lies just three blocks away from Cypress Hills National Cemetery.

Constructed in 1895, PS 108 (old photos) was designed by James W. Naughton, who was the architect of more than 100 schools during his tenure as Brooklyn's superintendent of school buildings from 1879 to 1898. We've already seen another of his designs today: the 1889 expansion of the former PS 65.

PS 108's secondary name, the Sal Abbracciamento School, honors a longtime neighborhood resident who successfully led the fight to save both PS 108 and PS 65 from demolition in the 1960s.

Starting in the 1850s, to meet the needs of its rapidly growing population, the then-independent city of Brooklyn constructed the Ridgewood Reservoir (old photos) just over the county line in Queens, atop the Harbor Hill Moraine in what is now Highland Park, and built an aqueduct system to supply it with water from a series of dammed streams and wells located farther east on Long Island, in today's Queens and Nassau Counties. (As we recently learned, the water flowed west through the eponymous conduits of Conduit Avenue/Boulevard and was pumped up to the reservoir through the eponymous force tubes of Force Tube Avenue.) Over time, more water sources were incorporated into the system, and the reservoir grew as well: a third basin was completed in 1891, doubling the total capacity to some 300 million gallons.

Brooklyn became part of New York City in 1898. With the development of the city's two vast Catskill Mountain aqueduct systems (the Catskill and Delaware Aqueducts) in the early and mid-1900s, the Long Island water supply became less and less important. The water from the Catskills, in addition to being much more plentiful, was also cheaper to transport: unlike the Long Island water, which required pumping, it originated at a high enough elevation to reach the city under the force of gravity alone. Thus, the Long Island water was used only when the city's demand exceeded the capacity of its gravity-powered upstate aqueducts (the Catskill systems plus the older Croton and Bronx/Byram systems). The Ridgewood Reservoir, while maintaining its connection to the Long Island supply, also began receiving Catskill water. It continued to function as a distributing reservoir until about 1959, after which it was used only as a backup supply. It was finally taken out of service altogether sometime around 1985 or 1989.

Over the years, the reservoir's three basins, covering some 50 acres, have been slowly reclaimed by nature.* The center basin, above, contains a pond surrounded by phragmites, the invasive, ubiquitous reed found in wetlands all over the city. The east and west basins, on the other hand, are "filled and completely vegetated", and are home to "closed forest, scrub, woodland, and vineland" habitats, according to the Parks Department. For more specifics, check out this detailed survey of plant life in the reservoir.

In 2007, it came out that the Parks Department was leaning toward leveling the forest in the largest (west) basin and building new athletic fields there. This caused an uproar among environmentalists and many local residents, who argued that the reservoir's wildness is a precious resource that needs to be preserved and that Parks should renovate the existing ball fields in the adjacent areas of Highland Park instead of building new ones inside the reservoir. After taking a tour of the reservoir in 2008 and seeing its charms firsthand, Bill Thompson, then the city's comptroller, co-authored an NY Times op-ed arguing against the destruction of the forest, and, a month later, rejected a Parks Department contract to build athletic fields in the basin.

In 2009, Thompson approved a contract to fix up the walking paths and other perimeter features at the reservoir, work that was completed in October 2013. The contract also specified that three conceptual plans for the overall development of the reservoir, including one design for passive recreation, would have to be created and submitted to the public for feedback before the project could go ahead. Although there's currently no funding lined up for future work at the reservoir, the three designs were presented to the public in June 2013. To describe them briefly: one would allow access only to the west basin, where walking trails would be built; one would provide for light recreation in each basin; and one would involve the additional construction of baseball fields, a comfort station, and a "waterworks-themed adventure playground" in the west basin.

Just this past summer, it looked like the reservoir was facing another threat from the Parks Department. Parks officials were talking about starting work by August on a $6 million project that would involve breaching the inner and outer walls of the reservoir in order to install culverts. Additionally, a gravel roadway would be built between the three culverts for construction and maintenance vehicles to use. The purpose of this work was to bring the reservoir into compliance with State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) regulations (although some suspected that Parks might be going through with the project as a sly way to lay the groundwork for future development of the reservoir). Basically, the DEC has classified the reservoir as a Class "C" or "High Hazard" dam. The city obviously doesn't want to have to maintain a defunct reservoir as if it were an active dam, so it needs to get the reservoir reclassified as a Class "A"/"Low Hazard" or Class "D"/"Negligible or No Hazard" dam. The culverts would lower the hazard level by allowing any water that gathers in the reservoir to flow out before it reaches a potentially dangerous volume.

Of course, a much simpler way to get the reservoir reclassified would be to ask the DEC to change its classification. But would that be appropriate in this case? Well, the state defines a high hazard dam as a dam whose failure "may result in widespread or serious damage to home(s); damage to main highways, industrial or commercial buildings, railroads, and/or important utilities, including water supply, sewage treatment, fuel, power, cable or telephone infrastructure; or substantial environmental damage; such that the loss of human life or widespread substantial economic loss is likely."

If that strikes you as a ridiculous description of a mostly empty reservoir, you're not alone. But it was only after community members and elected officials raised a ruckus that Parks decided to hold off on the culvert plan and apply to the DEC for reclassification instead. As far as I know, nothing's been approved yet, but the DEC commissioner seemed amenable to the idea in a letter to the aforementioned elected officials.

* It's difficult to tell when each of the basins was abandoned. In my research, I repeatedly came across the claim that only one of the three basins was used during the reservoir's final, post-1959 role as a backup supply, but this is clearly contradicted by some historical aerial photos I found using the USGS's EarthExplorer. Judging from what I see in the photos, the center and west basins were both kept full until at least 1976. By 1984, the west basin looks to have been abandoned and to have started its transition to a more natural state. The center basin still appears to be in use in 1985, but the phragmites invasion was underway by 1994. It looks like the east basin hasn't been used since at least 1959, and so presumably started growing wild much earlier than the other two basins. Just for the sake of thoroughness, and to put everything in one place, here are the relevant aerial photos I was looking at:

- February 18, 1954: All three basins are full.

- October 30, 1959: From this point on, the east basin looks abandoned in every photo. It contains water at times, but is never full.

- April 29, 1960

- May 5, 1960

- February 23, 1966

- September 15, 1969

- September 23, 1972

- August 30, 1976

- October 29, 1976

- March 26, 1984: The west basin now appears abandoned.

- March 16, 1985

- April 4, 1994: Phragmites can be seen in the center basin. This is the earliest photo I can find in which all three basins are abandoned.

If you're still reading this, you might also be interested in viewing the city's high-resolution aerial images of the reservoir over the years: 1924, 1951, 1996, 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012.

of the Ridgewood Reservoir. Here's the description of this section of the basin from a 2005 Parks Department survey of the reservoir:

Black locust and mugwort dominate throughout this area. Other species found are: buckthorn, Phragmites, goldenrod, bush honeysuckle, bigtooth aspen, grey birch, quaking aspen, Royal Paulownia, Japanese knotweed, white snakeroot, smartweed, poison ivy, bittersweet nightshade, oriental bittersweet, and cottonwood. A great deal of bird activity was observed in this unit.

Located at the northern end of the Ridgewood Reservoir, between the two original basins that went into operation in 1858, this building stands atop the sluice gates that controlled the amount of water leaving those basins. The water would pass through the sluices into an effluent chamber, where it would enter the pipes of the distribution system and be carried down to the people of Brooklyn.

From Brooklyn Water Works and Sewers: A Descriptive Memoir, written by the chief engineer in charge of the reservoir's construction:

The water space of the effluent chamber is connected by passages eleven feet wide, with the two divisions of the reservoir. A heavy granite wall is built across each passage, rising to the same level as the top of the reservoir banks. In each wall there are four openings, the two lower openings being 3x3 each, and the two upper openings 3x4 each. Iron sluices running in iron slides, faced with composition metal, cover and control these openings. From these sluices, iron rods of two inches diameter rise to the top of the work, where they terminate in screws and gearing for the movement of these sluices. [Two hand-wheels for controlling the sluice gates can still be found behind the gatehouse.] . . .

In front of the sluices, towards the reservoir, in each passage, copper wire screens are placed, twenty-two feet in height, to prevent fish, leaves, &c., from passing into the effluent chamber, and so into the supply pipes. . . .

The apparatus for moving the sluices is protected by a small house built over each passage.

Three Obama-inspired business names in one day? (Here are the other two.) Prior to today, during the entire course of this walking project, I had only come across three other establishments named for our current president. (I previously said I had only come across two, but I had forgotten about the most explicit one of all.) Obama Deli & Grill had already either been renamed or gone out of business when I passed by. Obama Fried Chicken has gone out of business since I passed by. And Barack Hussein Obama Children Center, it seems*, may never have gone into business in the first place (although its awning was still up when the Street View car drove by in October). So it's entirely possible that most or even all of the active businesses in the city named for the president are located here in Cypress Hills, on or just off of Fulton Street, within seven blocks of each other. Weird!

(FYI, King Barack opened up shop sometime between August 2011 and September 2013.)

* The NY Post article linked above makes Sheikh Moussa Drammeh ("Sheikh" is his first name, not a title, and is misspelled in that article), a Bronx imam, sound like a sleazeball and/or nutcase.** But from what I've read, he's a well-respected, positive force in his community of Parkchester. In fact, the Post itself honored him with one of its annual Liberty Medals back in 2007. He founded the Islamic Leadership School — the Bronx's only Islamic school — which, in a bizarre coincidence, opened on September 11, 2001. His latest community venture is a neighborhood "peace patrol" that aims to help troubled kids before they turn to crime.

He's also twice been in the news for his generosity to other religious organizations. In 2004, when the Interfaith Center of New York, led by a former dean of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, was unable to make rent on the Midtown Manhattan space it had called home for five years, Mr. Drammeh gave the group office space in the Bronx free of charge, in the same building that's now home to, among other things, his mosque, his school, and the apparently never-opened Barack Hussein Obama Children Center.

In 2008, when a tiny, aging Jewish congregation in the neighborhood found itself without a home, Mr. Drammeh offered up space in his mosque, rent-free, saying "I’m paying back. I am an immigrant, from Africa. I came here to New York and all the religious freedoms and acceptance, I don’t have to fight for it, the Catholic and Jewish communities already fought, and now it’s for my behalf. It would be very ungrateful if I don’t play any role, especially for the older folk, so they can benefit in turn from my being here. It is my time to say, let me [pay back] at least a little bit for the neighborhood you made and the work you have done." As far as I can tell, the congregation is still in existence and is still meeting in the mosque.

There's also a pedestrian aspect to this story. When the congregation was on the brink of collapse, shortly before Mr. Drammeh's offer, it was taken over by young Chabad rabbis and rabbinical students who had responded to the elderly Jews' requests for help. Forbidden from traveling by motorized vehicle or bicycle on the Sabbath, the Chabadniks began regularly walking the 15 miles from their homes in Crown Heights, Brooklyn to the mosque on Saturday mornings to lead services. (Nerd note: the route mentioned in the article is over 16 miles long.)

** I should note that the Post was correct about Mr. Drammeh inventing what it called a bathroom-sink alarm. In 2013, he was issued US Patent No: 8,344,893 for a "hygienic assurance system" that uses a "plurality of sensors" and a "plurality of visual and audible signals", as well as a camera, to remind people (presumably employees) to wash their hands after using the toilet and to ensure that those who don't wash up properly, "for an adequate time span", can be identified "for later reprimanding . . . by the facilities owner or hygiene enforcer." But I have some good news for those of you who hate washing your hands. I've looked over the patent and found a loophole. Flushing is the action that triggers the system into thinking you need to wash up, so all you have to do is not flush!

at the Church of St. Sylvester. Check it out in the daylight.

This little parklet looks much more welcoming than the last such Place we saw. Apparently, there was originally a bronze eagle on the World War II memorial above. It must have been either stolen or damaged, but I'm guessing those are its talons still perched atop the monument.

(The wildly imaginative name of this public place brings to mind the string of Parks found along the Prospect Expressway.)